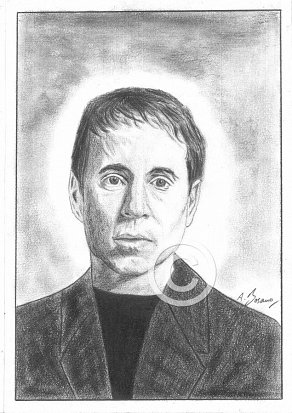

Paul Simon

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

The Best of Simon and Garfunkel (1999)

A useful starting point – A Columbia Records release containing 20 of the pair’s best tracks.

Bridge over Troubled Water (1970)

Undoubtedly, the most delicately textured au revoir to the 60’s from a major act; regrettable therefore that Simon’s memories of its conception remain so fraught. Interviewed two decades later by the English magazine Q, he was predictably succinct:

“I don’t have too many fond memories of that time. I remember the recording sessions. I don’t really feel too much. I don’t feel sad now but I have had that feeling in the past. It was a great period but….particularly during ‘Bridge over troubled water’, you know, we were not getting along. It’s really a pity – there’s this piece of work that is so much a part of so many people’s lives and so popular and so successful and yet for me the actual time that surrounded it wasn’t enjoyable”.

‘Bridge Over Troubled Water’, at its most ambitious and bold, particularly on its title track, was a quietly reassuring album; at other times, it was personal yet soothing; and at other times, just plain fun. The public in 1970, a very unsettled time politically, socially, and culturally, embraced it; and whatever mood they captured, the songs matched the standard of craftsmanship that had been established on the duo’s two prior albums.

Between the record’s overall quality and its four hits, the album held the number one position for two and a half months and spent years on the charts, racking up sales in excess of five million copies. The irony was that for all of the record’s worldwide appeal, the duo’s partnership ended in the course of creating and completing the album.

Paul Simon (1971)

There goes Rhymin’ Simon (1973)

Replacing worn out vinyl versions with shiny new compact discs was the 90’s ‘quality yardstick’ for album purchases. The handily sized, jewel boxed, sonic wonders offered little in the way of enhanced packaging, but the financial lure lay always in the music – that opportunity to rediscover a lost love dressed in new clothes and some previously overlooked delights.

Simon’s first two solo albums thematically mirror Lennon’s early post-Beatles releases. ‘Paul Simon’ and ‘John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band’ were cathartic releases for two songwriters freed of their 60’s shackles, but it would be their respective follow ups – ‘Rhymin’ Simon’ and ‘Imagine’ – liberally sacharrine coated for general consumption, that would set the charts alight.

Combining melodicism with R&B and gospel motifs, Simon crafts a near perfect concoction of songs at the famed Muscle Shoals studio, allowing the recording environment to further spark his muse. Kick-starting the proceedings with “Kodachrome,” and those wonderfully pungent lines – “When I think back on all the crap I learned in high school/It’s a wonder I can think at all” – Simon runs the full musical gamut from pop-rock production, 50’s doo-wop, soul and r & b. Vocally, if he’s missing Garfunkel, then there’s every attempt to hide the fact with his most assured series of vocal performances to date.

I always loved “Take Me to the Mardi Gras” for its Latin flavored evocation of wild abandon in New Orleans, its arresting Dixieland long form fade out a true musical surprise. I recall covering the song in my studio, Simon’s fluid acoustic fingerings an object lesson in textured vocal accompaniment.

I also tackled “Something So Right,” a ballad that begins in an offhand, almost conversational tone, before building into a declaration of great eloquence. Annie Lennox covered the song in the mid 90’s, but the original is, by far, more instrumentally varied.

The hand-clapping, call-and-response gospel anthem “Loves me like a Rock,” recorded with the Dixie Hummingbirds, has been a staple of Simon’s live act over the last forty years. Its infectious energy provides a fitting coda to a truly superb album.

If you don’t own ‘Rhymin’ Simon’, then you should.

Still crazy after all these years (1975)

Exploring the theme of a past relationship, Simon’s personality is well to the fore on the album’s title track, the lachrymose tone of the song’s middle eight engulfed in ruinous self-pity.

Four in the morning

Crapped out

Yawning

Longing my life away

I’ll never worry

Why should I?

It’s all gonna fade’

It’s the other side of his character, the world weary troubadour ever conscious of life’s transitory sensations – all that pain and misery and for what? As most self resilient people find – not very much. There’s black humour at work here, the seemingly more offensive his lyrical incisiveness becomes, the more I relish every line.

Simon’s third studio album, recorded in 1975, yielded four Top 40 hits, ‘Gone at Last’ , ‘My Little Town’, (his last studio collaboration with Garfunkel), ’50 Ways To Leave Your Lover’ and the title track. It won the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1976, Simon in jocular mood, acknowledging his indebtedness to Stevie Wonder’s lack of new product in 1975 – the Motown star had scooped awards throughout the preceding three years.

One Trick Pony (1980)

The first of Simon’s solo releases issued to less than universal acclaim, ‘One-Trick Pony’ was released concurrently with the film of the same name, proving conclusively, less than three years after his cameo appearance in Woody Allen’s ‘Annie Hall”, that the man had little future in movies.

Visually speaking, its a long drawn out experience, Simon sleepwalking his way through various domestic scenes complete with guitar case and cap in hand. Introspectively withdrawn, its a wonder his wife even notices his absence during arduous coast to coast tours, their marital tiffs by now, disturbingly benign. Partial redemption comes in the form of the accompanying soundtrack, an arresting mix of rock gospel and folk funk, superbly performed by some of the cream of LA sessioners such as Steve Gadd on drums and Tony Levin on bass.

The album is best known for the Grammy-nominated track “Late in the Evening” which was a hit for Simon in 1980, peaking at #6 in the U.S. Two of the tracks (the title song and ‘Ace in the Hole’) were recorded live at the Agora Theatre and Ballroom in Cleveland, Ohio in September 1979. The rest are studio cuts.

Interviewing the man on the set of his morose art house film, the BBC’s ‘Whistle Test’ presenter Annie Nightingale suggested few people would have been aware of his non collaborative songwriting contribution to the Simon & Garfunkel partnership. Reacting with a wry smile, he contested that this misconception was solely hers, virtually everyone being fully aware that Artie didn’t write – an embarrassing faux pas for one of Britain’s most respected disc jockeys.

‘Jonah’, ‘How the Heart Approaches What It Yearns’ and ‘Long, Long Day’ are bittersweet “adult” numbers that flirt with a Middle European modality as they further refine the shimmering, angst-under-glass folk-pop of ‘Still Crazy after All These Years’. Such tunes wistfully describe the rigors of a musician’s life on the road; the solitude, the physical exhaustion, the sense of futility and fear of obsolescence, the all pervading rationale for hanging up one’s guitar and getting a “real” job. Simon sings these ballads, which are weary to the point of effeteness, in a soft, whimpering croon, ably complemented but not overwhelmed by soft synth pad and electric pianos. ‘God Bless the Absentee’ breaks this instrumental wash, with a strident piano riff, searing guitar and deft rhythmic undertones from Gadd; its underlying theme succinctly encapsulating the tone of the movie.

My favourite Paul Simon album therefore, and a controversial view plainly at odds with most reviewers.

Hearts and bones (1983)

Graceland (1986)

Surprise (2006)

Recommended viewing

Paul Simon – Live At The Tower Theatre October 7, 1980

Clocking in at a mere 53 minutes, this release bears the hallmarks of a rather muted and understated affair, conspicuously lacking the hoopla and pazzaz associated with Simon’s artistic renaissance six years later. Seemingly in transition from the dark poetic sensitivity of his 60’s heyday and the artistic renaissance he would enjoy as an auteur for world music, Simon in 1980 was vying for pole position in the adult contemporary raceway.

The rough edges are gone but the troubadour still has a surprise or two up his sleeve; the solo electric guitar performance on ‘The Sound of Silence’, the heavyweight punch of ‘Late in the evening’ and his all new chiseled appearance, complete with hair transplant – Paul Simon at 39 suddenly looked ten years younger. The performance is sleek yet undercooked, but I’ll favour it on most days to the clattering sound of 101 African drums on his latterday concert DVDs.

Recommended reading

They’re out there, a small handful of scissors and paste biographies, each successive entry with little more to commend it beyond the basic updating of his timeline, yet Simon’s been married three times, was at the vanguard of 60’s social consciousness, and sparked political controversy with the recording of his ‘Graceland’ album. Surely, there’s a worthier biographical essay out there in the works from someone, somewhere? In the meantime try:

http://www.paul-simon.info/PHP/biography.php

An interactive biographical section that fans can regularly update, a newspaper archive and an extensive guitar tablature catalogue – truly a commendable exercise in “all things Simon”.

Comments

Describing his first impressions of the singer/songwriter for Playboy magazine in 1984, Tony Swartz wrote :

‘People meeting Paul Simon for the first time invariably remark about his height – 5’5”. I was more struck by how easily he commands whatever room he’s in. For a popular artist of his accomplishment, that partly comes with the territory. But he also gently exudes authority and clarity. He measures his words, edits as he speaks, and he sentences often sound written. Although he usually dresses unprepossessingly in jeans and T-shirts, his taste in nearly everything is highly cultivated, whether it’s in the art on his walls, the French pastel print fabric on his couches or the quality of the books on his shelves’.

It is precisely this attention to detail that ensures his irritation with the use of the word diminutive to describe his height. He’s small and happier to be described in that context.

Random House Webster’s College Dictionary defines the word ‘diminutive’ as : much smaller than the average or usual; tiny.

In America today, the average height for all males ages 20 and up, is 5’9.5”. If you ask a man who is 5’10” if he is short, he may reply yes because, for some unknown reason, we have this societal expectation that guys should be 6 feet tall, yet this is plainly untrue. A 6 foot tall man is well above average height. If Simon is more content being described as small, it’s because he understands that ‘diminutive’, whilst intended to be less condescending, is actually inaccurate.

His songwriting style is uniquely personal. By his own admission, he doesn’t envisage large themes engulfing his songwriting career, beyond perhaps the story of his life. There are the usual song subjects: love songs, family, social commentary, etc. And, of course the changing perspective of aging. His work readily divides into three distinct periods: Simon and Garfunkel, pre-‘Graceland’ solo albums and ‘Graceland’ to the present.

His voice is a more than adequate instrument to convey the sentiments of his incisive lyricism, although he clearly possesses a lesser set of pipes than Art Garfunkel. He has been musically articulate throughout his solo career in recognising the apparent lack of mid-range in his head voice, his judicious use of synth pads, electric pianos and gut string guitar all ensuring his vocals are spared competing for attention with other instruments within similar frequency ranges. Even when the brass section really breaks out on ‘You can call me Al’ (1986) he can be found taking a break from the mic. Of course, for those fortunate enough to catch he and Artie on their reunion tours, the sound of their voices coalescing is still akin to a pair of harmonising angels.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Simon

Simon’s approach to songwriting interests me as he underwent a dramatic change in the early 80’s from his general modus operandi. In much the same way as his friend Paul McCartney never referred back to his Beatles vocabulary after 1970, Simon eventually developed a system, something he had never utilised in his 60’s heyday. Interviewed by producer George Martin for his book ‘Making Music’ in 1983, he admitted that:

‘The way I wrote songs ten years ago was very different from my current method of working. After years of writing, I have only in the last two years developed a system. I used to work in bursts rather than slowly and steadily, but now I find that by putting in time every day – if I am in a writing period – I can get more done than if I just sit around and wait for a song to happen. One of the benefits of working like this is that one can see the entire germ of a song develop from start to finish. Working steadily, it generally takes me about four to six weeks to complete a song, but if I am not working steadily it can take from four to six months.’

Some of his most introspective work is to be found on the 1983 album “Hearts and bones”. Originally mooted as a Simon and Garfunkel reunion album, the pair famously fell out again on a world tour with Paul subsequently removing Artie’s vocals from the finished master tape. Personally, I didn’t discover the album until the late 80’s by which time, it had been consigned to obscurity by the enormous worldwide success of ‘Graceland’. .

Listening to the title track from that album, it’s easy to hear how Simon’s mature and honest ruminations on the “arc of a love affair” might have been overlooked in the flash-and-dash MTV era. Inspired by his relationship with Princess Leia herself, Carrie Fisher, “Hearts And Bones” is about how two people reconcile their expectations of an ideal love with the imperfections that life inevitably produces.

The musical accompaniment, little more than hand percussion and rhythmic acoustic guitar, is classic Simon, light and breezy enough to wrong foot any listener initially unprepared for the lyrical intensity of the subject matter. The idyllic tone poem imagery of the overture – “One and one-half wandering Jews” on a romantic getaway in New Mexico. contrasts with the unfolding discord of a “Love like lightning, shaking till it moans.”

Simon has spoken in interviews about how he was trying on the album to meld ornate and evocative language with conversational passages in a seamless manner. “What I was trying to learn to do was to be able to write vernacular speech and then intersperse it with enriched language, and then go back to vernacular,” he told SongTalk in 1991.

In this song, he uses the bridge to strip away all of the flowery observations about rainbows and mountains and reveals two people desperately trying to connect. She asks,_ “Why won’t you love for who I am/Where I am?” He replies, “’Cause that’s not the way the world is baby/This is how I love you, baby.”_

The illusion shattered, the pair “return to their natural coasts” to “speculate on who has been damaged the most.” Sadly, the “arc of a love affair” is now “waiting to be restored.” Yet Simon’s closing lines illustrate how two people in love remain intertwined even after their separation: “You take two bodies and you twirl them into one/Their hearts and their bones/And they won’t come undone.”

The irony behind the song is that it was written before Simon and Fisher were married and divorced, almost in helpless anticipation of their future travails. In essence, “Hearts And Bones” prefaces the unpalatable aspects of love whilst acknowledging its inevitability.

Simon & Garfunkel were already successful by the time they released their fifth album together early in 1970, but “Bridge Over Troubled Water” sent them ballistic. At the dawn of a new decade, with civil unrest in America and protest mounting against the escalation of the war in Vietnam, the title track was welcomed as a soothing balm for troubled times.

Paul Simon has said that his inspiration for the song came from “Oh Mary Don’t You Weep”, a recording by a gospel group called the Swan Silvertones, on which the singer scats: ‘I’ll be your bridge over deep water…’

Originally conceived on the guitar, Simon would delegate primary instrumental duties to Wrecking Crew member Larry Knechtel, who would win a Grammy for his pianistic efforts. Set in a gospel frame with rising 4th/5th/9th major chords, Garfunkel’s translucent vocal and a climactic final verse, all these elements combined to make “Bridge Over Troubled Water” a song not just of its time, but for all time.

More tellingly, despite recognising the composition as conceivably his greatest, Simon was astute enough to subordinate his ego to the greater demands of the song, by allowing Garfunkel to take the vocal helm. It is nigh impossible to imagine any other songwriter of the modern era being this magnanimous. More importantly, he was correct in his thinking; all his subsequent reinventions of the song within a ‘live’ context never less than interesting, yet conspicuously devoid of the original’s majestic pomp and sweep. Phil Spector would have been proud.

The opening words (“When you’re weary”), sung plaintively by Garfunkel, spoke of disturbances past (Watts, MLK) and promised succour for dramas yet to come. It was an oddly old-fashioned message for the hippy times, delivered in quaint, almost courtly language (“I will lay me down”). The music was less countercultural than conventional, a Bacharach ballad for longhairs, and although the lyrics (“Your time has come to shine”) were cliched schmaltz, against the epic backdrop of strings and echoing drums they seemed like secret messages. This was an easy listening panacea for the Woodstock children and testament to the magnificent healing power of pop.

When the split finally came, Simon was afforded the opportunity of a solo career recording harder-edged music, and over the next 30 years he developed into a fascinating and eclectic craftsman. Yet, even today, 43 years since the world first heard the song, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” remains a benchmark.