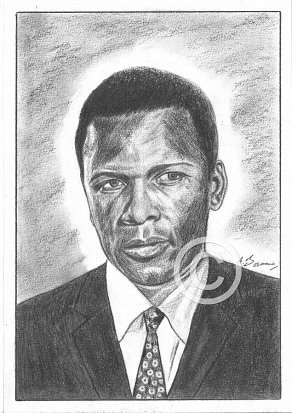

Sidney Poitier

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

To Sir with love (Original motion picture soundtrack)

1. To Sir With Love (Lulu) 2:49

2. School Break Dancing “Stealing My Love from Me” (Lulu) 2:02

3. Thackeray Meets Faculty, Then Alone (Instrumental) 4:04

4. Music from Lunch Break “Off and Running”(The Mindbenders) 2:01

5. Thackeray Loses Temper, Gets an Idea (Instrumental) 2:13

6. Museum Outings Montage “To Sir, With Love” (Lulu) 3:29

7. A Classical Lesson (Instrumental) 5:18

8. Perhaps I Could Tidy Your Desk (Instrumental) 0:54

9. Potter’s Loss of Temper in Gym (Instrumental) 0:52

10. Thackeary Reads Letter About Job (Instrumental) 0:57

11. Thackeray and Denham Box in Gym (Instrumental) 1:35

12. The Funeral (Instrumental) 3:24

13. End of Term Dance “It’s Getting Harder All the Time” (The Mindbenders) 2:15

14. To Sir With Love (Lulu) 1:12

The soundtrack to 1967’s ‘To Sir With Love’ features the famous title track by Scottish diva Lulu, as well as two alternate versions of the song with revised lyrics and arrangements. Lulu also sings ‘Stealing My Love From Me’, whilst the Mindbenders ramp up the tempo with two numbers, “Off and Running” and “It’s Getting Harder All the Time.” An enjoyable nugget of ’60s pop culture although desparately short on playing time; clocking in at around thirty minutes, the non inclusion of supplementary material to flesh out the collection remains a mystifying decision.

Recommended viewing

The Blackboard Jungle (1955)

Released in 1955 and based on Evan Hunter’s ferocious attack on inner city schooling, the film iconised Poitier in the popular consciousness and, nearly sixty years later, stands as a seminal piece of theatrical cinema. Poitier, as Gregory W Miller, a juvenile delinquent eventually rehabilitated by Glen Ford, broke all the wider stereotypes of the teenage black threat. The film -decried by Congresswoman Clare Booth Luce as ‘un-American’ – was released in the same year as the Brown vs Board of Education Supreme Court ruling that unanimously voted in integrated education.

Edge of the city (1957)

The Defiant ones (1958)

Lillies of the field (1963)

In his Best Actor Oscar winning role, the first black man to do so, Poitier plays Homer Smith, an aimless ex-GI who takes a temporary handyman job at a Southwestern farm maintained by five German nuns. It is the cherished dream of the Mother Superior (Lilia Skala) to build a chapel and the realisation of her goal arrives in the form of young Homer. Despite his protestations, he sets to work endearing himself to the surrounding townsfolk, whilst avoiding arrest for a previous crime.

Shot in two weeks under auspicious circumstances; director Ralph Nelson had collatorised his home to raise finance and Poitier had waived his usual salary in lieu of any profits, the movie handsomely rewarded all those with faith in the project.

Viewing the film with the benefit of hindsight, as I did recently, it’s nigh impossible to avoid the notion of powerful Civil Rights overtures to the Awards Committee for positive discrimination in making Poitier the first black man to win the Oscar for Best Actor. Pitted, as he was that year, against strong competition from Albert Finney, Richard Harris and Paul Newman, his essentially lightweight performance as the handyman building a new chapel for a group of German nuns hardly seems front runner material. Whilst there’s a hint of tension with the construction company foreman when Homer applies for a paid position, racial issues are consigned to the background, and for the most part Poitier remains all hard-working decency and will-to-succeed personified. Skala’s steely Mother Superior thankfully seasons the feelgoodery, but the other sisters contribute twee comedic misunderstandings and back-up chorus to Poitier’s symbolic hot gospelling. There’s even a hint of jive talking in one of their early english lessons which Homer delivers with good natured aplomb. All in all, a feelgood movie for the times but Poitier got better when he got angrier for ‘In the Heat of the Night’ four years later.

As an aside, the role of the priest was played by Dan Frazer, a television veteran making his big screen debut at the age of forty two. Like millions, I remember him as Kojak’s boss in the long running 70’s hit series about a New York cop, all peptic ulcers and protestations at Theo’s maverick policing tactics.

A Patch of blue (1965)

To Sir with love (1967)

Poitier stars as Mark Thackery, a Black engineer, born in British Guyana and educated in California, who takes a job teaching at a high school in a depressed area of London. The position is an interim one whilst he seeks an engineering post. His class is comprised of unruly ruffians and in order to overcome their rebelliousness, he junks conventional academics in favour of their ‘preparation for life’ in the outside world. Whether delivering culinary lessons, hints on female deportment and make up, or outings to local museums, he works at instilling a mutual love and respect amongst themselves.

Judy Geeson is Pamela Dare, the blond beauty at odds with her divorced mother’s moral lifestyle, who develops a crush on Thackery. Christian Roberts is Devin, the leader of the group, consistently opposing Thackerey’s unorthodox methods until their inevitable pugilistic confrontation in the school gymnasium.

The fashions and language inevitably have a dated feel but the universal themes of adolescent awakenings and rebelliousness remain topical.

In the heat of the night (1967)

As Philadelphian Detective Virgil Tibbs, pulled into a murder investigation run by Chief Bill Gillespie (Rod Steiger) in a small town in the Deep South, the film provided Poitier with his most considered screen persona. The production was for years an academic protectorate with both Poitier and Steiger regularly appearing as guest speakers at American symposiums dedicated to the film.

In the movie, African-American northerner Virgil Tibbs is picked up at the train station whilst awaiting his connection with a substantial amount of cash in his wallet. Gillespie, prejudiced against blacks, jumps to the conclusion that he has his culprit but is eventually embarrassed to learn that Tibbs is an experienced Philadelphia homicide detective who is simply passing through town after visiting his mother.

Observing the amount of cash in Virgil’s wallet, Gillespie exclaims:

‘Coloured can’t earn that. It’s more than I make in a month! Where did you earn it?!’ Tibbs outlines the various US states in which he has worked but his interrogator remains unconvinced.

‘Just how do you earn that kinda money?’

‘I’m a police officer’ replies Tibbs, an undercurrent of frustration now evident in his voice as he throws his badge on the desk.

Gillespie admonishes Sam Wood, his arresting officer before Tibbs, in an attempt to corroborate his story, inadvertently pours lighter fuel on the fires of racial prejudice by offering to pay for the phone call to his boss

‘How much they pay you to do their police work?’

‘A hundred and sixty-two dollars, and thirty-nine cents per week’ replies Virgil, the very precision of his answer barely concealing his contempt for the backwater mentality now engulfing him.

Gillespie, suitably dumbstruck, exclaims for all to hear:

‘A hundred and sixty-two dollars and thirty-nine cents a week? Well boy! Sam, you take him outside but treat him nice, because a man that makes a hundred and sixty-two dollars and thirty-nine cents a week, we do not want to ruffle him!

Steiger won the Best Actor Oscar for his portrayal of the bigoted Chief Gillespie who develops a grudging admiration and respect for his shanghaied assistant. Strong characterisation, effective pacing, a stirring score from Quincy Jones and a rousing title song from Ray Charles, all contribute to this classic movie.

Nowadays, on the odd occasion we encounter something worth seeing, I sit with my wife in our local cinema as the forthcoming attractions are previewed and the look we give each other says it all as one CGI epic after another is rolled out. It’s so easy to dismiss ‘our problem’ as a generational one, yet as youngsters, our regular visits to the cinema encompassed the full range of film making, from high adventure yarns to thought provoking films with social issues. My father was paying for the ticket, the least he could expect of me was a little thought here and there.

Guess who’s coming to dinner (1967)

(See main commentary)

Shoot to Kill (1988)

Poitier’s first film in a decade and an action thriller that raises the bar for its genre, thanks to a strong script, beautiful cinematography and astute casting. There’s enough red herrings amongst Kirstie Alley’s trail guide rogues gallery to keep any seasoned cinemagoer guessing, and the impending storm hardly helps our FBI man to hunt down his killer.

Principal photography around Washington State featuring breathtaking scenery near Pugent Sound, taut direction from Roger Spottiswoode and a combustible relationship between Poitier, (still a believable action hero at sixty one) and Tom Berenger, all pleasingly combine to produce what was a critically well received movie.

Mandella and De Clerk (1997) (Tv movie)

The secret life of Noah Dearborn (1999)

Like vintage wine, Poitier would effortlessly mature, defining each decade of his career with a minor celluloid classic. His character Noah Dearborn is a Frank Capra hero for the millenium, described by the clinical psychologist (Mary-Louise Parker) as ‘a miracle uncorrupted by modern life.’ It’s a judgment her developer boyfriend George Newbern strenuously rejects, still bristling from Dearborn’s resistance to an escalating six-figure deal to buy his land. Under pressure from ‘the top’ to commence construction work on a shopping mall, he wants the veteran master joiner declared mentally incompetent.

Dearborn’s ability to resist the ravages of time – he’s 91 but looks like a man in his 60’s – is the evolutionary result of a dedicated life. Flashbacks offer insights into his character. His uncle advised, “When a man loves his work, truly loves it, sickness and death will get tired of chasing you. And just finally give up and leave you alone.”

Under construction.

Recommended reading

Sidney Poitier – The Measure of a Man: A Spiritual Autobiography (2007)

“I don’t mean to be like some old guy from the olden days who says, “I walked thirty miles to school every morning, so you kids should too.” That’s a statement born of envy and resentment. What I’m saying is something quite different. What I’m saying is that by having very little, I had it good. Children need a sense of pulling their own weight, of contributing to the family in some way, and some sense of the family’s interdependence. They take pride in knowing that they’re contributing. They learn responsibility and discipline through meaningful work. The values developed within a family that operates on those principles then extend to the society at large. By not being quite so indulged and “protected” from reality by overflowing abundance, children see the bonds that connect them to others.”

Comments

Last Update : 20/3/13

The white chief of police and the black homicide investigator begin questioning the wealthy plantation owner about the recent death of a wealthy business entrepreneur from Chicago who was planning to build a factory in Sparta, Mississippi. Mr Endicott, who represents the very worst in a perceived white Anglo Saxon Protestant supremacy that has bedevilled the southern US states for decades, is initially cordial towards the coloured officer and noting his obvious interest in horticulture, asks Virgil Tibbs, the man he has just been introduced to, whether he has a favourite flower. Tibbs confesses a partiality towards epiphytics whereupon Endicott eulogises on the correlation between this type of orchid and the negro race since both require care, feeding and cultivating. As the conversation progresses, Endicott realises that he is a suspect and slaps Tibbs whereupon the officer slaps him back. “There was a time” the clearly agitated host confirms, “when I could have had you shot.”

The scene is from “In the heat of the night,” a full three years after passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, and one of the first times in any major motion picture where a black man has reacted to provocation from a white man in such a way. There is some uncertainty about the origins of the scene; whether it existed in first draft form or whether it was included at the insistence of the forty year old actor portraying the homicide expert. Either way, it was symbolic of Sidney Poitier’s lifelong involvement in black activism, a role he would be ultimately recognised for on August 12, 2009, when he was awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian honour, by President Barack Obama. Surpassing even the heights he had scaled as an Oscar winning actor, the award symbolised his lifelong campaign for racial harmony, in essence his cri de coeur.

\http://www.zimbio.com/pictures/8Kk0oD_kAFQ/Obama+Honors+Sixteen+Congressional+Medal+Freedom/3gNM9MC8aQx/Sidney+Poitier\

In his 2004 book ‘Sidney Poitier – Man, Actor, Icon,’ Aram Goudsouzian wrote that:

If Sidney Poitier had an acting trademark, it was the cool boil. In the movies, when injustice drove him to the brink, he became a pot of outrage on the verge of bubbling over. His eyes would blaze. His mahogany skin would tighten. His words would gush out in spasms of angry eloquence, carefully measured by grim, simmering pauses.

But the powder keg never exploded. It could not explode. For over a decade, from the late 1950s to the late 1960s, Poitier was Hollywood’s lone icon of racial enlightenment; no other black actor consistently won leading roles in major motion pictures. His on-screen actions thus bore a unique political symbolism. The cool boil struck a delicate balance, revealing racial frustration, but tacitly assuring a predominantly white audience that blacks would eschew violence and preserve social order.

On 22 August 1967, life imitated art. During a televised press conference in Atlanta, reporters peppered Poitier with questions about urban riots and black radicals. Race riots had ravaged Newark and Detroit during a summer that had also seen race-related civil disorders in a spate of other cities. For five minutes, Poitier answered the questions. Then came the reined-in rage. “It seems to me that at this moment, this day, you could ask me about many positive things that are happening in this country,” he lectured. Instead, the reporters fixated on a narrow segment of the black population. The movie star admonished their tendency “to pay court to sensationalism, to pay court to negativism.”

Poitier further objected that the media had crowned him a spokesman for all black America. With controlled fury, he refused to be defined only by his skin color. “There are many aspects of my personality that you can explore very constructively,” he seethed. “But you sit here and ask me such one-dimensional questions about a very tiny area of our lives. You ask me questions that fall continually within the Negroness of my life.” He demanded recognition of his humanity: “I am artist, man, American, contemporary. I am an awful lot of things, so I wish you would pay me the respect due.” His soliloquy won applause from the abashed reporters, who then confined their questions to the actor’s career.

The first time I ever saw him on the big screen was in “To Sir with Love”, a film he had come to Britain to film during the mid 60’s. He was in his late thirties and an established star, having previously won the Best Actor academy award in 1963 for “Lillies in the field”. Of course, he didn’t look anything like his age, thereby further enhancing a portrayal, even beyond the scope of his natural acting talent, of an engineering graduate who takes a temporary teaching post in London’s East End.

The apex of Poitier’s cinematic social conscience was reached during the filming of “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner,” Hollywood’s flawed idea of a stirring call for racial justice. The initial premise, a young white woman falling madly in love with a black man while visiting the University of Hawaii and bringing him home to San Francisco to get her parents’ eventual blessing was widely ridiculed as dated by liberal critics.

Spencer Tracy, in his last ever role, is the father, a crusading newspaper publisher whilst his real life long term partner, Katharine Hepburn, plays his wife, a modern art dealer.

A box office smash at the time, and a recipient of ten Oscar nominations, Poitier, is the impossibly handsome doctor with Johns Hopkins and Yale on his résumé and a Nobel-worthy career fighting tropical diseases in Africa for the World Health Organization. He’s the acceptable face of ‘black’ for white America, a man but a few heartfelt conversations away from every couple’s ideal son-in-law. Encapsulating this idealism is his unworldly bride to be – “He’s so calm and sure of everything, – doesn’t have any tensions in him.” She is confident that every single one of their bi-racial children will grow up to be President of the United States and have colorful administrations.”

As Mark Harris reminded me recently when I read his book, “Pictures at a Revolution,” it was not until the year of the movie’s release that the Warren Court handed down the Loving decision overturning laws that forbade interracial marriage in 16 states.

http://www.slate.com/articles/arts/books/2008/03/hollywood_archaeology.html\

Loving v. Virginia, 388 U.S. 1 (1967), was a landmark civil rights decision of the United States Supreme Court which invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage. The case was brought to trial by Mildred Loving, a black woman, in an attempt to overturn her white husband’s one year prison sentence, a direct result of their Virginian marriage. The union violated the state’s anti-miscegenation statute, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which prohibited marriage between people classified as “white” and people classified as “colored.” The Supreme Court’s unanimous decision held this prohibition was unconstitutional, overturning Pace v. Alabama (1883), freeing Richard Loving and ending all race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States.

The Supreme Court decision was reached after filming wrapped thus explaining the inclusion in the final cut of the outdated line referring to the possibility of the young couple’s nuptials being rendered illegal. The reverberations of this constitutional crisis reached all the way to the White House that same year when L.B.J.’s secretary of state, Dean Rusk, offered his resignation after his daughter, a Stanford student, announced her engagement to a black Georgetown graduate working at NASA. The offer was repudiated.

It was immensely difficult for Poitier to please any faction throughout the 60’s. Racial taboos precluded him from romantic roles. His pattern of sacrifice for his white co-star rankled many blacks and his characters often seemed stripped of any black identity, instead promoting an exaggerated colorblindness. By 1967, the year of his greatest cinematic success, many radicals, college students, and film critics were condemning his recurring role as a noble hero in a white world. This view, in my opinion, was unfair for until the mid-1960s, few Poitier films played in the Deep South. He was confronting difficult choices, the need to balance mass appeal and political viability, an equilibrium difficult to maintain for any celebrity in a similar position. In due course, his efforts would be widely recognised.

More than forty years later as Barak Obama’s presidential bid reached its zenith in Atlanta a week before polling day, Poitier, also in the same state, delivered the keynote address at the tenth annual convention of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the civil rights organization led by Reverend Martin Luther King Jr. The struggle for black equality had by then reached a crossroads. A decade of nonviolent demonstrations had won basic constitutional rights for black southerners, but had achieved little for the northern ghettos that burst into violence that summer. Moreover, a new generation of leaders now challenged King’s core message of nonviolence and integration, in much the same way as his late father’s message had been challenged before his untimely assassination. That month H. Rap Brown, president of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), had told 300 young blacks in Maryland to fight white racism with eye-for-an-eye violence. “Don’t love him to death,” he implored. “Shoot him to death.” His rhetoric ignited a riot. In this volatile atmosphere, SCLC needed to maintain relevance. The Atlanta summit’s theme was “Where Do We Go from Here?”

Before 2,000 delegates at the opening banquet, King introduced his “soul brother.” Then Poitier orated, by celebrating the huge majority of peaceful blacks, condemning the “turmoil and chaos” that ruled politics, praising King as “a new man in an old world.” When Poitier declared his continued devotion to civil rights, many delegates wept. Like King, who promoted economic boycotts as alternatives to riots, Poitier maintained faith in peaceful protest and interracial brotherhood.

The civil rights movement had shaped the contours of Poitier’s career. Nonviolent demonstrations for black equality have forged a culture in which his image resonates, and his movies have engendered racial goodwill. Being such a strikingly different type of actor, he has shouldered political burdens generally unreserved for members of his acting profession.

Sidney Poitier has been an actor prodigious in talent yet has singularly failed to devote all his energies to his craft in search of worthier causes. Stanley Kramer once called him “the only actor I’ve ever worked with who has the range of Marlon Brando—from pathos to great power.” Poitier infused grace and dignity into his characters, and he exuded a warm charisma. Moreover, he possessed that indefinable quality of a true movie star, namely an aura, a presence that dominated the screen; small wonder therefore, that Hollywood chose him as its single black star, due in large part, to his exceptional magnetism.

Today, he remains a restless questioning soul. In his book “Life beyond measure – letters to my great-granddaughter” he recounts the moment he met his fourth generation offspring in 2005:

“It began with an awareness that I was more cognisant than anyone else of the four generations of women present there that day, which allowed me, as I stood looking at Ayele in her mama’s arms, to focus even more closely on the child – on the stark differences between us and on our unique kinship. She and I were connected by virtue of the contrast, in that I was not far from eighty and she was two days old. Beyond the realisation that she had just arrived and that I was moving toward the end of a journey, my thoughts unfolded next to consider all the history that had transpired between my own arrival and hers.”

In his first letter to his great-granddaughter he writes :

“Though these letters are addressed to you, dearest Ayele, they are also written for me, so that I can rest assured in knowing that you will have me as a steadfast presence in your life – evn after i’m gone and you are older. Much as I would have it otherwise, chances are that I will not be around long enough for you to know me well. Even so, on these pages, you will find me waiting whenever you choose to visit.”

Happily, I can report, as of this writing, that Ayele has recently celebrated her seventh birthday and is still actively involved with her great-grandfather which must be wonderful for her. I too had the good fortune to spend time with my great-grandfather until I was nine and the memories linger to this day.

Poitier’s spirituality is more evident in this volume than in his previously published memoirs yet I must confess surprise at his ambivalence towards subscription to a particular denominated faith. His views are informed by Christianity, but also by other influences, including the Caribbean voodoo practiced by his Bahamian mother and thinkers such as Carl Sagan.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carl_Sagan\

Without saying it explicitly, Poitier worries that the world his great-granddaughter inherits will be continually threatened by religious conflicts. God, he pleads, “is for all of us. It is not a God for one culture, or one religion, or one planet.” Amen to that.