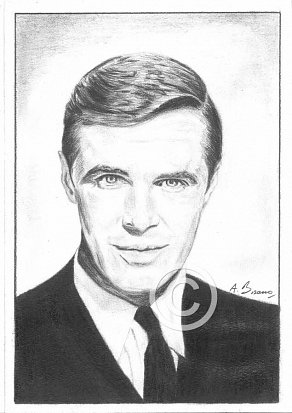

George Peppard

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Breakfast at Tiffanys (1961)

Well its Audrey Hepburn’s film really but constant re-screenings at least remind viewers that Peppard acquitted himself ‘handsomely’ in more ways than one.

The Carpetbaggers (1964)

There are parallels to be observed between Peppard’s character and that of Howard Hughes in what is arguably one of his two finest screen appearances. This film was notable also for the last filmed appearance of Alan Ladd before his premature death.

Operation Crossbow (1965)

An earlier appearance with Jeremy Kemp (Willi in the “Blue Max”) and a thoroughly enjoyable mainstream WWII romp as special agents attempt to destroy German V2 rocket sites.

The Blue Max (1966)

See above.

Banacek Tv series (1972-74)

Arduous shooting schedules brought about the early demise of this series after just two seasons. David Janssen aged fifteen years in looks over the course of four seasons of the long running hit series “The Fugitive” and Peppard probably foresaw a similar fate for himself. It’s an unrelenting schedule leaving precious little “family downtime” and the actor predictably lost interest.

Recommended reading

Tellingly, I am unaware of any major biography of this actor. He nearly landed the main role in the 80’s long running US tv series “Dynasty” which may well have brought him more “mainstream attention”. As it is, barring a few potted internet resources, there appears nothing. In fairness though, what is there to write about most of us? He was an actor, he did his job, finito.

Surfing

https://www.rogerebert.com/reviews/pj-1968

A 1968 interview conducted by journalist Roger Ebert.

\http://users.telenet.be/LadyByron/html/george_interviews.html\

A mid-80’s profile of the man, financially crippled by alimony payments to multiple ex-wives, hence some of his latter day career choices in films and television. Peppard appeared by this stage, to be reconciled to his drinking and difficult personality.

Comments

Last updated : 27/5/21

George Peppard Byrne, Jr. October 1, 1928 – May 8, 1994) was an American film and television actor.

He secured a major role when he starred alongside Audrey Hepburn in Breakfast at Tiffany’s (1961), portrayed a character based on Howard Hughes in The Carpetbaggers (1964), and played the title role of the millionaire sleuth Thomas Banacek in the early-1970s television series Banacek. I remember the series well containing as it did, some innovative story lines for its day.

He is sadly and probably best known for his role as Col. John “Hannibal” Smith, the cigar-chomping leader of a renegade commando squad, in the 1980s television show The A-Team. My prime time television viewing days were long gone by the early 80’s but I recall younger relations avidly following the series. In fairness they probably weren’t watching it for Peppard but rather Mr T (Laurence Turead) and he probably knew it himself. In summary therefore, the early promise of his career was not fulfilled and yet I recall him with some regularity in the rather disconcerting way one of his most popular films mirrors true life people I have known.

I was too young to see “The Blue Max” when it appeared in the cinema in 1966 but I recall becoming acquainted with the movie in the early 70’s. Much later it had a rescreening in 2008, and I had the opportunity of catching up with it again.In revisiting the central characters during this welcome transmission I was reminded of the “very worst” of acts that people are capable of committing. The beneficial effect on me was not immediate but the underlying themes in the film enabled the ‘merest anchoring’ of my true self to take seed once more.

In the movie, German Corporal Bruno Stachel (George Peppard) leaves the fighting in the trenches to become an officer and fighter pilot in the German Army Air Service. Joining a squadron in spring 1918, he sets his sights on winning Imperial Germany’s highest military decoration for valor, the Pour le Mérite, nicknamed the “Blue Max”, for which he must shoot down twenty aircraft.

Coming from humble origins, Lieutenant Stachel is driven to prove himself better than the aristocratic pilots in his new fighter squadron, especially Willi von Klugemann (Jeremy Kemp). Their commanding officer, Hauptmann Otto Heidemann (Karl Michael Vogler) is an upper-class officer whose notions of chivalry conflict with Stachel’s ruthless determination.

The film moves to an inevitable denouement in the command room, in effect a ramshackle hut built on an airstrip where Count for Klugermann (James Mason) is informed by a telephone call from the Field Marshall that Stachel is to be court marshalled for falsely claiming two “kills” shot down by the late Willi Von Kugermann (his nephew). Being an older man and “understanding of these sorts of things”, the Count has overlooked his much younger wife’s indiscretions with her nephew by marriage. We must presume at this stage that he only suspects his wife of having slept with Bruno as well. Nevertheless her penchant for fighter aces ensures that this brief interlude with Stachel has wider implications. Once she has confessed to informing the Field Marshall of Stachel’s bedroom confession and that she finds him “an upstart – he insulted me” her husband taunts her. “So you really lost your head this time – the Field Marshall is insisting on a court of enquiry – they are going to disgrace him – an officer with the highest decoration Germany can give – all because of your stupid little anger do you understand? Do you? (Stachel had refused to elope to Switzerland with her after the award ceremony) The Count continues “When they do that they disgrace the whole German officer corps”.

At that precise moment, Otto Heidemann, who has barely escaped with his life test piloting the new mono fighter plane, bursts into the hut informing the Count that the struts are too weak for the wing loading stress and that he was lucky to get down alive. The Count is overcome by the very worst practicality of the situation and Stachel is ordered up in the air to give the watching crowd “some real flying”. Kaeti (played by Usula Andress) half heartedly motions towards the door to warm Stachel but James Mason’s imperious tones stop her in her tracks. “Sit down, sit down” and she does seemingly anaesthetised to the impending consequences of her actions. Stachel’s fate is sealed as his plane breaks up in mid air and the Count rubberstamps his war record file just before the debris hits the ground. Ignominy avoided and military chivalry upheld the Count sees to it that the file of a German officer and war hero is sent to the Field Marshall. He then cajoles his wife “Stand up Kaeti, we’ll be late for lunch” as Ursula subsequently makes for the door, her tears drying with each footstep.

Waiting on the ground for his instructions, Stachel would have been in safer hands amidst the carnage of trench warfare. Hell truly hath no fury like a woman scorned – for the Kaeti character we can perhaps extend some degree of pity for her lack of ‘military awareness’ but for those women we have all known who lack comparable naivety then no such sentiment can be offered. Let us now revisit the circumstances that led to Stachel’s death.

Kaeti’s unbridled vanity compels her to believe that Willi has lost his life ‘duelling over her’ in the air with Bruno. As the two pilots are returning to their base, Willi challenges Stachel and spotting a bridge, dives under the wide middle span. Stachel tops him by flying under a much narrower side one. Seething, Willi does the same, but clips the top of a nearby brick tower afterward and crashes. At no subsequent point in the film can Kaeti believe that they were only competing against each other as pilots until of course Bruno takes relish in telling her so. She would have known had the opportunity arisen to eavesdrop on the two protagonists in an earlier scene. When Willie is made aware that his ‘Aunt’’ has also bedded Bruno he is moved only to shout at Stachel – “We’ve (the squadron) tolerated you for long enough.” There was no way these two men were going to come to blows over Kaeti (whatever any woman’s natural inclination to “come first”) because both of them knew precisely the sort of female she really was – shallow, vain, manipulative and very bored with her life in general but nonetheless “prepared to endure it” for the social standing and lifestyle her marriage afforded her. One only has to contrast the Countess to Otto’s wife in the movie (her commitment to nursing the injured soldiers and her concern for her husband right through to the last reel), to understand why.

When Stachel reports his death, Otto Heidemann presumes that the two verified victories were Willi’s. Insulted, Stachel impulsively claims the kills, even though it is discovered that he only fired forty bullets before his guns jammed. Outraged, Heidemann reports Stachel’s suspected lie to his superiors, but is told that Stachel’s victories (obliquely in the interest of media expediency) will be confirmed. Later, alone with Kaeti, Stachel makes his fatal mistake and admits he lied. Post coital euphoria can lead men to admit the most extraordinary things for as he says at the time “Willi was a fool but I was the bigger fool – I can get twenty kills myself.”

In any final analysis of the two sexes and the questions posed by this film, it is perhaps fair to say that very few women would have knowingly sent Stachel to his death (the Countess merely wanted him stripped of his Blux Max medal) and the Count, like many men, whilst equally unlikely to have made the initial malicious phone call had roles been reversed, was more than capable of resolving the situation in his mind. It’s a chilling finale to one of the best war films of all time, suitably adorned with stunning aerial photography and a majestic sweeping score from Jerry Goldsmith. If for no other reason than this film, I will always remember George Peppard.

A cursory glance at Wikipedia indicates that he was married five times and fathered three children. One would presume most people would determine that marriage is not perhaps numbered amongst their finer strengths after two failed attempts but bless them all in Hollywood, they keep trying. His lifestyle with drink and tobacco was also deeply injurious to his health and undoubtedly contributed heavily to his early demise. He had undergone surgery for lung cancer in 1992, two years before his death. In remission after a tumor was removed from his right lung, he entered the UCLA Medical Centre in 1994 with breathing problems that developed into pneumonia. A longtime heavy drinker and smoker, Peppard abandoned alcohol in 1978 and kicked his two-pack-a-day cigarette habit after the lung surgery in 1992.

Known as difficult in his professional and personal life, the versatile actor suffered long periods of unemployment and four divorces, two from actress Elizabeth Ashley, whom he met while filming “The Carpetbaggers.” “Getting married and having a bad divorce is just like breaking your leg. The same leg, in the same place,” joked the tall, ruggedly handsome Peppard a few years before his passing. “I’m lucky I don’t walk with a cane.”

Peppard proved as pragmatic as he was outspoken. Although he originally disparaged the small screen in favor of films, he achieved his widest success and perhaps greatest pleasure starring in three NBC television series—as the Polish American detective “Banacek” from 1972 to 1974, as a neurosurgeon on “Doctors’ Hospital” from 1975 to 1976, and as the Vietnam veteran colonel on “The A-Team” from 1983 to 1987.

Peppard appeared in more than 25 films after making his debut in “The Strange One” in 1957. But his first were the best “Pork Chop Hill” in 1959, “Home From the Hill” in 1960, his role as the writer supporting Hepburn’s Holly Golightly in “Tiffany’s” in 1961, “How the West Was Won” in 1962 and “The Carpetbaggers” in 1964. Although he appeared with the superstars like Gregory Peck, Robert Mitchum, James Stewart, and John Wayne, he never became one himself.

There were lean years but then, with the tough-guy stereotype he always attributed to his role as a megalomaniacal tycoon in “Carpetbaggers,” Peppard was tapped for leader of “The A-Team,” which he came to rate as the best role of his career.

“I thought the pilot was terrific,” he told The Times shortly after the series debuted in 1983. “I realized the role would give me the chance to do the sort of thing I’ve never been allowed to do in movies. I mean, I get to disguise myself as a Chinese person, a Skid Row drunk, a gay hairdresser—I wanted to change from leading man to character actor for years now but have never been given the chance before.”

He remained delighted with the series, which spawned a popular live-action show at Universal Studios amusement park, well after it ended.

“It’s the first time I ever had money in the bank,” he said in 1990. “It was a giant boost to my career, and made me a viable actor for other roles.”

Among those roles was that of a World War II British secret service agent in the 1990 television miniseries “Night of the Fox.” He also returned to the stage, appearing in “Love Letters” in London and “The Lion in Winter” in West Palm Beach, Fla., where he met his fifth wife, Laura. Most recently, he appeared in the March 3 episode of the television series “Matlock.”

Born in Detroit, Peppard was educated at Purdue University and the Carnegie Institute in Pittsburgh, then studied at the Actors Studio in New York. In the 1950s, he worked in the Oregon Shakespeare Festival, summer stock in New England, New York-based television dramas and such Broadway plays as “The Pleasure of His Company.”