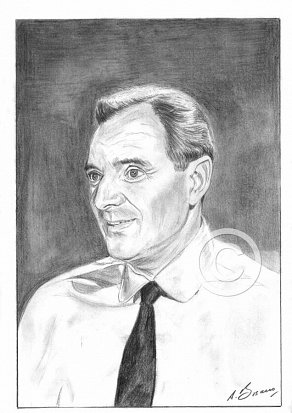

Michael Goodliffe

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Comments

The son of a British vicar, Michael Goodliffe began his acting career at the Stratford Shakespeare Festival. His theatrical activities were put on hold during WWII, when he served five years as a POW.

Picking up where he left off in 1948, he entered films with The Small Back Room, then spent the next three decades playing a vast array of military officers, diplomats, and businessmen. His costume roles included Robert Walpole in Disney’s Rob Roy (1953), Count de Dunois in Quentin Durward (1954), and Charles Gill in The Trial of Oscar Wilde (1960). Though never a star in films, he enjoyed leading man status on British television, notably in the TV series Sam (1973-1975). Michael Goodliffe was 62 when he committed suicide by jumping from a hospital window.

Born 1 October 1914 in Bebington, Cheshire, England, Michael Goodliffe was a regular player in films from the 1950s to the 1970s. Whether as a child at my local cinema or a devotee of the sunday afternoon movie, his face – if not his name – was very familiar to me. He appeared in over fifty during this period, notably Von Ryan’s Express (1965), The Thirty-Nine Steps (1959) and Michael Powell’s highly controversial Peeping Tom (1960). He also featured in To The Devil a Daughter (1976) with Honor Blackman, Sink the Bismark! (1960) with Ian Hendry, and Battle of the River Plate (1956) with Patrick Macnee.

In the Second World War, Goodliffe was captured at Dunkirk by the German Army in 1940 and transferred to a prisoner of war camp. Whilst captive, Goodliffe organised a number of theatrical productions, designed to keep his fellows’ spirits up. He was incarcerated in Germany for five years. Some of his personal recollections of this period in his life can be located at the website link itemised on this page.

In 1958, Goodliffe played Thomas Andrews, the designer of the ill-fated passenger liner the S.S. Titanic, in the classic A Night To Remember. When the account of the Titanic’s sinking was adapted and performed live on Canadian TV a few years earlier, guess who played Andrews? Why, someone called Patrick Macnee!

Goodliffe’s television work included guest roles on many ITC/ATV film series, including Man in a Suitcase, Danger Man, Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) and Jason King (with Peter Wyngarde). He was in one of ITC’s first productions, Heaven and Earth (1956), a filmed, feature-length tale of a deranged preacher running amok on a transatlantic flight. Clearly a precursor of the dreaded disaster genre, then, but it is notable as very probably the first British TV movie, and one of the first anywhere—and it certainly had distinguished theatrical connections, being directed by Peter Brook and starring Paul Scofield (years before their famous collaboration on King Lear), with Leo McKern, Lois Maxwell and Goodliffe supporting. The latter was also in the first episode of H.G. Wells’ Invisible Man, “Secret Experiment” (ATV/ITC, 1959), as a nasty rival scientist who makes off with the unseen hero’s notes for the invisibility formula, and then has to apparently fight with himself in a very silly scene. Apart from the films already mentioned, Goodlife was notable in Michael Powell’s enjoyably sick Peeping Tom (1959), as a character based on John Davis, the notoriously philistine and parsimonious chief executive of the Rank Organisation; judging by the published comments of Powell, Alec Guinness and others, Davis seemed reluctant to back any project that wasn’t a Norman Wisdom vehicle. Accordingly, Goodliffe’s studio boss here had lines like, “If you can see it and hear it, the first take’s OK,” and so no-one missed the point, was named Don Jarvis. Also, in Ken Hughes’ honourable The Trials of Oscar Wilde (1960), Goodliffe was one of the prosecuting counsels, his aggressive questioning leading to Peter Finch as Wilde delivering the famous “love that dare not speak its name” speech.

Goodliffe also appeared as a regular on the gritty and highly successful Thames series Callan, where he played Hunter from “Red Knight, White Knight” (1969), the first episode in its second season, also with John Savident, through to the charmingly titled “Let’s Kill Everybody” (also 1969). His performance in an episode of Man In A Suitcase, “All That Glitters” (1967), was highly impressive and believable as well as timeless, given that there will always be corruptible and hypocritical politicians like the one he played. The episode was, for the record, directed by Herbert Wise, later to helm I, Claudius; Goodliffe played an apparently principled, speechifying politician, seen as a potential party leader and married to wealthy Barbara Shelley (seen in “Dragonsfield” and “From Venus With Love”). He calls in McGill to help locate a kidnapped small boy, explaining confidentially that the boy is actually his lovechild; when McGill asks why he doesn’t simply pay the ransom, Goodliffe’s character replies that he hasn’t any money of his own, that he married Shelley for hers, and she mustn’t know about the son or his political career is finished. As I said, how amazingly unlike real-life politicians, then or now.

One of Goodliffe’s most significant later roles was in Sam (Granada, 1973-75), a period drama series about a young man growing up in the North of England, curiously played by the very Scottish Mark McManus, later a TV icon as the tough cop Taggart; Goodliffe reputedly did much scene-stealing as Sam’s grandad. However, his role in The Man With The Golden Gun (1975) was practically as an extra, and he went unbilled as the Chief of Staff; this is odd for an actor of his stature—perhaps he did have a larger role originally, and it ended up being cut.

Michael Goodliffe became a victim of severe depression and this lead to his suicide on 20 March 1976 at a hospital in Wimbledon, South West London.