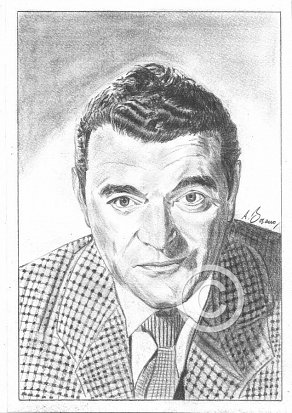

Jack Hawkins

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Mandy (1952)

It is to Hawkins’s credit that he was more concerned with the aesthetics of a role, than the accoutrements of fame.

The film’s director, Alexander Mackendrick, was unconvinced that the role of a Headmaster at a ‘special needs’ school, was a sound choice for anyone seeking movie stardom. Yet, Hawkins clearly felt the role was a good one, and he wanted it for that reason. As his director added; he wasn’t trying to build a persona that would be appealing at the box office.

Interviewed by Barry Norman for his BBC Tv series “The Movie Greats,” MacKendrick added that what distinguished Hawkins among his peers, was an ability to perform with such urgency of belief. He didn’t so much act the role, as totally immerse himself in it. However, unlike Peter Sellers, he didn’t take his character home with him.

More information on the film can be located at:

http://www.antoniobosano.com/film/phyllis-calvert.php

The Intruder (1953)

Benefiting from a new upgraded picture transfer in its original theatrical aspect ratio, this Network 2016 release is an excellent early entry in future Bond director Guy Hamilton’s oeuvre. An engaging, emphatically human drama boasting outstanding performances from Hawkins as a distinguished former officer, and Michael Medwin as the wartime hero he endeavours to save from a life of crime, the movie features strong support from Dennis Price, and George Cole.

http://www.british60scinema.net/films-of-the-50s/the-intruder/

The film – based on Robin Maugham’s novel “Line on Ginger,” attempts to answer the central question: what turns a wartime hero into a postwar thief? As the yarn opens, Jack Hawkins, a former colonel of the Tank regiment, returns to his home to find that a burglar has broken in. The intruder (Michael Medwin) turns out to be a former member of his regiment.

Through a misunderstanding, the thief believes that Hawkins has telephoned for the police and makes a dash for it over the garden wall. From there on, Hawkins is involved in a countrywide search, containing other members of the old regiment in the hopes of their leading him on the right track

http://www.reelstreets.com/films/intruder-the/

The Cruel Sea (1953)

The Long Arm (1956)

Offering up a welcome break from the psychological undertones more prevalent in the ‘noir’ thrillers of its day, Hawkins stars in a superior police procedural drama, with a strong cast, and a loyal, loving wife who supports him throughout. The movie follows a team of British coppers, led by Supt. Tom Halliday (Jack Hawkins), as they attempt to solve a complex case involving a series of burglaries.

Nearly a decade before the introduction of parking meters, there’s a fascinating glimpse of mid 50’s London, suitably bereft of traffic, as our weary detective goes about his duties. Rounded off with a tense finale filmed at the Royal Festival Hall, there’s a hint in the screenplay of the grittier police dramas soon to hit television screens in the early 60’s. Seven years on, it’s a tale already far removed from the world of George Dixon and “The Blue Lamp.”

Short on action set pieces but long on incisive dialogue, the film motors along without overstaying its welcome. Blink and you’ll miss a less than five second appearance from Stratford Johns, who would subsequently find small screen fame as Chief Inspector Barlow in ‘Z Cars’ and ‘Softly Softly’ in the following two decades.

The Two Headed Spy (1958)

A taut wartime spy saga, directed by Andre De Toth, with Jack Hawkins as the Englishman who has been planted by British intelligence into Germany since the end of the First World War. By the time the Second World War breaks out, Hawkins (Major Schottland) has a senior admin job in Berlin, and passes information to his contact, a clockmaker, and then to a popular singer.

The emphasis is on Hawkins’s character and his refusal to become romantically involved with anyone and therefore vulnerable. Kenneth Griffith appears briefly as Hitler, and keen eyed film buffs will spot a young Michael Caine as a Gestapo agent.

Co-starring the tragic Gia Scala, who would die under mysterious circumstances at the early age of 38, the film is short on extended characterisations, yet maintains its plot momentum throughout, thanks largely to Hawkins’ central performance. His outrageous bluff fools even the Fuhrer himself, enabling Schottland to outwit his enemies and supply vital ongoing information to the Allies. Along the way, there remains the omnipresent threat of one Gestapo Leader Müller, played by the ever dependable Alexander Knox.

Undermined by poor distribution and a title more in tune with a sci-fi B movie, the film failed to ignite at the box office – despite strong notices – and is therefore rather overlooked when compared to other wartime releases of the 50’s like “Five Fingers” and “The Man who never was.”

The League of Gentlemen (1960)

Drawing a line under his leading man era, Hawkins would sign off with this huge box office hit about a former army colonel forced into retirement who ropes a cadre of former British army men into aiding him in a one-million-pound bank robbery.

The star-studded cast work well with Bryan Forbes’s multi layered script, which combines the comic caper’s surface humour with a subversive vision of disillusionment. Hand picked for their individual skills-set, this motley collection of avaricious ex-officers retains our sympathy throughout as the risky, multi-tiered plan unfolds to infiltrate a military compound and then rob the bank.

Something of an update on the Ealing tradition, “The League of Gentlemen” marked the debut release of the consortium Allied Film Makers (AFM), combining the former Ealing producer/director partnership Michael Relph and Basil Dearden, as well as Richard Attenborough, Bryan Forbes, Jack Hawkins and his brother. Almost all the AFM partners had a hand in the film, with Relph producing and Dearden directing, while Forbes wrote the script and acted alongside Hawkins and Attenborough. The National Provincial Bank, along with the Rank Organisation, provided much of the group’s backing, which is rewarded in the film with an in-joke: contemplating his leader ex-Colonel Hyde’s bank-robbing plan, ex-Major Race worries, “I do hope he hasn’t the National Provincial in mind. They’re being awfully decent to me at the moment.”

Despite the dark comic tone, sometimes bitter dialogue and the parody of army conventions, the film’s resolution conforms to the moral status quo, with the League’s members each falling prey to the police. As in Ealing’s The Lavender Hill Mob (d. Charles Crichton, 1951), however, there is little sense of justice having been done; our sympathies lie with the rogues, not the police. The League, ultimately, is less a malevolent criminal force than a boys’ club, with its own rules and sense of camaraderie. When, at the end, Hyde sees his League accomplices waiting in the police van, ex-Major Race (Nigel Patrick) offers the respect society has withheld, saluting and informing the ex-Colonel with the customary “All present and correct, Sir.”

Recommended reading

Anything for a quiet life (1973)

Hawkins’ posthumous autobiography, a rather dry, perhaps less insightful work than it might have been, but heartfelt nonetheless. There are acknowledged regrets – his failure as a good husband and father to Jessica Tandy, his first wife and daughter Susan, who disappeared from his life. Professional ambition and youthful inexperience were clearly to blame.

The actor was in denial during the early 60’s, continually working and smoking, consigning his inwardly private fears to a black hole far from the public domain. Courageous on the outside, even if the impetus was derived from, in the actor’s own words, “cowardice pure and simple,” he nonetheless pursued his own vision for the life he had in mind.

At the end of his autobiography his widow, Doreen Hawkins added an emotional post-script covering the period April-July 1973 describing her heart-ache and the final moments surrounding his battle to stay alive:

“I am so cold. We all are. Nick fetched some brandy, and we sipped it between us and comforted ourselves that at least he would not suffer any more, and we would not have to watch his despair and unhappiness. Jack has found his quiet life. Now I have to try and find mine.”

The secret life of Ealing Studios (Robert Sellers) 2015

I was surprised to find this title in my local library as quickly as I did, its appearance coming only weeks after publication.

The first full narrative history of the studio, focusing on its output in the 1940s and ’50s, when the movies made there were in astonishing (and revealing) synchronicity with the national mood. Told through the memories of the people who worked and performed there, ‘The Secret Life of Ealing Studios’ explores how a small group of maverick filmmakers, some of Britain’s most fondly remembered movie stars, and a host of unsung backroom boys and girls created pictures that presented a unique and enduring view of British identity, and which have since become classics. Sellers places particular emphasis on the filming of “Hue and Cry” (1947), “Passport to Pimlico” (1949), “Kind Hearts and Coronets” (1949), “Whisky Galore*” (1949), “*The Lavender Hill Mob” (1951), “The Man in the White Suit” (1951) and “The Ladykillers” (1955), along with war films such as “The Cruel Sea” (1953). At the heart of the story will be the figure of Michael Balcon – perhaps the closest Britain has ever come to producing a movie mogul in the Hollywood mould – and iconic actors such as Peter Sellers, Alec Guinness, Margaret Rutherford and Sid James.

Hawkins himself, merits several mentions, including his near heroic actions in the huge water tank at Denham during studio filming for “The Cruel Sea.” One of the earliest to realise that Donald Sinden hadn’t resurfaced , the quick witted actor dived in and saved his co-star, who would later admit that he couldn’t swim. With the sinking of the Compass Rose now safely in the can, Hawkins was aware that he was involved in some form of career milestone. “We all felt that we were making a genuine example of the way in which a group of men went to war.”

"The Movie Greats" (Barry Norman) 1981

Barry Norman produced several key series on the film industry between the late 70’s and mid 80’s. Interviewed for an Empire magazine 2014 podcast, the film critic and author recounted his formative days.

“I was brought up in a film household because my father, Lesley Norman, produced The Cruel Sea and directed Dunkirk and various other films, so there were always actors coming in and out of my house. I learned very early on that they’re probably prettier than the rest of us, but they’re very much working stiffs like we all are, with the same kind of problems. They talked to my dad about whether they had enough money to pay their income tax or whether their wife was having an affair or whether their career was on the way up or the way down, and they had all the same worries as everybody else. So I then realised early on that there was no point in being awestricken by somebody who made a living by pretending to be somebody else. The closest I came to being starstruck was by Laurence Olivier, but that was largely because of what he did in the theatre rather than the cinema.”

Under construction

Comments

Last update : 06/05/2018

There comes a point in time when every student of the second World War sits down to watch Charles Frend‘s 1953 classic, “The Cruel Sea”. The film is a triumph as an unsentimental depiction of the ugly realities of war at sea, the hardships endured by the serving crews, their roller-coaster emotions and their pride in mission accomplishment. In the film, Captail Ericson is portrayed by Jack Hawkins, truly one of the most loved British actors of all time.

As the film critic Paul Page so aptly put it:

“His face, cut from British stone, is to many, the face of the golden age of British cinema.”

In 1966, cancer of the larynx would destroy his distinctive voice, but not his desire to continue acting. A victim of his own 3 pack a day habit, I well remember hearing him interviewed after his voice box had been fitted. He would appear in films right up until his death, his dialogue dubbed in post-production by either Charles Gray or Robert Riett.

His continuous work schedule, though limited to cameo roles, spoke volumes for the deep affection in which he was held by so many industry people.

Hawkins was born in north London in 1910, the son of a furniture-maker. He made his first professional appearance on stage at the age of 12, in a pantomime, and appears to have been a natural. He spoke in later life of the instant thrill and excitement of being on stage. By 18, he was appearing on Broadway, and by 20, he was in films.

One of his misfortunes was to have to deal with the British film industry both in its amateur-hour phase in the 1930s (when, despite his considerable talent, he could do no better than playing bright young men in a few dreary and deservedly unremembered films) and in its steep decline in the late 1950s, when he was wasted on various projects. In the 1930s, he earned most of his living on the stage, and it was probably just as well: it meant that by the time the British film industry was properly ready for him, he had developed skills that would make him the most successful and popular British film star of his generation.

Hawkins volunteered for the Army in 1940. By 1944, he was a colonel running the ENSA operation in India, ensuring that there was entertainment for the troops and developing the careers of countless others who would become household names over the following 20 years. This experience might have diverted Hawkins into the life of an impresario, but the lure of the stage was too much for him. Also, when he was to incarnate the officer class in the 1950s, he would be doing so from a position of experience rather than out of his imagination.

Under construction

The larynx is another name for the voice box. It is a tube about 2 inches (5cm) long in adults. It sits above the windpipe (trachea) in the neck, and in front of the food pipe. The food pipe in the upper part of the neck is called the pharynx. The larynx protects your windpipe during swallowing, allowing the air you breathe in to reach the lungs. It produces sounds for speaking and is the place in your body where the breathing and digestive systems separate. When you breathe in, air travels through your mouth, larynx, windpipe (trachea), and then into your lungs.

During the act of swallowing, part of the larynx called the epiglottis closes tightly over your airway. This flap of cartilage stops food and saliva going into your lungs. When the epiglottis is closed, food and drink can go down your food pipe (oesophagus) and into your stomach. Problems occur when people continue talking (inhaling) whilst eating, and a particle of food travels down the trachea instead of the oesophagus. The other potential problem is more anatomical. You swallow food and the epiglottis doesn’t fully close over. Only a minute amount of food is necessary to cause enormous problems.

The vocal cords are two bands of muscle that form a V shape inside the larynx. These vibrate together when air passes between them. This produces the sound of your voice.