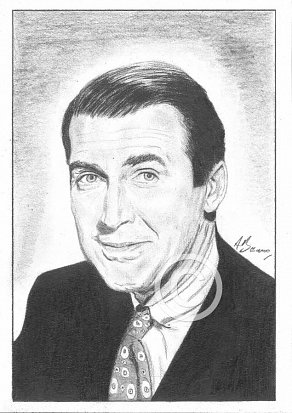

James Stewart

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

Desert Island Discs (Broadcast : 17/12/83)

At the time this radio programme was made, James Stewart, with his inimitable slow drawl and gangly walk, had been making films since 1935, from ‘The Philadelphia Story’ to ‘The Far Country’ and ‘Mr Hobbs Takes a Vacation.’ In conversation with the show’s creator, Roy Plomley, he talked about his long career and chose the eight records he would take to the mythical island.

1.Kenneth McKellar – On The Road To Mandalay / 2.The Glenn Miller Orchestra – Moonlight Serenade / 3. James Stewart Rolling Stone (Artist: Henry Fonda With Orchestra) / 4.Gordon Jenkins & His Orchestra – Don’t Cry, Joe / 5. The Norton Singers – There, I’ve Said It Again / 6. Ella Fitzgerald – I’ve Got A Crush On You (Artist: Nelson Riddle and his Orchestra) / 7.Jo Stafford & The Starlighters – Ragtime Cowboy Joe /8. The Pied Pipers – Dream

The programme survives in the BBC archives.

Recommended viewing

Mr Smith goes to Washinton(1939)

It may have courted controversy with its jaundiced view of the US Government and its inner workings but the film also depicted traditional American values of patriotism and faith in human nature and provided an educational lesson in the passage of Bills through Congress.

Stewart broke through as a leading actor with this film, the one he is perhaps most identified with, thanks to Capra’s deft direction and his portrayal of a naive, idealist, patriotic young politician who, after being sent to Washington as a junior senator, matures in wisdom to fight political corruption within his state’s political machine, and guards American values as a moral hero. It set the template for much of his screen characterisations, and was a box office success with the public.

It’s a Wonderful life (1946)

The road to enlightenment can be a tortuous one. I know people who have never seen this movie and would dismiss it as mawkish sentimental nonsense if they did. It takes all sorts to make this world. My wife bought me the DVD a few years back and then subsequently gave me the superbly colourised version. Prior to all all of that I had owned the film on videotape. It’s a perennial fixture in our house at Christmastime and the lump in my throat at the film’s finale grows with each passing year.

Harvey (1950)

Elwood P. Dowd (Stewart) is a middle-aged, amiable and somewhat eccentric individual whose best friend is an invisible 6’ 3.5” tall rabbit named Harvey. As described by Dowd, Harvey is a pooka, a benign but mischievous creature from Celtic mythology who is especially fond of social outcasts like Elwood. Elwood has driven his sister and niece, who live with him and crave normality and a place in “society”, to distraction by introducing everyone he meets to his friend, Harvey.

His family seems to be unsure whether Dowd’s obsession with Harvey is a product of his (admitted) propensity to drink or perhaps mental illness. Elwood spends most of his time in the local bar, and throughout the film invites new acquaintances to join him for a drink (or to his house for dinner). Interestingly, the barman and all regulars accept the existence of Harvey, and the barman asks how they both are and unflinchingly accepts an order from Elwood for two Martinis.

As Elwood puts it himself: Harvey and I sit in the bars… have a drink or two… play the juke box. And soon the faces of all the other people they turn toward mine and they smile. And they’re saying, “We don’t know your name, mister, but you’re a very nice fella.” Harvey and I warm ourselves in all these golden moments. We’ve entered as strangers – soon we have friends. And they come over… and they sit with us… and they drink with us… and they talk to us. They tell about the big terrible things they’ve done and the big wonderful things they’ll do. Their hopes, and their regrets, and their loves, and their hates. All very large, because nobody ever brings anything small into a bar. And then I introduce them to Harvey… and he’s bigger and grander than anything they offer me. And when they leave, they leave impressed. The same people seldom come back; but that’s envy, my dear. There’s a little bit of envy in the best of us.

I have known a man like Elwood P. Dowd. Whilst spending time in Gibraltar as a young man with my father’s family he would take up his position at the end of Main Street as a traffic policeman and all the residents of the rock would follow his instructions. It did not matter if they were running late for they would pull up, place their cars in nuetral, apply their handbrakes and wait for his signal to continue on their journey. During the wintertime he would turn up with a red cape to entertain the residents with a mock bullfight and the crowds would cheer him on with every imaginary feat of daring. I used to observe and encourage him in everything he did. Perhaps tolerance of such eccentricities can only be found in small communities but in ‘obliging’ him what were we all saying about ourselves? I wonder to this day.

As this marvellous film progresses, everyone is certain that Elwood has finally lost his mind yet Harvey’s presence begins to have positive effects on the townsfolk, with the exception of Elwood’s own sister Veta who, ironically, can also occasionally see the white rabbit. A snooty socialite, Veta is determined to marry off her daughter, Myrtle to somebody equally respectable, and Elwood’s lunacy is interfering. When Veta attempts to have Elwood committed to an insane asylum, matters go awry and she is accidentally admitted instead of her brother. Subsequently the institution’s director, Dr. Chumley, begins seeing Harvey, too.

At one point, when her daughter asks how someone could possibly imagine a rabbit, Veta says to her “Myrtle Mae, you have a lot to learn and I hope you never learn it”.

Matters continue in a suitably haphazard fashion before Elwood, along with everybody else, arrives back at the hospital. By this point, Dr. Chumley is not only convinced of Harvey’s existence, but has begun spending time with him on his own, with a mixture of admiration and fear.

Priceless movie making; watching for the first time and realising that no attempt utilising special effects would be made by the film crew, I began to see Harvey myself.

If you don’t ‘get it’ then you don’t have an ounce of sentimentality within you.

Rear Window (1954)

The terrible incompatability of male/female positions as they have both been defined and evolved in our culture. The man’s viewpoint is one thing, the woman’s is always another. They argue and with all this is the idea of romantic love – what Miss Lonely hearts is longing for, what the newlyweds are expecting, what Lisa (Grace Kelly) wants. Hitchcock’s view of romantic love is extremely sceptical to say the least and as Stewart’s voyeurism leads him to uncover murder he must deal with his temporary incapacity, his beautiful fiancee – the embodiment of perfection, and how the last half of his life is to ‘play out’.

Vertigo (1958)

Perhaps a little too grizzled for such a relationship, Stewart’s performance as a prototype stalker is especially troubling as we watch his soft features harden and his wholesome persona become mangled and corrupted by romantic manipulation. “If I let you change me, will you love me?” asks the soon to be reborn Madeleine character; little wonder the writer David A Cook said of the film that it “suggests not only the fraudulence of romantic love, but of the whole Hollywood narrative tradition that underwrites it.”

http://www.guardian.co.uk/film/2012/aug/01/vertigo-film-critics-top-10

Stewart is nevertheless superb, sacrificing some of his genial screen presence to play the neurotic, obsessed Scottie. He is cold to his longtime friend and onetime fiancé, Midge (Barbara Bel Geddes); too forceful and urgent with Madeleine; and downright cruel in his attempts to make over the crude and world-weary shop girl Judy (also played by Novak) into the elegant, mysterious Madeleine. Once alerted to the subterfuge his demeanour hardens; perhaps it was after all, obsessive infatuation rather than real love. Either way, the affair nearly destroys him.

Anatomy of a murder (1959)

Whilst the overall end product cannot match the sum of its individual parts, (the Duke Ellington score, a strong supporting cast) the film ultimately holds together despite its numbing 2 hour 40 minutes running time.

On the cusp of the swinging sixties, the film’s monochrome imagery contrasts with its colourful themes – explicit sex and lawyers triumphing by guile, stealth and trickery.

Lee Remick is the vamp any man can have the misfortune in meeting and marrying whilst Eve Arden, Arthur O’Connell and George C. Scott all contribute strong suppoting performances. Holding it all together is James Stewart playing the part of a small-town Michigan lawyer who takes on the difficult case of defending a young army lieutenant (Ben Gazzara) accused of murdering a local tavern owner who he believes raped his wife (Lee Remick).

The Flight of the Phoenix (1965)

The veteran stunt flyer Paul Mantz lost his life filming the take off scene, an unthinkable event in this modern world of CGI laden movies.

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Paul_Mantz

“The Flight of the Phoenix”, based on the Elleston Trevor novel, has little more than one set and no costume changes; and the action is confined to the few yards around an airplane crashed in the desert. Yet its story is more gripping than most “action” movies. That it should have been remade in the 21st century with Denis Quaid in Stewart’s role is one of the great mysteries of moviedome for it pales in comparison.

An oil company plane crashes at the hands of a crusty old pilot (James Stewart) whose bitterness and fatalism are brought to the fore when he’s forced to admit the crash was due to pilot error. Having contributed to the enormity of the problem with his wayward navigation, the semi-alcoholic Richard Attenborough, in a supremely understated performance, becomes the mediator between the rancorous passengers and crew. The motley group includes a company accountant (Dan Duryea); a shell-shocked employee (Ernest Borgnine, by turns touching and silly) sent home in the company of his doctor (Christian Marquand); a straight-laced British officer (Peter Finch) and his mutinous sergeant (Ronald Fraser); several oil company employees, including one (Ian Bannen), who is always making vicious jokes at the expense of the others and a German “designer” (Hardy Kruger) who went to the oil fields to visit his brother.

Stranded in the desert with no hope of rescue, they debate various schemes for salvation, all of which fail, until Kruger tells the others he is an airplane designer and he has discovered a way to build a new plane from the spare parts of the old one. All it needs for is a handful of unskilled men, living on strict water rations and no food but pressed dates, coping with unbearable heat during the day and unbearable cold at night, to transform themselves into aircraft manufacturers before they all succumb.

The major tension is the confrontation between Stewart’s old-school pilot and Kruger’s technologically self-righteous engineer; at one point, Stewart’s character makes the incredibly prescient remark that one day the little men with their slide-rules and computers will inherit the earth.

Well into the morale boosting construction project a tripartite meeting between Stewart, Kruger and Attenborough reveals that the German’s expertise extends only to the field of model gliders, which whilst admittedly capable of legitimate flight, does challenge the designer’s previously tacit credentials. Stewart’s reaction shot “My God Lew, he’s a toy aeroplane maker” is priceless, his weatherbeaten unshaven features only adding to the absurdity of their position now unfolding more redolently before his very eyes. Facing certain death, Kruger storms off to tend his bruised ego, Stewart stews and festers, neither man capable of any form of rapprochement whilst Attenborough looks on with incrudulity that matters have come to this. Peerless moviemaking and in my opinion, certainly one of the fifty greatest scenes ever filmed.

Recommended reading

Jimmy Stewart : The Truth Behind The Legend (Michael Munn) 2006

There is sufficient anecdotal evidence to support the commonly held view that Stewart was a really nice guy; an attribute he conveyed in so many of his movies and a key factor in his universal appeal.

Yet he had a temper, and whilst perhaps not overtly rascist, was uncomfortable around negroes. The son of a Pennsylvanian store owner, he was perhaps, rather typical of his fellow countrymen. In his quiet, racially homogenous hometown of Indiana, American blacks were as rare as Eskimos. The same applied to his exclusive boarding school, and his university, Princeton. He would remain sufficiently wary and suspicious of black Americans to the point where the black actor Woody Strode, who appeared with him in John Ford’s western, “The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance,” accused him of racism. Others felt that his attitude to Jews, as well as to blacks, was hostile enough for the racist tag to be applied to him.

We should, perhaps, place his attitudes and beliefs within the context of the era in which he grew up. His upbringing, and church beliefs, saw an almost subliminal belief in the superiority of whites. He was never openly rude, or dismissive of the negroes he met, but it was obvious that these encounters made him uncomfortable.

Not surprisingly, given his deeply felt patriotism and his conservative attitudes to social issues, he became a staunch Republican, and an admirer of the right-wing head of the FBI, J Edgar Hoover. His support went beyond mere admiration, acting as Hoover’s informant, filing reports on the criminals he saw infesting Hollywood. Unware of Hoover’s compromised position as a closet homosexual, he would remain constantly baffled by the FBI director’s indifference to the mafia, and the reports he studiously prepared.

He enjoyed his bachelorhood in Hollywood, yet remained true to Gloria, his wife of forty years. She, in turn, encouraged his monogamy by often being ‘on-set’ with him when he was filming.

Comments

Last update : 9/8/15

“I don’t want to get married — ever — to anyone! You understand that? I want to do what I want to do.”

Ben Okri, the Nigerian poet and novelist wrote : “We plan our lives according to a dream that came to us in our childhood, and we find that life alters our plans. And yet, at the end, from a rare height, we also see that our dream was our fate. It’s just that providence had other ideas as to how we would get there. Destiny plans a different route, or turns the dream around, as if it were a riddle, and fulfills the dream in ways we couldn’t have expected.”

The frustrated character is George Bailey, the film is “It’s a Wonderful Life,” and the man who played him would define his screen persona in the role. Commenting on his death President Bill Clinton was moved to say that : “America lost a national treasure today. Jimmy Stewart was a great actor, a gentleman and a patriot.”

George Bailey has spent his entire life giving of himself to the people of Bedford Falls. He has always longed to travel but never had the opportunity in order to prevent rich skinflint Mr. Potter from taking over the entire town. All that prevents him from doing so is George’s modest building and loan company, which was founded by his generous father.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/12/19/movies/19wond.html?pagewanted=all

http://www.contactmusic.com/news/its-a-wonderful-life-tops-christmas-movie-list_1266237

Stewart married at forty one years of age, and was perhaps reticent to commit until his military service was completed. By all accounts, the marriage was a contented and enduring one, although the loss of his stepson during the Vietnam war was a huge blow.

Stewart was a distinguished bomber pilot serving on active duty during World War Two. The following website commemorates his exploits.

http://www.danielsww2.com/JimmyStewart.html