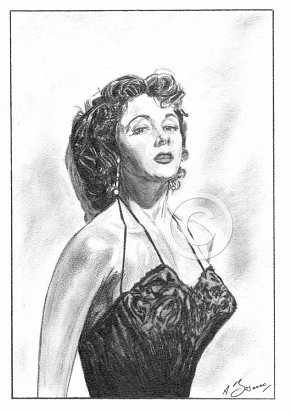

Gloria Grahame

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

In a Lonely Place (1950)

The Bad and the Beautiful (1952)

Recommended reading

Suicide Blonde: The Life of Gloria Grahame (Vincent Curcio)

Written with deep sympathy, stage producer Curcio’s biography evokes Grahame as a beautiful woman and talented actress doomed by her outre behavior.

Although she distinguished herself professionally in such films as It’s a Wonderful Life and The Bad and the Beautiful , Grahame courted scandalous gossip with four unsuitable marriages—one to the son of an ex-husband—and, as an argumentative performer, alienated even admiring directors. She underwent plastic surgery habitually, fixing nonexistent flaws. A trouper, she continued to act until her death from cancer in 198l, at age 57. The author’s memories and quotes from those who knew Grahame combine in a poignant book

Surfing

Gloria Grahame Journal

http://gloria-grahame.journal-of-life.com/#!about

An attractive website with the promise of much to come, but will it deliver?

Comments

Last update: 29/4/16

Gloria Grahame is best remembered today for her awesome femme fatale roles in such classic film noirs as “Crossfire”, “In a Lonely Place”, “Macao”, “Sudden Fear”, “The Big Heat”, “Human Desire”, “The Naked Alibi”, and “Odds Against Tomorrow”. She also featured in Frank Capra’s ‘It’s a wonderful life’ as Violet, the good time girl saved by George Bailey, yet by the mid 60’s her career was confined to supporting roles in television productions.

A turbulent life that ended at the comparatively young age of 57, Grahame was fixated on her looks, undergoing habitual plastic surgery on evidently nonexistent flaws. One such operation would leave her with an immobile top lip, an impediment all too apparent in her latter day roles. Whilst the old maxim ‘If it ain’t broke don’t fix it’, was clearly alien to her, she was nonetheless an excellent actress, if at times a difficult personality to work with.

It was a tempestuous life. Peter Turner, an actor and former lover, authored an account of her last days entitled “Films Stars Don’t Die in Liverpool.” With her career hampered by personal scandal–including four marriages, an affair with her stepson (who became husband number 4), and vitriolic custody battles – Grahame was reduced to treading theatrical boards in England by the mid-70’s. During one of her plays, she met Turner, the couple eventually repairing to New York and California, where they lived together for several years. When they eventually broke up, Turner moved back to England.

On September 29th 1981, he would receive a phone call informing him that Gloria was ill in a hotel in Lancaster. Turner, along with family members, collected Gloria from the hotel and took her to the family home in Liverpool. She had been diagnosed with a huge stomach tumour the year before (earlier breast cancer metastasized to the stomach), but she rejected surgery, insisted she didn’t have cancer and traveled to England to perform on stage. Once in England, a doctor drained fluid from her stomach. Although no one was aware of it, this action perforated her bowel. Gloria was dying. The Turner family nursed Gloria in their home until some of her children arrived to take her back to New York. She would die within three hours of her arrival in the Big Apple aboard a commercial flight. Her condition had dramatically worsened during the flight, the pilot radioing ahead that, according to physicians aboard the plane, Miss Grahame’s death was ‘imminent.’ within three hours of her admittance to hospital, she was gone.

Her GP, Dr. Grace, confirmed at the time that breast cancer had been diagnosed five years earlier, but that Miss Grahame ‘at no time was interested in pursuing aggressive therapy for it.’ The procedure that Dr. Grace offered involved the removal of a body fluid to make his patient more comfortable.

‘She attempted to have the same procedure done in London,’ said Dr. Grace. ‘An infection developed as a result of the procedure.’ Dr. Grace said that Miss Grahame had left the London hospital ‘either against medical advice or she was discharged. Miss Grahame called her children in this country to help her return to New York, where treatment had been successful. It was on the flight to New York that shock resulting from the infection set in and when she got to the emergency room, she was nearly dead,’

It’s an interesting read, ably juxtaposing Gloria’s last days with memories of her relationship with the author in happier times. Principal photography on an EON productions film biopic was due to commence in June 2016 starring Annette Bening in the lead role. Out of print for some time, the book was also due for re-publication at the same time.

Chuck Wilson, writing in the LA Weekly in 2002, offered an incisive précis of Grahame’s life.

Offscreen and on, Gloria Grahame always fell for the wrong man. Married four times, the movie star, whose work is getting a two-week retrospective at UCLA, chose, unfailingly, men who were overbearing, egotistical and, generally speaking, bad news. These personal missteps served her well in front of the camera, where she specialized in portraying women who had learned the hard way to expect the worst from a man, and who knew too that such knowledge was useless in the end, that some kinds of trouble are simply too alluring.

Grahame’s beauty, formed by a lush, voracious mouth and remarkably expressive eyebrows, was unconventional, even disturbing, and MGM, which signed her in 1944, didn‘t know what to do with her. Frank Capra, fortunately, did. Desperate for a “young blond sexpot,” he snagged her for his RKO production It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), in which Grahame, as Violet Bick, the town flirt, was a revelation. RKO quickly borrowed her again for Edward Dmytryk‘s groundbreaking if airless anti-anti-Semitism polemic Crossfire (1947), screening this weekend. Although it’s only a two-scene role, Grahame is unforgettable as a complex dime-a-dance bar girl involved in murder. She received an Academy Award nomination, and while she won the Oscar in 1952, for The Bad and the Beautiful, she lost in 1948, probably because the House Un-American Activities Committee was investigating Dmytryk and producer Adrian Scott, and Hollywood was scared to death.

Around this time, with one bad marriage already behind her, Grahame, at age 24 or 25, became obsessed with what she saw as flaws in her face, particularly her upper lip, which she subjected to a series of cosmetic surgeries that left the lip paralyzed. Mortified, Grahame began stuffing cotton beneath it while filming, to give her mouth a fuller shape. In Suicide Blonde, his invaluable 1989 biography, Vincent Curcio reports that the actress would run to the bathroom between takes to replace the saliva-soaked cotton and reapply the thick layers of lipstick that were her trademark, a practice that drove both cast and crew nuts.

In 1948 she married the gifted maverick director Nicholas Ray, who cast her opposite Humphrey Bogart in the suspense film In a Lonely Place (1950), which opens the UCLA retrospective. This is Grahame‘s most fully realized performance, and the doomed relationship between her devoted-girlfriend character and Bogart’s angry screenwriter has been seen as a reflection of Ray and Grahame‘s turbulent marriage, which by then was on a long, slow slide to hell. Gossip-sheet immortality struck them one summer afternoon in 1951, when the director drove home to Malibu to find Grahame in flagrante (delicto) with Tony, his 14-year-old son from a previous marriage, who’d returned that very day from military school.

Scandal followed scandal, especially after Grahame married Tony nine years later, a move that was heart-driven, ballsy and utterly foolish. Movie work dried up, but by then Grahame already had a rich body of work in the vaults, including her uncompromising turn in Fritz Lang‘s brutal 1953 film The Big Heat (playing Tuesday at UCLA), in which Grahame shoots a woman in cold blood, throws hot coffee in Lee Marvin’s face and somehow remains a tragic heroine. On the opposite end of the spectrum is her deceptively layered, sprightly performance as country bumpkin Ado Annie in Fred Zinnemann‘s 1955 screen rendition of Oklahoma! (screening April 21), although her uncooperative, self-absorbed behavior on the set destroyed what was left of her professional reputation.Surprisingly, she and Tony Ray remained happily married for a time and had two sons, but they finally parted in 1974 after yet another nasty, drama-filled divorce proceeding. Afterward, and before dying of breast cancer in 1981 at age 58, Grahame became passionate about stage acting, in U.S. regional theater and abroad, insisting, even in her final days, that she continue to rehearse for an English production of The Glass Menagerie. Without the last-minute intervention of her children she might well have died there, under the floodlights. That, finally, was the place she’d come to trust the most, where her unpredictable, endlessly daring instincts led not to heartache but to something approaching grace.

It seems incredible that she never faced legal action over her sexual activity with a minor. Commenting indirectly on the relationship years later, Grahame said:

“I married Nicholas Ray, the director. Later on, I married his son, and from the press’s reaction, you’d have thought I was committing incest or robbing the cradle!”

Despite the sense of betrayal, Nicholas Ray wasn’t exactly blameless for his subsequent self-destruction. His sexual relationship with an underage Natalie Wood during the making of “Rebel without a cause,” his problems with drugs and alcohol, his difficulty in completing projects, all hint at a man that was never going to prosecute his ex-wife.