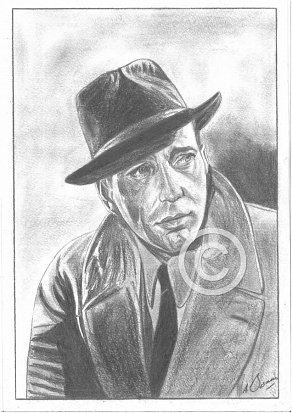

Humphrey Bogart

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

The Petrified Forest (1936)

Released in 1936, Bogart’s portrayal of the gangster Duke Mantee would establish him as a major cinematic lead and pave the wave for his halcyon period in the 40’s and early 50’s.

Leslie Howard played Alan Squier, a disillusioned intellectual and once-great writer who wanders into a café near Arizona’s Petrified Forest. There he meets Gabby (played by Bette Davis), a young women who longs to move to France and become an artist. The peaceful ambience is interrupted by the arrival of Duke Mantee and his thugs, who are on the run from the police.

In keeping with its origins as a theatrical stage play, ‘The Petrified Forest’ remains essentially a claustrophobic character study, Bogart exuding a quiet reflectiveness, despite his obviously gruff and controlling exterior. He refrains from killing anybody unnecessarily, an acknowledgement perhaps, to the inevitability of his own impending demise.

Edward G. Robinson was originally slated to play the role of Duke Mantee, but star Leslie Howard insisted on Bogart. The studio was disapproving, perceiving the actor as a solid B-Movie lead and supporting player, not a star. Howard stuck to his guns, eventually winning the executives over. Bogart was forever grateful to Howard for his unswerving support and on August 23, 1952, named his newborn daughter Leslie Howard Bogart in honor of his late friend.

Bogie subsequently reprised his role of Duke Mantee in the live “Producer’s Showcase” telecast, broadcast on May 30, 1955. The original play by Robert Sherwood, had provided the actor with his first taste of stardom, his stage persona electrifying Broadway, yet this last reprise stumbles and stutters. Bogart is ponderous, seemingly immobile, his enervated performance betraying the earliest signs of the cancer that would claim him eighteen months later and Bacall is way too old at thirty one, to be convincing as the restaurenteur’s daughter.

Banking $50,000, the highest television fee given to an actor for a single performance on the small screen, the production also showcases Henry Fonda in the role of the intellectual who challenges Duke Mantee during the hostage crisis. Director Delbert Mann shoots Bogie primarily in close-up, adding much to the immediacy of his growling delivery yet there’s little hint of menace to lift this underwhelming affair.

Orinally filmed in colour, the telecast survives today as a medium grade monochrome 16mm kinescope, courtesy of Lauren Bacall, who retrieved the only known surviving copy from her own private archive. Circulating quietly for years as a bootleg video, the production nevertheless offers Bogart fans a rare glimpse of the mighty performer at the twilight of his career and remains significant as the last Bogart-Bacall teaming.

The surviving television copy can be viewed on Youtube via

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=riylfh_9ir8

the superior film version remaining widely available as an apt reminder of his then burgeoning screen persona.

High Sierra (1941)

Thanks in no small part to some well intentioned but crucially misjudged casting decisions by George Raft’s agent, Bogart would acquire three prime ‘second choice’ roles in ‘The Maltese Falcon’, ‘Casablanca’ and this Raoul Walsh directed epic.

Breaking the mould of 30’s villainery, Bogie’s firing on all cylinders in a new decade with a three dimensional character coming to the realisation that he must continue with a life in crime. As Roy ‘Mad Dog’ Earle, he takes on an offer to crew chief a heist at an expensive resort hotel in Nevada. Unable to cherrypick the men he’d like, and with the added complication of one Ida Lupino leaving two of them in hormone overdrive, the portents aren’t good.

Unsurprisingly, the heist is botched leaving Roy to hole up overnight in the Sierra mountains before the inevitable shootout with the police.

The Maltese Falcon (1941)

Adapting Dashiell Hammett’s novel, ‘The Maltese Falcon’, and rendering the film as close to the original story as the Production Code allowed, rookie director John Huston created what is often considered the first film noir. In his star-making performance as Sam Spade, Humphrey Bogart embodies the ruthless private investigator who accepts the dark side of life with no regrets. One night, a beguiling woman named Miss Wanderly (Mary astor) walks into the office and by the time she leaves, two people are dead. Miss Wanderly appeals for Sam’s protection and throughout the movie murder after murder occurs over the lust for the statue of the Maltese Falcon.

The Wanderly character is a classic femme fatale, using sex to save her skin yet she overestimates Spade’s malleability.

‘Well, if you get a good break, you’ll be out of Tehachapi in twenty years and you can come back to me then. I hope they don’t hang you, precious, by that sweet neck’.

‘You’re not’ she intones with horror.

‘Yes, angel, I’m gonna send you over. The chances are you’ll get off with life. If you’re a good girl, you’ll be out in twenty years. I’ll be waiting for you. If they hang you, I’ll always remember you’.

Convincing herself that he’s jesting, she extols the vitues of his offbeat personality yet when the reality of her predicament becomes all too apparent, she rounds on him;

‘You’ve been playing with me – just pretending you cared to trap me like this. You didn’t care at all! You don’t love me!

Firm in his conviction, he answers;

‘I won’t play the sap for you!’

‘You know it’s not like that!’ she responds.

‘You never played square with me since I’ve known you!’

‘You know in your heart that in spite of anything I’ve done, I love you’.

‘I don’t care who loves who! I won’t play the sap!’

The Maltese Falcon was nominated for three Oscars including Best Picture and Best Screenplay, establishing Huston as a formidable double talent and Bogart as the archetypal detective antihero.

Across the Pacific (1942)

Bogart is Rick Leland, a cashiered Army man seemingly ostracised from his homeland, yet in reality a covert operative in Army Intelligence. On board the Japanese N. Y. K. freighter bound south from Canada to the Canal zone, he encounters a motley crew including Dr Lorenz (Sidney Greenstreet), a college professor and Japanese spy, Alberta Marlow (Mary Astor) and Joe Totsuiko (Victor Sen Jung), a bespectacled judo student who initially appears friendly enough – his “Allo Lick” greeting injecting humour into the proceedings as the protagonists become acquainted. Alberta’s motives remain ambiguous, but her compromised position is revealed as the film builds towards its climactic end.

Thwarting a dastardly Japanese plot to destroy the Panama Canal, Bogart moves at a sprightly pace. Whether flirting with Alberta, sparring with Joe, or discussing eastern culture with Lorenz, he’s undoubtedly the star attraction; that malevolent sneer of his conveying an inherent mistrust for all on-board.

Last minute script revisions were required when the Japanese actually bombed Pearl Harbour (the original target), and the final scenes are compromised by below par special effects. Director John Huston’s Signal Corps commission would shanghai him from the final weeks of filming, and his absence is palpable. Nevertheless, it’s a lively espionage drama, and a well timed cinematic release as America emerged from a concerted period of neutrality.

Casablanca (1942)

One of the most beloved American films, Casablanca is a captivating wartime drama of adventurous intrigue and romance starring Humphrey Bogart, Ingrid Bergman and Paul Henreid. Set in Morocco during World War II, Bogart is a cynical American expatriate living in Casablanca. He owns and runs the most popular nightspot in town “Rick’s Café Américain”, an upscale nightclub that has become a haven for refugees looking to purchase illicit letters of transit which will allow them to escape to America.

When Rick’s former lover, who deserted him when the Nazis invaded Paris, Ilsa (Ingrid Bergman), surfaces in Casablanca with her Resistance leader husband, Victor Laszlo (Paul Henreid), Rick is pulled into both a love triangle and a web of political intrigue. Ilsa and Victor need to escape from Casablanca, and Rick may be the only one who can help them.

Even today, for 102 minutes, I can park my cynicism and believe once again in romance and nobility, sentiments no more finely imbued than in the character of Rick.

The Two Mrs Carolls (1947)

Alienating both Barbra Stanwyck and the Milk Marketing Board, Humphrey Bogart plays artist Geoffrey Carroll, a psychotic serial killer disposing of his wives through the slow ingestion of poison. His ‘Angel of Death’ portrait is not an avenue I shall be pursuing myself, but works effectively here in establishing the leading character’s mental state. The slightly dishevelled hair, the hint of dissipation around the eyes, a barely concealed skeletal frame beneath a one piece black leather outfit, these are features unassociated with a rapturously received present, unless of course, the female client is a Goth. I may surprise myself yet!

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ChFysLtfKAc

Dark Passage (1947)

The treasure of Sierra Madre (1947)

Key Largo (1948)

The African Queen (1951)

Directed by John Huston on location in the Belgian Congo and the British protectorate of Uganda) the film was nominated for four Academy Awards – Best Actress (Katharine Hepburn), Best Screenplay (James Agee and John Huston), Best Director, and Best Actor (Humphrey Bogart). Overlooked three years earlier by the Academy for his superb work on ‘The Treasure of the Sierra Madre’, Bogart took home the elusive statuette with a highly popular win.

Whether troubled by his rumbling intestines or blood sucking leeches, here is a man at the top of his game. The interplay with Hepburn is a joy to behold, Bogart´s growing feelings for the spinster pushed to the limit as her logical but seemingly impractical demands wear him down into grudging submission. Responding to her battle cry with a makeshift torpedo, Charlie Allnut is clearly a man on a mission of love and war.

The Caine Mutiny (1953)

“I’m a book man. I believe everything in it was put in for a purpose. On this ship, we do things by the book. Deviate from the book you better have several good reasons for it but let me remind you, you’ll still get an argument from me. And I don’t lose arguments on my ship. That’s why it’s nice to be captain. Aboard my ship, excellent performance is standard, standard performance is substandard and sub-standard performance is not permitted to exist”

Bogart’s tour de force, his portrayal of the crumbling captain Queeg, essentially the perfect encapsulation of all he had learned over a quarter of a century to hone his acting skills, remains to this day, an unceasing visual delight. In a memorable performance on the witness stand, Queeg gradually traps himself and loses all credibility during his own testimony. He slowly disintegrates, becomes incoherent and paranoid, and discredits himself under tough cross-examination questioning from Greenwald, (José Ferrer) about each incident. Queeg foolishly and hysterically defends and justifies his actions in the strawberries incident, and condemns the disloyalty of his officers, whilst all the time, there are those two steel balls, gently rolling in the palm of his hand. Babbling on absent mindedly, the courtroom is witness to his mental disintegration, a previously unblemisheed career sabotaged by self serving and manipulable officers.

Amongst the sterling support cast is Fred MacMurray as Thomas Keefer, a lowlife duplicitous character of the type I have periodically met all my life. He’s not even standing trial, having coerced and manipulated his colleagues into undermining Queeg’s authority.

Admitting to a “guilty conscience”, for torpedoeing Queeg, Greenwald berates the others and himself in a prosecutorial tone for showing uncaring ignorance of those who had defended their country:

‘When I was studying law, and Mr. Keefer here was writing his stories, and you, Willie, were tearing up the playing fields of dear old Princeton, who was standing guard over this fat, dumb, happy country of ours, eh? Not us. Oh, no! We knew you couldn’t make any money in the service. So who did the dirty work for us? Queeg did! And a lot of other guys, tough, sharp guys who didn’t crack up like Queeg’.

When one of the acquitted officers proclaims that Capain Queeg had endangered the ship and the lives of the men, Greenwald retorts: ‘He didn’t endanger anybody’s life! You did! All of you! You’re a fine bunch of officers’.

Greenwald’s major scorn and recrimination, however, is reserved for the deceitful, manipulative and cowardly Keefer (“the man who should have stood trial”) – “the Caine’s favorite author, the Shakespeare whose testimony nearly sunk us all.” He confronts the understated Keefer as the evil influence and “real author” behind the entire mutiny:

You ought to read his testimony. He never even heard of Captain Queeg!…Queeg was sick. He couldn’t help himself. But you – you’re real healthy. Only you didn’t have one-tenth the guts that he had…I want to drink a toast to you, Mr. Keefer. From the beginning, you hated the Navy, and then you thought up this whole idea, and you managed to keep your shirts nice and starched and clean, even in the court martial. Steve Maryk will always be remembered as a mutineer. But you! You’ll publish your novel, you’ll make a million bucks, you’ll marry a big movie star, and, for the rest of your life, you’ll live with your conscience, if you have any. Now, here’s to the real author of the Caine mutiny. Here’s to you, Mr. Keefer.

One can only applaud when he subsequently empties the entire contents of his champagne glass over him.

Sublime movie making with insightful characterisations; it doesn’t get any better than this.

The Desperate Hours (1955)

Based on the novel and play by Joseph Hayes, and inspired by an actual event, ‘The Desperate Hours’, Bogie’s last hoorah, is a prototypical ‘besieged family drama’, a taut suspense filled thriller in which sleepy suburbia’s inviolate space is overrrun by a trio of criminals. Humphrey Bogart, Robert Middleton and Dewey Martin, are escaped convicts seeking an appropriate hideout until they can make contact with their money supply. Deliberately choosing the home of Fredric March and his family, and intent on avoiding trouble with the police, the cold-blooded Bogart knows he can cower the naturally protective parents into cooperating with him. The convict orders March, his wife Martha Scott, and their children Richard Eyer and Mary Murphy, to go about their normal activities so as not to arouse suspicion. Young Eyer, upset that March won’t lift a hand against Bogart, assumes that his father is a coward. The authorities are alerted when March, at Bogart’s behest, draws money for the convict’s getaway from the bank. Recognised by his adversary as a ‘thinking man’, March’s paternal instincts are pushed to the breaking point by Bogart’s taunts – “Clickety clickety Click Pop – those wheels keep turning”, yet slowly but surely he begins subtly turning the tables on the convicts.

Bogart’s character in ‘The Desperate Hours’ was originally written for a much younger man, thereby affording Paul Newman an early career highlight in the original Broadway production. The film was slated to co-star Bogart with his old pal Spencer Tracy, but this plan fell through when the two actors couldn’t agree on who would get top billing.

I have seen the 1990 remake of ‘The Desperate Hours’ with Mickey Rourke in the Bogart role and the always reliable Anthony Hopkins in the Frederic March role. The film, directed by Michael Cimino, was a commercial disappointment and received mixed reviews. Critic and movie historian Leonard Maltin referred to the film as: “Ludicrous…With no suspense, an at-times-laughable music score. Sadly, I must concur.

Recommended reading

Tough without a gun : The extraordinary life of Humphrey Bogart (Stefan Kanfer) 2011

Another one of my extravagant purchases, the £1.59 price sticker testimony to my parsimony. Such character traits are required in order to both support my interests, and to avoid alienating all the women in my family who are full of ideas about how best to spend my money!

I was initially drawn to page 253 and a list of the twenty highest grossing films in American history. There before me, was confirmation of Hollywood’s post-television obsession with demographics. If the economic power-shift to the young ensured a never ending supply of movies aimed squarely at getting them to purchase tickets, then the obvious corollary was an older generation intent on staying in to watch their television sets. As Kanfar explains – the move toward youthful male stars began in the early 1950’s when the US Supreme Court ordered the studios to divest themselves of the film theatres they owned and/or controlled. Just as they were losing the power of block booking – dictating what feature movie houses could show – television began to eat away at the potential audience. As my uncle once succinctly put it – the era when everyone went to the cinema was over.

I unintentionally anatagonise my family by regularly falling asleep in our local multiplex but really, what AM I to do? The warm thermostatically controlled environment, the comfortable seats and modern scripts that divest me of the need to think – it’s an arresting mix guaranteed to aid me immeasurably in my sonambulistic endeavours.

Beginning with ‘Avatar’ (2009) and ending nineteen entries later with the enchanting ‘Finding Nemo’ (2003), the list is populated with big budget extravaganzas such as ‘Lord of the Rings’, ‘Pirates of the Caribbean’ and ‘Shrek 2’. There would be little room for Bogie to flourish as an actor in today’s cinematic environment. Expressing regrets at the ‘current vulgarity of American dialogue and conduct’, Kanfer adds that in spite of his ‘rough-hewn persona and bar-room misbehaviour’ Bogart was ‘courteous to women and straightforward to men, and when he made a promise he kept it.’ If adults could only rediscover ‘emotional and aesthetic satisfaction’, then they might return in droves.

Comments

Humphrey Bogart was admitted to hospital in 1956 suffering from weight loss, a persistent cough, and difficulty swallowing. His symptons had begun about 6 months before admission with gradually progressive difficulty in swallowing foods. During the 6 months prior to hospitalization, he had lost approximately 30 pounds in weight and his frequent coughing spells, coming on in paroxysms, would often last for thirty minutes or more.

The man known to millions of cinemagoers as ‘Bogie’, had esophageal cancer and in early 1956 underwent a nine and a half hour resection of an esophageal tumor and adjacent lymph nodes. He also received postoperative chemotherapy. The actor recovered and regained some weight, but after six months he suffered a recurrence, for which he was treated with a course of radiotherapy. He remained at home during the next few months, where he died with the recurrent disease on January 14, 1957. For his family and friends, the loss was palpable yet in the eyes of the world, it was merely the beginning of a more than fifty year enduring odyssey that would make him one of the most iconographic stars of all time.

His widow Lauren Bacall published the first instalment of her two part autobiography in 1978 and the most extraordinary chapter recalls Bogart’s illness and death. The account is so detailed and raw that it seems as if Bacall is describing events that happened the day before, rather than decades earlier. At one point, she takes herself back to the night before his death; a night never to be forgotten of total restlessness, of Bogie picking at his chest in his sleep, of his feeling that he had to get up and then not, in effect, a sense of constant movement. She was awake most of the night and could see his hands moving over his chest as he slept, as though things were closing in and he wanted to get out. The only thing that became more apparent to her that night was an odor which she had been noticing as she kissed him. At first she thought it was medicinal but later realized it was decay. Initially she was unsure until the nurse told her what it was. The aroma was strong almost like disinfectant turned sour. She wrote that ‘In the world of sickness one becomes privy to the failure of the body—to so many small things taken for granted, ignored, I reacted not with revulsion but with a caving in of my stomach’. Revisiting her book years later, I am now sadly conversant with that aroma and of course, for my wife, who is an intensive care nurse, it has been part of her life for more than thirty five years.

I have often wondered what has made him such a ‘style icon’. What qualities did he possess to so effortlessly transcend generational tastes to remain the perennial calender and poster star? Without this visual omnipresence in retail outlets throughout the world, the only knowledge younger generations would have of Humphrey Bogart would typically come from the occasional cultural reference to ‘Casablanca’: “Here’s looking at you, kid”, which has eternally scorched its place in cinematic history.

He’d been acting for years but he didn’t join the ‘stellar immortals’ until his forty first year when he secured the starring role in ‘The Maltese Falcon’. He hadn’t even been first choice for the role, yet by the time international fame came knocking, he was ready to both embrace its benefits and to eschew its pitfalls.

‘Casablanca. established Bogart as the definitive romantic anti-hero complete with de rigueur signature style; the trench coat, fedora and a never-ending cigarette. The combination of the three helped Bogart attain the constantly wavering image of him as brooding, solitary figure and a ‘40s family man. Gone was the unbelted wool overcoat from earlier years.

His name is also interesting if only to suggest that there isn’t really anything in a name. “Humphrey” hardly screams style icon, but he didn’t ever let that affect his confidence. In fact, it was the perfect moniker for a man with a passion for the most staid yet intellectually stimulating sport ever – chess. On the flip side, his other admirable achievements include scoring the sexy Lauren Bacall on set. In time he would mix work with pleasure managing to tie the knot with her despite their nearly 25-year age difference. Yet the curiosity of Bogart’s life and his four marriages is that he wasn’t a womaniser. Friends and colleagues attest to a man who aspired to separate work from his private life. On set, he was always the height of professionalism, his courtship of Bacall rather tentative, behavioural traits commensurate with a man who was married to an alcolholic and physically abusive woman.

His celluloid image was brash and bold, wrapped in a neatly groomed yet equally complex package. Bogart’s look is as mysterious as it is mundane, at once seemingly out-of-reach yet somehow attainable. Even a passing glance at his signature style in Casablanca requires little explanation; a trench coat, a fedora and a never-ending cigarette. The combination of the three helped Bogart attain the constantly wavering image of him as brooding, solitary figure and a ‘40s family man. It was a slight evolution in image from his famed role in ‘The Maltese Falcon’ one year earlier when he wore an unbelted wool overcoat. But it was a move that forever brands Bogart as the boss of trench coats.

If you want the Bogart look, ditch the Marlboros – they’ll kill you eventually and with smoking now outlawed in public establishments, the cold air outside offers little hospitality. A keen eye for outerwear, the one area of attire that almost all men fall flat, will seal the image. Coincidentally, it’s also the only item that can make or break an entire ensemble.

I was thirteen when the realisation hit me that, for Humphrey Bogart, there was life after death. In the screen version of Woody Allen’s hit Broadway play, ‘Play it again, Sam’, the central character is a shy, retiring individual, a writer for ‘Film Quarterly’ who is consumed by movies, particularly his all time favorite, ‘Casablanca’. Unable to deal with the emotional turmoil of his impending divorce, Allan seeks solace in the movies he loves, imagining Humphrey Bogart (Jerry Lacy) as a regular visitor to his apartment in order to regale the beleagured central character with homespun philosophies on the fairer sex. “Dames are simple” he eulogises, appropriately garbed for a fleeting visit in fedora and trenchcoat; “I never met one that didn’t understand a slap in the mouth or a slug from a forty-five”. Allen cogitates but remains true to his sensitivity, before finding love with Linda (Diane Keaton). Like all of us, he’s realised he can only be true to himself:

Bogart: That was great. You’ve, uh, you’ve really developed yourself a little style.

Allan: Yeah, I do have a certain amount of style, don’t I?

Bogart: Well, I guess you won’t be needing me any more. There’s nothing I can tell you now that you don’t already know.

Allan: I guess that’s so. I guess the secret’s not being you, it’s being me. True, you’re – you’re not too tall and kind of ugly, but – what the hell, I’m short enough and ugly enough to succeed on my own.

Bogart: Hmmph. Here’s looking at you, kid.

My interest in Allen’s work rather waned in subsequent decades, but his early movies hold up well, and ‘Play it again, Sam’ was as close as anything to a career pinnacle.