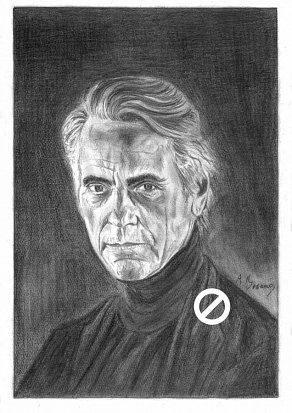

Jeremy Irons

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Munich - The Edge of War (2021)

The Netflix historical drama Munich: The Edge of War tells a story any history student is eminently familiar with: the last days before World War II. As Hitler rose to power and began his march across Europe, British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain made a last-ditch effort to avert the conflict. His attempts to avoid another global conflict led to his historical reputation as a coward whose attempts to appease Hitler only emboldened him, allowing Germany to consolidate power.

But Munich takes a much more sympathetic approach to Chamberlain, painting a portrait of a man desperate to protect his beloved home from the ravages of another world war. It’s a portrayal that has some basis in history, even as the film strays elsewhere.

Chamberlain (played by Jeremy Irons) is the film’s central figure, but not its main character. That role falls to Hugh Legat (1917’s George MacKay), a young diplomat in the prime minister’s office who becomes caught up in a desperate German attempt to depose Hitler before war can begin in earnest. On the other side of this plot is Paul von Hartmann (Jannis Niewöhner), a former Oxford classmate and repentant Nazi. Von Hartmann has come into possession of a German memo that lays out a far wider military expansion than the Allies are expecting. He contacts Legat in the hopes that the document will be able to convince Britain to declare war, allowing dissenting German generals to remove Hitler from power.

While Legat and von Hartmann are fictional characters — the creations of speculative history novelist Robert Harris — the situations around them are largely based in reality.

The Munich accords, held in September 1938, are regarded today as a shortsighted pit stop along the road to World War II. Chamberlain was there, as were Hitler and a small army of diplomats. And a group of high-ranking Nazi officials really did plan to overthrow Hitler if he followed through on his threat to declare war on Czechoslovakia, although it remains unclear just how far the plot really reached. Von Hartmann’s almost-assassination as depicted in the film certainly did not occur (although plenty of similar attempts on Hitler’s life failed).

That the British government was warned of Hitler’s ultimate intentions also has its basis in history: Upon reading Mein Kampf, ambassador to Germany Sir Horace Rumbold wrote to the foreign office that “Hitler’s foreign policy may be summed up as the destruction of the peace settlement and re-establishment of Germany as the dominant Power in Europe.” Still, peace talks proceeded.

Munich ends on a subdued note, with von Hartmann’s attempt to kill Hitler foiled and war closer than ever. But it also reclaims a notorious part of Chamberlain’s history as prime minister: his triumphant return to Britain after securing an agreement with Germany. Fresh off the plane, Chamberlain declared “peace for our time,” a phrase that would take on a heavily ironic significance in the years to come. Eleven months later, Britain was at war.

The perspective Munich puts forth — that Chamberlain’s policies of appeasement were a necessary stopgap that helped England prepare for war when it did eventually come — is one that has gained momentum with historians in recent years. Britain lacked powerful allies, a prepared military and, most of all, a committed and passionate public. In the film, Chamberlain is met upon his return from Munich by crowds of people cheering the renewed peace. To ask them to go to war over the obscure and distant borders of Czechoslovakia would have been a difficult errand for any political leader. As to whether Chamberlain really displayed the self-sacrificing mentality he does in the film (“If I’m made to look a fool, well, it’s a small price to pay,” he tells an advisor), that’s a question history has yet to answer.

One aspect of Irons’s superb characterisation which is not emphasised was the class divide between the two leaders. ‘The commonest little dog I have ever seen.’ These were British Prime Minister’s Neville Chamberlain’s snobbish observation after he first met Adolf Hitler in September 1938 in a desperate attempt to avert war in Europe. Chamberlain also described Hitler as ‘entirely undistinguished. You would never notice him in a crowd and would take him for the house painter he once was.’

Comments

Last update : 21/7/24

Jeremy John Irons is an English actor and activist. He is known for his roles on stage and screen having won numerous accolades including an Academy Award, two Golden Globe Awards, three Primetime Emmy Awards, and a Tony Award. He is one of the few actors who has achieved the “Triple Crown of Acting” in the US having won Oscar, Emmy, and Tony Awards for Film, Television and Theatre.

Irons received classical training at the Bristol Old Vic Theatre School and started his acting career on stage in 1969. He appeared in many West End theatre productions, including the Shakespeare plays The Winter’s Tale, Macbeth, Much Ado About Nothing, The Taming of the Shrew, and Richard II. In 1984, he made his Broadway debut in Tom Stoppard’s The Real Thing, receiving the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play.

His first major film role came in The French Lieutenant’s Woman (1981), for which he received a British Academy Film Award nomination for Best Actor. After starring in dramas such as Moonlighting (1982), Betrayal (1983), The Mission (1986), and Dead Ringers (1988), he received the Academy Award for Best Actor for his portrayal of Claus von Bülow in Reversal of Fortune (1990). Other notable films include Kafka (1991), Damage (1992), M. Butterfly (1993), Die Hard with a Vengeance (1995), Lolita (1997), The Merchant of Venice (2004), Kingdom of Heaven (2005), Appaloosa (2008), and Margin Call (2011). He voiced Scar in Disney’s The Lion King (1994) and played Alfred Pennyworth in the DC Extended Universe (2016–2023) series of films.

On television, Irons’s break-out role came in the ITV series Brideshead Revisited (1981), receiving nominations for the British Academy Television Award and Golden Globe for Best Actor. He received a Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actor in a Limited Series or Movie for his performance in the miniseries Elizabeth I (2005). He starred as Pope Alexander VI in the Showtime historical series The Borgias (2011–2013) and as Adrian Veidt / Ozymandias in HBO’s Watchmen (2019).