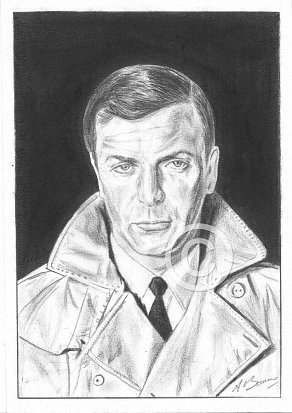

Michael Caine

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

Desert Island Discs - BBC Radio 4 (20/12/09)

Recommended viewing

The Ipcress File (1965)

Harry Saltzman’s antidote to 007’s murderous exotica was a perfect vehicle to launch Caine as a fully fledged British star. The leading character, a British army sergeant arrested for black marketeering and seconded to MI6 as a counterintelligence agent, becomes embroiled in a fictitious slant on Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s ‘Brain Drain’ as Radcliffe becomes the latest in a string of scientists to be kidnapped, along with a top secret file. Caine’s Harry Palmer is pitched into a world of grimy brutalism, mundane bureacracy and the vividly realistic, morally-empty, quotidian horror of Cold War espionage.

Sidestepping the obligatory L101 field reports, Palmer’s gunning for a pay rise to buy a new infra- red grill and, ever the aspiring gourmet, is content to stock up on more expensive tin labels, much to the dismay of Colonel Ross (Guy Dolman), his budget conscious boss.

Sidney J. Furie’s directorial work, much maligned at the time, adds a surrealistic sheen to the film’s gritty landscapes whilst Nigel Green, as Dalby, is duplicitous and imperious in equal measure.

The film spawned four sequels but only ‘Funeral in Berlin’ comes close to matching the pace and inventiveness of this groundbreaking espionage thriller.

http://keesstam.tripod.com/deleted.html

Funeral in Berlin (1966)

Infinitely more bogged down with plot overload this time around, our bespectacled anti-hero is sent to West Berlin to suss out one Colonel Stok (Oskar Homolka), the head of intelligence in the Soviet Union’s Berlin section, and the man responsible for preventing escapes over the Wall. Ostensibly seeking to defect, Palmer must determine if the colonel’s offer is genuine. Along the way, he is reunited with Johnny Vulkan (Paul Hubschmid), with whom he previously ran a black market operation in the city. Johnny is fond of Harry, and Hubschmid’s reaction shot in a local bar when Caine displays his less than encyclopaedic knowledge of the german language is priceless. Approached by a waiter with the customary felicitation “Bitte mein herr?” our beleagured agent responds most earnestly, “No – make mine a light brown!”

No sooner has he got his man tagged and ready for shipping back to London, than a beautiful model slips into his taxicab and before Harry can draw breath, he’s knee high in Israeli operatives hot on the trail of war criminals, and a deceptive British control in Berlin.

Guy Hamilton directs with pace, and the film boasts an attractive travelogue sheen. Harry’s relationship with his superior Colonel Ross (Guy Doleman) remains as testy as ever, and the movie is wholly representative of the more underrated thrillers of its period. The cinematography, redolent with images of 60’s Berlin, remains a timeless reminder of a country then twenty three years from reunification.

I hadn’t seen the film for over forty years – my only recollection being the early daring escape over the wall – but a surprise reshowing on TCM in the fall of 2014 was a most welcome opportunity to revisit Caine’s second outing as Len Deighton’s reluctant spy, and to reappraise the rather convoluted plot.

Alfie (1966)

There was always something about Alfie, a cockney lothario who treads the fine line between amorality and sexism. Barely old enough to fully understand his exploits when I first saw the film, it was still obvious to my young eyes that he was ultimately a loser. As my father put it to me when the film was over – “Do you think you were put on this earth solely to have a good time?” A hugely entertaining movie, it is nonetheless both a minor British classic and a valuable record of the hedonistic Swinging 60s.

The role of womanising cad Alfie Elkins fit the 33-year-old Londoner like a glove and earned him his first Oscar nomination, though on the night he lost out to Paul Scofield in “A Man For All Seasons”. (Alfie was nominated in five categories in all, but failed to take home a single award.)

Based on the play by Bill Naughton, Lewis Gilbert’s film broke new ground by interspersing its amorous anti-hero’s sexual conquests with frank and witty confessionals, delivered straight to camera. Such is Caine’s ease in front of the lens that this inherently theatrical device works beautifully on-screen, especially when Alfie begins to query the value of his rootless, carefree existence.

Viewed from a post-AIDS perspective, Alfie’s dalliances with brassy Millicent Martin, mousy Jane Asher, and vulgar American Shelley Winters seem positively suicidal. But Alfie’s casual promiscuity is not without repercussions, and the most powerful sequence comes when he is forced to arrange an illegal abortion for one of his mistresses. Denholm Elliott’s compelling performance as a seedy, backstreet abortionist and Vivienne Marchant’s ashen complexion provide the catalyst for Alfie’s moral awakening. If there’s truly a price to pay for one’s actions, then the sight of our favourite Londoner looking on from afar at his only son’s christening is a salutary reminder for us all……………

http://www.reelstreets.com/index.php/component/films/?task=view&id=17&film_ref=alfie

Educating Rita (1983)

Hannah and her sisters (1985)

The Cider House Rules (1999)

Recommended reading

Michael Caine - A Class Act (Christopher Bray) 2005

Overlooking ‘the turkeys,’ and God knows there’s been more than enough of them, Bray focuses instead on some of Caine’s most compelling film entries, to paint a meritorious picture of one of Britain’s most pre-eminent actors.

Born into south London poverty during the depression-hit Thirties, Caine suffered the depredations of War as a child and wasted his energies fighting in Korea during the Fifties. Subsequently, he began his long, slow climb up the greasy pole of the acting profession with walk-ons and bit parts. As the old order began to crumble in the early 60’s, BBC clipped accents began waning and regional dialect became ‘sexy.’

Caine’s working class origins came into their own and iconic roles would follow one after the other: the old Etonian who no longer quite believes in his power to command in ‘Zulu;’ Harry Palmer in ‘The Ipcress File;’ ‘Alfie;’ ‘The Italian Job.’ He summed up the grit of the Seventies with ‘Get Carter,’ the get-rich-quick glitz of the Eighties with ‘Mona Lisa,’ and was the living embodiment of John Major’s vaunted ‘classless society’ of the Nineties – a truly world-class British movie star.

Within its clearly defined limitations – namely Caine’sprofessional career – Bray’s account is full of splendid left-field insights without ever really getting successfully under his subject’s skin. About that intervening dross – and there’s a famously high quotient of it – Caine himself has always been amusingly up-front. Of ‘Jaws: the Revenge’ (1987) he said: “I haven’t seen the film, but by all accounts it is terrible. However, I have seen the house that it built, and it is terrific.” Bray twice refers to the movie as “no masterpiece,” which is over respectful to say the least. Yet movies like this and others – ‘The Island’, ‘the Swarm,’ ‘Ashanti,’ lie at the very heart of the conundrum that is Caine. Whilst directorial mis-management and post production flaws can seriously undermine any gold plated screenplay, certain scripts have sufficient dross written all over them to ward off any actor seriously interested in his ‘art.’ Agent Denis Selinger’s advice to “take whatever comes along – there’ll always be the occasional great part” – was clearly well intentioned, but some restraint would have done no harm at all. Like a Samuri warrior flaying around in a desparate search for his sword, Caine, on occasions, seemed hell bent on destroying any credibility he had striven so hard to attain. It’s this practical ‘working man philosophy’ towards money that has so incensed some of his more highfalutin contemporaries. The British press would crucify him………………………

Comments

Last update: 8/5/17

In 1992, Michael Caine published “What’s It All About?”, a rather engaging autobiography, in which he described how a hardscrabble childhood in the South London project called the Elephant and Castle had turned into an unexpectedly successful, sometimes brilliant career. Approaching 60 at the time, and suspecting his acting days were behind him, his light and lively retrospective was brisk and entertaining, rapidly becoming a bestseller.

Then came the surprise of the next 18 years, into which Caine packed 35 more films, an occasional turn on TV, earned an Oscar for “The Cider House Rules” in 2000 and a nomination for “The Quiet American” in 2003. A sequel “The Elephant to Hollywood”, was published in 2011, yet despite his impressive work of recent times with a new generation of actors and directors, the book remains preoccupied with his distant past. Frankly, at the risk of being brief, blunt and extremely unkind, I found it a godawfal yawn, redolent with bonhommie and amusing anecdotes, yet with precious little insight into what makes Maurice Micklewhite truly tick. Apparently, after more than half a century in the business, we’re asked to believe that the actor remains nonplussed at his movie stardom. I couldn’t even complete one whole chapter. Thank God the version I skimmed over was a library title – the thought of even a £2 charity shop purchase would have sickened me.

Infinitely more readable is Christopher Bray’s biography : Michael Caine – A Class Act’ (Faber 2005). I managed to obtain an ex-library stock copy for £1.29 complete with a clear dust jacket. A clue to the actor’s work ethic and personal drive is offered on the back cover with the apocryphal comment :

‘When somebody says to me, “I’m proud to be cockney,” I say, “What else are you proud of? What do you do?’

It reads well but is somewhat compromised by Caine’s varying attitude to film projects. After receiving his knighthood, the actor was quoted as saying that he would not open mail that failed to address him by his correct title. Refuting this statement with an ear to ear grin, Roger Moore made it clear that this was unlikely as his friend couldn’t take the risk of missing a cheque in the post!!! Such pretentiousness is somewhat at odds with Caine’s personality, for whilst he has aspired to ‘high art’ in some of his most notable portrayals, he has also never been averse to the material rewards of a mere ‘jobbing actor.’ By his own admission, some of his best pay days have come via cinematic ‘stinkers’ – ‘The Island,’ and ‘Jaws 4’ – The Revenge’ are two entries that readily spring to mind. Then there’s ‘Escape to Victory’ in which dear Michael fails to convince as John Colby, former West Ham and England soccer star, now detained at Germany’s pleasure as a WWII POW. Having defied the grim reaper several years earlier, Caine was keen to work with John Huston again, duly signing on for a piece of pure escapism, in which his personally selected XI take on an elite German team in Paris. The escape committee cannot overlook the possibilities of a break out, as tensions rise both before and during the exhibition match. It’s all nonesense but entertaining fluff nonetheless. With an all star soccer cast including Pele, Moore and Ardiles, Max Von Sydow as the sympathetic Von Steiner, and Anton Diffring as the match commentator, there’s always more than enough to savour if you’ve leapt aboard for the rollercoaster ride.

There’s an appealing bonhomie about Michael Caine, but it hasn’t cut mustard with everyone. Despite the gut wrenching lauditories actors are wont to heap upon each other, he has nonetheless been capable of upsetting several of his contemporaries. In a curious interview with The Sunday Times in 1995, for example, Caine described Richard Burton, Peter O’Toole and Richard Harris as “drunks” and then allegedly added, a trifle tastelessly, “but at least it takes 30 years to kill you.” The late Richard Harris would respond, infamously describing him as “an over-fat, flatulent, 62-year-old windbag. A master of inconsequence masquerading as a guru, passing off his vast limitations as pious virtues.”

Heavy drinkers, if not alcoholics, invariably view themselves as seafarers on some heroic journey to self enlightenment, battling their demons along the way, whilst toying with death like a tight rope artist. I recall Michael Parkinson on his 1974 BBC chat show, sitting in hushed reverence as Richard Burton recounted the tale of a three day bender that had brought him close to oblivion. The episode was described in a manner more befitting of a hardy mountaineer, trapped at 3,000 feet for several days without essential supplies, the inclement weather worsening by the hour. I wonder how the actor would have responded had Parkinson queried his difficulties in reconciling such self destructive behaviour with an exceptionally well read individual, a man still capable of commanding large fees for his services, and a person still highly attractive to the opposite sex. Whilst alcoholism is today clinically recognised as a disease, it is still nonetheless a way of life that drives wedges between individuals who might ordinarily have been the best of friends. Caine had to contend with Ian Hendry’s aggression on the set of ‘Get Carter’ in the summer of 1970, as the combination of drink and professional jealousy threatened to spill over into the daily shooting schedule. It is not unrealistic to assume that he has dealt with similar scenarios throughout his career, and this leads me onto one of the unspoken elements of social life; namely the attitude of non-drinkers towards those who do habitually imbibe.

http://www.succeedsocially.com/avoiddrinking

http://livingsobersucks.com/blog/2014/10/21/the-changing-perspective-of-a-non-drinker-102114/

under construction

No less a luminary than Joan Littlewood, the founding mother of working-class theatre in Britain, once told the young Caine after only one production: “Piss off to Shaftesbury Avenue. You will only ever be a star.” Clearly, not everyone has warmed to him – Dirk Bogarde, as he made it perfectly clear in his autobiography, could not stand his speaking voice.

It was not a rare occurence in the 70’s and 80’s to overhear the actor himself, bitterly bemoaning the lack of respect he’d received to date in his own country. Where the Americans had awarded him two Oscars and major star status, the British, he would complain, STILL didn’t feel he could act. Maybe he’d been away for too long, his tax exiles in Hollywood and the south of France keeping him from true Brit popular opinion. Then suddenly, his native homeland fell in love with him. Suitably enamoured with his exceptional performance as Ray Say, the low-life cockney loser in ‘Little Voice’ (1998) – the British psyche loves the high and mighty brought down low, and Caine was content to undermine his celluloid image – they were happy to drag out and dust off his earlier work. ‘The Italian Job’ – “You were only supposed to blow the bloody DOORS off” was now reappraised as classic comedy-action, ‘Get Carter’ – “You’re a big man but you’re out of shape, with me it’s a full-time job. Now behave yourself.” – was raised from gritty cultdom, and ‘The Man Who Would Be King’ would finally be accepted as the epic adventure it always was. Add to the mix his toffee-nosed upstart in ‘Zulu,’ the original Harry Palmer trilogy, his washed-up professor in ‘Educating Rita,’ his hardcore duel with Laurence Olivier in ‘Sleuth,’ his laudanum-addicted doctor in ‘The Cider House Rules,’ his sketchy adulterer in ‘Hannah and Her Sisters’ and, of course, ‘Alfie,’ there was no way even the most iconoclastic Brit would argue that Michael Caine was not one of our nation’s greatest screen actors.