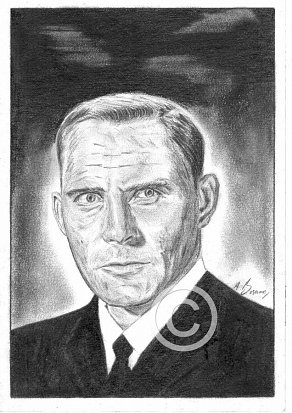

Robert Shaw

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

From Russia with Love (1963)

“You look very fit Nash,” Connery acknowledges rather grudgingly as Robery Shaw sits himself down in his train compartment. This is 1963 and the comment carries no homoerotic undertone, merely a hint of masculine competitiveness, a testing of prestige and male display. Later, when “Nash” orders red wine with his fish at dinner, 007 realises that this ought to have tipped him off.

Connery of course, was no stranger to bodybuilding, having competed in the Mr Universe contest in the 50’s, Shaw on the other hand, was compelled to undertook three months of rigorous gymnasium workouts in order to represent a worthy opponent. His efforts paid dividends, thanks in no small part to Peter Hunt’s editing and the fight choreography which necessitated three day’s rehearsal at Pinewood.

The luck of Ginger Coffey (1964)

Irvin Kershner’s directorial summit, this kitchen sink drama is a notable entry in the genre\‘s film cannon.

Filmed in Montreal, Shaw was fresh from his new found popularity in “From Russia with love,” teaming well with his real life wife Mary Ure, in a downbeat but ultimately hopeful tale of ordinary people with their everyday problems.

Shaw is Ginger, a perennial dreamer in search of a better life. Having moved his wife Vera and daughter Paulie, to Montreal, he continues failing at every job he can find, convinced that each one has impeded his march to the top. “Those jobs weren’t for me,” he tells his wife. “They couldn’t see my true talents”.

Whist Vera and Paulie are losing faith in Ginger, he accepts a lowly position on a paper in return for the promise of a reporter’s role. Ignomy upon ignomy piles up as his wife and daughter leave him, taking up residence with the ‘rich friend’ who found him work with the newspaper. Ginger takes up residence at the local Y.M.C.A. Here he meets a man who works for a local diaper service where he accepts a supplementary delivery job. With his newly acquired dual income, he is able to afford a small flat for himself and Paulie, all the while assuring Vera that his promotion at the paper to a reporter is just around the corner.

Ginger excels at the diaper delivery job, introducing new work innovations, whilst re-designing the company’s logo to draw in more business. Pleased with his work, the diaper service offers him a promotion, a big one, where he can be in charge of taking the service in new directions, yet unthinkingly, he rejects the offer on spec, still convinced that his future lies in journalism.

The paper lays him off and drunk and depressed, he relieves himself on a tree in a public park, being subsequently arrested for indecent exposure. In the courtroom, Ginger encounters preconceived notions about his ethnic background, his palpable humiliation assuaged only by the judge’s leniency. Walking free from the courthouse, Vera offers him encouragement, more firmly convinced of her husband’s true feelings for her, if still unsure what the future holds for the couple.

It’s a touching film, redolent with unfulfilled dreams and aspirations, parental-sibling issues, and day to day practical issues. Shaw is excellent as the Irish dreamer, in a somewhat offbeat choice of role to follow up his new found name awareness, nonetheless establishing his acting credentials throughout. Mary Ure also contributes a solid supporting role, in a rare break from the theatre. A much overlooked movie -I cannot recall any terrestrial screening in Britain – it is nonetheless available to view on Youtube.

Battle of the Bulge (1965)

Spectacular scenes, fictionalised personal stories and an all star cast coalesce to provide the vital ingredients in this motion picture chronicling the Third Reich’s counter-offensive against allied troops marching across Europe. The Germans’ panzar unit is commanded by Col. Martin Hessler, a monomaniacal officer portrayed with chilling efficiency by Shaw, a man hellbent on laying waste the Ardennes region of Belgium, Luxembourg, and France between December 15, 1944, and January 15, 1945. A warmonger by nature, his unit demolishes an amercan held town and its retreating troops inadvertently create a backward “bulge” in the allied line, being spared an ignominious death only by Hessler’s dwindling fuel reserves. His raw recruits, many mere boys, are ready to die for him, and they even break into a rousing song, the “Panzerlied,” that whets his craving for blood.

Henry Fonda is the American colonel who flies reconnaissance in heavy fog to find Hessler. In a race against time he and a handful of Americans (Robert Ryan, Dana Andrews, George Montgomery, Telly Savalas, and Charles Bronson), attempt to burn down the fuel depot crucial to the German supplies.

Despite its historical inaccuracies, the movie is an undeservedly neglected entry in the epic World War II oeuvre. The battle sequences are particularly well staged, the wholesale destruction of buildings and vehicles realistically depicted, and director Ken Annakin deftly handles the logistics of co-ordinating thousands of extras amidst the wintry terrain and Benjamin Frankel’s rousing musical score.

Shaw was interviewed about the film in 1965 and his recollections of the arduous shoot can be located at:

\http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-T-xUqPQV-8\

A Man for all Seasons (1966)

Sir Thomas More was a lawyer and scholar at the court of King Henry VIII. As a devout Catholic, he had serious reservations about the king’s divorce from Catherine of Aragon and remarriage to Anne Boleyn. Refusing to comply with the King’s wishes, he was found guilty of high treason and executed in 1535. In 1935, he was canonised as St Thomas More.

Paul Schofield is the deep thinking More whilst Shaw is a perfect counterpoint as the ebbulient and rumbustious King, arriving on screen in one of the grandest entrances imaginable, a scene I remember well from my trip to the local cinema as a very young man. Surrounded by sycophantic courtiers, whose job it seems to be to guffaw at everything he says, Henry entertains More’s daughter, Margaret Roper, by talking to her in Latin and showing her his shapely legs. The real Henry was proud of his legs, once bragging about them to the French ambassador, until one of them became ulcerated after a nasty jousting accident and the other was allegedly eaten away by syphilis. Whatever the historical accuracy, this scene is set in around 1530, whilst the accident did not occur until 1536. Many historians dispute that Henry ever had syphilis although the film claims that he did.

Shaw remains effervescent throughout, in direct contrast to Schofield’s abundant piety – a classic film.

Custer of the West (1968)

Riddled with factual inaccuracies, particularly the portrayal of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, Shaw’s contribution to the western genre is further bedevilled by one of the last mainstream applications of cinerama, an interesting but fundamentally flawed widescreen format.

The system simultaneously projected images from three synchronized 35 mm projectors onto a huge, deeply curved screen, but unfortunately the picture would only appear natural from within a rather limited “sweet spot.” Viewed from outside this area, the image would become annoyingly distorted. In ‘Custer of the West’, there are no less three prolonged, point-of-view set pieces in the script – a driverless stagecoach’s mountainside descent, a runaway railroad car’s trek towards a doomed trestle, and Custer’s attempt to escape a Cheyenne ambush via a log flum – that had their potential thrill-ride impact diminished as a result.

The film’s chief virtue is Shaw\‘s intense portrayal. Sidestepping Erroll Flynn’s cornball ‘They Died with Their Boots On’ (1941), and Richard Mulligan’s darkly comic megalomaniac in Arthur Penn’s ‘Little Big Man’ (1970), his textured effort highlights the more complex elements of Custer as both a soldier and a man.

The Battle of Britain (1968)

Director Guy Hamilton, fresh from his worldwide success with ‘Goldfinger’ and the second Harry Palmer entry ‘Funeral in Berlin,’ helmed this episodic, all-star World War II film. With Sir Laurence Olivier heading an ensemble cast as flight commander Sir Hugh Dowdling, The Battle of Britain pays tribute to other nationalities instrumental in fending off the waves of Luftwaffe planes, notably the expatriate Polish and Czech pilots. Trevor Howard, Michael Caine, and Michael Redgrave also populate the cast.

Robert Shaw’s characterisation is based on Adolf ‘Sailor’ Malan -74 Squadron Ace, and he’s a commanding presence throughout his intermittent scenes.

The ‘dog fights’ were carefully choreographed, with some of the planes being flown by veteran participants from the real battle. German Ace Adolf Galland, with 104 kills to his credit (35 of them during the real Battle of Britain) was German military advisor. The movie boasts a slew of air-combat sequences, genuine vintage aircraft, realistic-looking miniatures and even some stock footage.

The British were very reluctant to use Polish and Czech squadrons; despite many of these pilots being much more experienced than the British. One of the highest scoring aces in the Royal Air Force during the Battle of Britain was Czech pilot Sgt J František, who flew a Hawker Hurricane with the 303 Polish squadron, and recorded 17 confirmed kills & 1 probable. The ongoing British reticence to deploy them, principally due to the language problem, nevertheless persisted, and this policy is reflected in the film’s narrative.

Most of the fighter plane mockups look decidedly wooden when bombed from above and certain cast members echo this sentiment with their performances. It’s a visual spectacular though, ripe for exhumation and rescreening at regular intervals, yet genuine sub plot development is nigh impossible in view of the time constraint.

\http://www.daveswarbirds.com/bob/behind.htm\

A re-make from GK films is in the works, with a screenplay from Robert Towne (‘Chinatown’), in which we are promised an array of human interest stories and the mandatory CGI input. Before that, we may be overwhelmed with American revisionism in Michael Mann’s ‘The Few’, starring Tom Cruise as Billy Fiske, an american who flew with the Eagle Squadron, a group of volunteers that came to England to fight the Nazis and join the RAF.

He signed up to fly in the battle, yet failed to record a single ‘kill’ before his own early death. ‘I’ve heard it is almost like he won the war all on his own,’ said war veteran Ben Clinch, who loaded the guns fired by the real Billy Fiske. “I can’t see how they can make a film of Fiske’s life. He was unremarkable, in the context of the squadron. He was just another pilot as far as we were concerned.” A minor problem for Hollywood and clearly surmountable.

The Hireling (1971)

The Sting (1973)

The Taking of Pelham 123 (1974)

Forget the two remakes – this is the definitive original version of Morton Freegood’s novel, featuring Walter Matthau at his laconic best as the New York City Transit Authority police lieutenant, and Shaw as the head of a four man hijack team that takes control of a subway train with eighteen hostages.

New York City features heavily, filmed on location with gritty, decayed ’70s realism, ably complemented by a cosmopolitan cast of characters, part ethnic and loud, but also fearless and funky, from the ditsy Koch-like Mayor to the terrified but plucky passengers.

Shaw is steely military precision, ultimately undermined by a psychotic Hector Elizondo, whilst dependable support player, Martin Balsam, handles transportation issues and a mid-winter cold.

Gesundheit indeed!

Jaws (1975)

Shaw wasn’t even first choice for the role of Quint, the shark killer but after Sterling Hayden pulled out, he was approached by Universal to take on what would be his defining role.

The film’s troubled shoot is well documented and was equally beset by Shaw’s moods and alcohol abuse. Roy Scheider (Chief Brody) said Shaw was “a perfect gentleman whenever he was sober. All he needed was one drink and then he turned into a competitive son of a bitch.” He also enjoyed a long-running feud with co-star Richard Dreyfuss. Shaw would be drinking between takes and challenge the much younger man to crazy stunts. Dreyfuss said: “He acted like he had my number. And he did. He made me doubt things I already knew.”

Nevertheless, he lit up the film, ad-libbing songs and one-liners and as the weeks progressed, saw sufficient commercial potential in the storyline to approach Universal with the outlandish proposal to swap his $500,000 salary for a small percentage of the profits. In view of the production delays and concern over the project’s completion, the studio might well have ceded to such a request. As it was, Shaw had to content himself with the salary and the kudos associated with the biggest film of his career.

I read the book – Benchley’s opening chapter was spine tingling – saw the movie, and swam uneasily in the sea for the next three summers!

Black Sunday (1977)

The Deep (1977)

Force Ten from Navarone (1978)

Recommended reading

Robert Shaw: More Than a Life (Karen Carmean) 1994

Shaw wanted to be remembered more as a writer than an actor and Carmean acknowledges that fact with in depth discussions about his literary works. The book also vividly portrays the many, often conflicting facets of this complex man, via interviews with Shaw’s family, friends and colleagues yet remains long out of print and virtually impossible to find at an affordable price.

John French. Robert Shaw: The Price of Success (John French) 1993

Long out of print. and extremely difficult to find, this is an excellent incisive biography now available via Amazon Kindle at a very affordable price.

French was Shaw’s agent for the last five years of his life, and was responsible for finding challenging work that excited his client. Unfortunately, the projects he set up – a BBC version of ‘King Lear,’ an Arthur Hopcraft scripted film based on the Philby, Burgess and Maclean story – were pushed aside by megabuck movies organised by his American counterpart John Gaines. French soon found himself organising more mundane domestic affairs – the schooling of Shaw’s ten children and the chivvying of recalcitrant building contractors on the actor’s Irish estate -an d the book is full of the intimacies of financial and domestic affairs. The author undoubtedly saw his subject in close up and – despite being fired a few months before Shaw died – liked him. Shaw could be so overtly disagreeable that his legacy requires a sympathetic biographer.

Unfortunately, the actor was unfashionably macho, insanely competitive, embarrassingly drunken, and therefore does not easily command sympathy. French recounts a dinner-party conversation where Shaw, who liked to shock his guests, complained that Mary Ure, his second wife, refused to let him bugger her. ‘My first wife used to love it. But Mary says it hurts too much.’ ‘Robert,’ Mary replied firmly, ‘you’re such an arsehole, why don’t you bugger yourself?’ Personally speaking, I’m uncomfortable with the perennial need in certain individuals to shock others. It isn’t simply a question of becoming excessively boorish, but good taste dictates that certain subjects are NEVER discussed outside the sanctity of a relationship, irrespective of whether the union endures or has ended acrimoniously.

The Man in the Glass Booth (1967) Robert Shaw

Shaw had a second career running parallel with his acting, as a respected and award-winning novelist and playwright. His first novel ‘The Hiding Place’, was later adapted for the film, ‘Situation Hopeless… But Not Serious’ (1965) starring Alec Guinness. His next, ‘The Sun Doctor’ won the Hawthornden Prize while for the theatre he wrote a trilogy of plays, the centerpiece of which was his most controversial and successful drama, The Man in the Glass Booth (1967).

‘The Man in the Glass Booth’ dealt with the issues of identity, guilt and responsibility that owed much to the warped perceptions caused by Shaw’s alcoholism. Undoubtedly personal, the play however is in no way autobiographical, and was inspired by actual events surrounding the kidnapping and trial of Adolf Eichmann.

http://www.historytoday.com/richard-cavendish/adolf-eichmann-kidnapped-argentina\

In Shaw’s version, a man believed to be a rich Jewish industrialist and Holocaust survivor, Arthur Goldman, is exposed as a Nazi war criminal. Goldman is kidnapped from his Manhattan home to stand trial in Israel. Kept in a glass booth to prevent his assassination, Goldman taunts his persecutors and their beliefs, questioning his own and their collective guilt, before symbolically accepting full responsibility for the Holocaust. At this point it is revealed that Goldman has falsified his dental records and is not a Nazi war criminal, but rather in fact, a Holocaust survivor.

The original theatrical production was directed by Harold Pinter and starred Donald Pleasance in an award-winning performance that launched his Hollywood career. The play was later made into an Oscar nominated film directed by Arthur Hiller and starring Maximilian Schell. Unfortunately, Shaw was unhappy with the production and asked for his name to be removed from the credits.

The forgotten novels of Robert Shaw

http://www.withnailbooks.com/2014/01/the-forgotten-novels-of-robert-shaw.html

Comments

Last Update : 09/06/16

It’s the merest of ice cold sneers, a near contemptuous air of superiority as the assassin looks down briefly at his silencer and then back at his impending victim.

“The first one won’t kill you; not the second, not even the third… not till you crawl over here and you KISS MY FOOT!”

The dialogue is chillingly delivered by the steely blued eyed actor and the agent on his knees (played by Sean Connery), looks desperate, his options disappearing by the second. This scene from the second 007 epic, a moment anticipated by cinemagoers throughout the preceding ninety minutes, turned the enigmatic Robert Shaw into a genuine bona fide star.

Shaw, who died in 1978, three years after he won international acclaim for his starring role in “Jaws,” the movie credited as the first blockbuster, grew up on Orkney and is well remembered in his former home town. At the time of his death, he had expressed no desire to vegetate in his declining years, preferring instead to exploit his box office popularity for a few more years and then to retire to his Irish sanctuary. Tending the land, writing and playing out his role as the honoured patriarch amongst his loving and possibly still expanding family featured heavily in his plans.

The hardman star, also famous for giving Sean Connery his toughest fist-fight as evil agent Red Grant in the Bond movie ‘From Russia With Love,’ spent most of his career playing villains or anti-heroes in Hollywood hits such as ‘The Sting,’ and ‘Battle of the Bulge.’ The accomplished stage actor was also a successful writer, with several published works to his credit, and wrote the standout USS Indianapolis monologue scene in ‘Jaws’ that explained his character’s frenzied hatred of sharks. Yet off screen, he was renowned for his fast living and hard drinking, earning a reputation as one of the noisiest hellraisers in the business. He was also one of the most prolific actors around, a work ethic which some might attribute to his three marriages and ten children. Nevertheless, whatever his motivation, there was never any doubting his acting talent and enormous screen charisma, even if many of his appearances were representative of an uneven career.

At fifty, he claimed to be mellowing after long years of struggle for commercial success. Talking to a reporter, he was quoted as saying that – “It’s been a strange movie career, not a slow steady progression, but good years followed by bad in a disheartening sequence. I’m enjoying my seventh resurgence now,” he mused, an edge of sarcasm creeping into his deep voice. “It was luck that they kept on discovering me.”

Though long acknowledged as a fine actor, Shaw had rarely won the starring role in films. “I was never really a character actor — I was a leading man who was always cast as a character,” he explained. “I wanted to be Jack Nicholson or Jean Gabin.” The closest Shaw had come to winning an Oscar was a 1967 nomination for his supporting role as Henry VIII in ‘A Man for All Seasons.’ The award that year went to Walter Matthau for “The Fortune Cookie,” the first of many pairings with Jack Lemmon.

Shaw was living in Ireland at the time of his death, for both the country life and its less punitive tax regime. Elucidating further, the actor went on to add that : “I still don’t think of myself as a star. Success lasts only three seconds. After that you’re the same as you were before you had it. I’m not a true artist anyway because I refuse to shrug off my family. To support them I must work in commercial films. My taxes alone keep eight lawyers busy, and when I finally get my money, it’s only one-third of what I earn. With the kids in school and my other responsibilities, I get no change back from the first million dollars. The money flows out like water.” He did concede that his family would survive if he never appeared in another movie yet still wanted the best for his kids. That didn’t mean he was mercenary but “having been brought up in a capitalist competitive world, I retain its traditions. There’s no future in being poor.”

Robert Shaw was born in Lancashire and raised in Cornwall, where his father, a doctor, committed suicide. Shaw, too, was a manic depressive and competitive to the point of lunacy, literally with any activity, running, gambling, table tennis, anything. Fresh from filming “Jaws,” Shaw travelled to Spain for location work on “Robin and Marian” with Sean Connery and Audrey Hepburn. The English writer and comic actor, Ronnie Barker, had a small part as one of Robin’s merry men and his recollections of Shaw appear in Bob McCabe’s authorised biography of the comedian (BBC Books 2004). He found Shaw, cast as the Sheriff of Nottingham, a mercurial character. “I remember we were having a half day and it was lunchtime. Everyone had had a few I think, and Robert Shaw was saying how he loved playing boules.”

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Boules\

“Now I’ve played it a bit. He was always challenging people to things to show them he was the best. He said “I’ll bet you a hundred pounds, I’ll give you eight points and I’ll beat you to thirteen points. I said OK. And everyone came out to watch us, the other actors. It was like a tournament. He started to catch me up. We got to the point where he had a ball right next to the jack and – they were all rooting for me – I had one ball left and I thought “I’ve got to bomb him out of here. I have to do this”. I took aim and it flew right out and a great cheer went up. He was very angry, very upset about it. _“Bastard” he said and threw his money down. I felt so elated. It was like David and Goliath. He was a nice man but he was aggressive.”_ Barker’s approach to the game was the correct one but where interraction with characters like Shaw is more regular, perhaps amongst (say) family members, work colleagues or friends, I’ve tended by default, to let them have their day, whatever my ability to compete. Their competitive instinct makes for boorish behaviour when results do not go in their favour and frankly I’m not concerned enough either way. In any event, it’s impossible to truly change one’s personality – even some form of moderation is extremely difficult and Shaw was clearly disinterested in changing his outward demeanour. Reflecting on an encounter with the mercurial star, actor Christopher Plummer recalls in his autobiography “In spite of myself”:

‘One evening, soon after _‘The Battle of B(ritain’) had wrapped, enjoying yet another delectable supper there (L’Etoile on Charlotte Street, London), I was just coming out of the boys’ room when I felt a stabbing pain in my right foot. Robert Shaw had stamped firmly on my shoe, pinioning me to the floor. “We’re doing ‘The Royal Hunt’ in Spain one month from now as a film”, he announced between his teeth. “You’re going to play Atahuallpa and I’m going to play your old part Pizarro! Say yes now and I’ll take my foot off ya!” – I had no choice but to say yes. “Right!” the Cornish rooster crowed. “You’re free to go.”

Shaw’s second wife was the stage actress Mary Ure, perhaps unjustly best known nowadays for her supporting role in the World War II blockbuster “Where Eagles Dare.” She became involved with the actor whilst still married to the playwright John Osbourne. There are parallels in Ure’s life with her husbands; an inability to stand her ground, to persue her professional goals and the spiralling descent into recreational drinking and then alcoholism.

The marriage between Mary and John would only last five years; his extremely complicated love life, womanising, abusive behaviour and their differences of opinion on starting a family contributing greatly to the breakdown. It was also noted at this time that Osborne was beginning to resent Mary’s growing dependence on alcohol.

Osbornе’s cruelty was observed by the writer Doris Lessing, who watched as Mary was reduced to tears in a bistro by one of John’s verbal attacks: ‘I was there with somebody else and we attempted to defuse the situation, but he never let up for a second. He flayed her, quite like Jimmy Porter.’

The impending breakdown in her marriage in the late 50’s led Mary into an affair with Shaw, then a fast rising star as a result of his starring role in the ITC series “The Bucaneers.” Discretion was not a word in the actress’s vocabulary for whilst Osbourne was at least making some attempt to keep his affairs hidden, Mary was positively indiscreet with hers, going out of her way to leave correspondence from Shaw lying round the marital home for Osborne to discover.

I first became aware of Mary Ure for her performance in the 1959 film ‘Look back in Anger,’ starring Richard Burton and Claire Bloom. It was later suggested by Burton in his autobiography, that he and Mary had had a brief affair during filming which is pure inconsequential trivia but more than likely in view of Burton’s predatory habits.

In 1960, Mary Ure starred as Clara Dawes in the screen adaptation of DH Lawrence’s ‘Sons and Lovers’ and was nominated for both a Golden Globe Award and Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress. Unfortunately, despite her rapidly rising star, her personal life was still an extraordinarily tangled web, as evidenced by the fact that whilst Osbourne was on holiday in the South of France with his mistress Jocelyn Rickard in 1961, Mary was giving birth to a son. In his book “Don’t let the bastards grind you down” (Arrow Books 2011), Robert Sellers confirms that, by this stage, Shaw’s life had descended into utter farce. Having made Mary pregnant, he discovered a few weeks later that his wife Jennifer was also expecting. Not only was he shuffling between a home life and his mistress, but now he had to juggle two impending fatherhoods. Urged by friends to stay with Jennifer, a woman who had been content to forgo a promising acting career to be a wife and mother to Shaw’s children, the actor ignored their advice, laying the foundation for one of the most famous celebrity marriages of the 60’s.

Mary’s son Colin Murray Osborne, named after her Scottish Father, was born on the 31st August 1961. Even though Osborne was named as the Father on the birth certificate, it was widely believed that the child was Shaw’s, and tellingly, the actor formally adopted the young child two years later. Shaw was delighted at having a son. All his children with Jennifer were girls and, though he loved them deeply, like Henry VIII, it was a son he truly longed for. During the time both women were pregnant, Shaw was reportedly telling friends how he was going to solve the problem, choosing between wife and mistress. ‘I’ll go to the one who gives me the boy’. Perhaps many interpreted his remarks as pure flippancy but, with my experience of people and life, he was deadly serious. In any event, with his estranged wife giving birth to another daughter, the dilemma was soon resolved. Heaven only knows what the actor would have done though, had the results been different. As it was, he was holed up in New York so cutting ties with his wife and children in England was conveniently left in the hands of solicitors.

The Osbornes finally divorced in 1962 and she wedded Shaw on April 13th 1963 in secret in Buckinghamshire. Their honeymoon was spent in Istanbul where Robert was playing the vicious assassin Red Grant in the 1963 Bond film ‘From Russia with Love.’

At the time, and away from a pretty volatile, and at times violent, home life, Mary’s professional career had also started to settle down. Mary continued to star in a few plays in London during the 1960’s, including Arthur Miller’s ‘The Crucible’ and ‘Duel of Angels’ with Vivien Leigh.

Mary and Shaw would have four children together (eight in total including four from Robert’s previous marriage to Jennifer Bourke) and everything appeared well, with Mary quoted as saying, “they enjoyed a gloriously loving, combative, thoroughly agreeable relationship.”

As a young boy, and without any conscious forethought I saw them both on the big screen throughout the 60’s. For my ninth birthday my parents took me to see “Custer of the West” in which Shaw and Ure recreated their real life position as husband and wife on the big screen. I had seen Shaw earlier in “From Russia with love” and as Henry VIII in “A Man for all Seasons.” More recently, I acquainted myself with her role in the 1962 Sci-Fi drama ‘The Mind Benders’ in which she starred with Dirk Bogarde.

In 1968, Mary played a beautiful and gutsy allied agent in the block buster adaptation of Alastair MacLean’s ‘Where Eagles Dare,’ opposite Clint Eastwood and Richard Burton. TCM has periodically run a small “making of” featurette about the movie, and Elizabeth Taylor appears as a dutiful, ever present wife on the location shoot, either bereft of suitable film projects herself or merely there to ensure her husband’s feelings for Ure were not re-ignited. It was a box office smash but it was also to be Mary’s last big screen role for five years.

Robert Shaw was fiercely protective, and some say jealous, of Mary, and he insisted that she take a step back, and concentrate on being a full time mother and wife. Mary didn’t give up her career entirely, but the demands of motherhood, she bore three children during this period, and her growing dependence on alcohol meant her career lapsed. Shaw’s motives may well have been predictably sexist but perhaps also pragmatic and indicative of his desire for a stable homelife. Looking back on Ure’s life after her appaulingly early death at forty two, Shaw’s agent John French, was moved to say – he had taken all her cash, demolished her job and made her into a housekeeper.’

As her alcohol dependence increased, Mary tried to resurrect her career in 1973 appearing in what was eventually her final film ‘A Reflection of Fear’ with Shaw. Mary appeared dissipated and it was evident that she was unwell.

Nevertheless, the couple would continue working on joint projects, a one off drama “The Break” premiering on the ITV network in January 1974. The following link contains a scan of the original article that accompanied the broadcast.

http://www.britmovie.co.uk/forums/actors-actresses/111819-robert-shaw.html

She attempted a return to Broadway in 1974 in The Phoenix Theatre’s production of Congrieve’s “Love for Love” but she was unceremoniously released after a disastrous Saturday matinee performance, being replaced by her understudy the then unknown Glenn Close.

It is reported that whilst residing in New York, Mary was found naked in Central Park. According to Shaw’s agent John French, Mary’s reaction to liquor was very different to that of her husband’s. It launched her into turbulent rages, and she became very abusive, feeling compelled to rid herself of her clothing. The couple had by now moved to Ireland for tax reasons, but the cracks in their marriage continued, with Shaw having an affair with his secretary and Mary continuing to seek solace in alcohol.

In 1975 Mary took a leading role with Honor Blackman and Brian Blessed in the Don Taylor stage-play production ‘The Exorcism,’ adapted from the 1972 BBC TV film production of the same name – a sinister tale of a group of friends trapped in a cottage at Christmas, it was to be Mary’s last role in life. A few hours after it had opened on the London stage Mary Ure was dead on 3rd April 1975. The circumstances of Mary’s death led the sensational press to talk of a ‘curse’ on the production in which she was appearing.

It was her husband Robert Shaw, returning home from a break in filming, who discovered his wife dead in their Curzon Street home. At the time, there was much speculation that Mary had committed suicide. I recall an interview with the actress Honor Blackman in the weeks following her death, in which she appeared troubled by the manner of her friend’s passing. Later, at the inquest the actual cause of her death was revealed as accidental death; a tragic combination of prescription drugs and alcohol.

Since the birth of her daughter, Hannah, six years earlier, and at the start of her break from the limelight, Mary had been on prescription medication for depression and often became careless with the dosage. On the night of her death, she had indulged in a few drinks at the play’s opening night party and had arrived home to take some her prescription drugs, a combination that proved fatal.

Shaw, by his own admission, went on a bender after her death. It happened only hours after she opened in a new play. “Her stage comeback had been a huge success,” the actor recalled, “I didn’t go partying with her because I had to get up early the next morning for a film. She came home, took two pills and slept on the sofa so as not to disturb me. She never woke up to read her marvelous notices in the papers. Technically, the pills after the champagne killed her. It was a nightmare, though I don’t feel guilty about Mary’s death, and I can’t take the blame for it.” Revealingly he further added that “it was a happy release for her because she was suffering from the early stages of a cancer tumor — unknown to anybody.”

In the summer of ’76, and little more than a year after Mary’s death, Shaw married his longtime secretary, Virginia “Jay” Jansen, and their first baby was born in New York that December. In addition, Shaw’s third wife had an older son whom Shaw had adopted years ago. There had always been some mystery surrounding Jay’s older son, Charles, but the Shaws talked quite openly about the circumstances. “Everyone always thought Robert was the father,” she admitted at the time – the truth is I became pregnant during a mad affair with a French musician. I paid for an abortion in Denmark but I was tricked. Nothing was done, and I decided to have the baby.” Backpedaling at this stage of the interview, Shaw added that “Never once while I was married to Mary did we play around.”

Jay also admitted that, at first, she had resisted the idea of marrying Robert. “I didn’t want to be a film star’s wife; I’d seen enough of what it meant traveling exhausted around the world living from suitcases. But I’m happy he finally wore me down, and I changed my mind. It was only after I agreed to his final proposal that I stopped calling him Mr. Shaw.” Her new husband added ominously that “Virginia was pregnant when we got married, but then all my wives have been. She loves me more than the other two did. She’s a better wife than secretary. And she’s got another thing coming if she believes our new baby will be the only one — having kids keeps you young.”

Unsurprisingly, Shaw was lying about the extent of his involvement with Virginia whilst he was married to Ure. Whether it was the effects of her medication or the crumbling state of her marriage, Shaw’s biographer John French writes in chapter thirteen of his book that: “Though she knew full well that he had no interest in philandering with other woman, she still suspected, she ‘knew’, he was having an affair with Miss Jay, which was a great deal worse since it was carried out, presumably, in her own home.” In the following chapter, French confirms – via a recollection from the Nobel prize-winning playwright – that when Shaw visited his friend Harold Pinter in London in 1975, he told him that he was having an affair with Virginia, and what was more, that she was pregnant.

Sadly, for Shaw, there was precious little time left. He died suddenly of a heart attack at the age of 51 on August 28, 1978.

The events of that day are recalled in the following link:

http://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001727/bio\

I was in Gibraltar at the time with family when I heard the news about Shaw, and thereafter recall watching my father incessantly at the beach for three days as he swam those huge distances he was more than capable of negotiating. He was five months younger than Shaw and appeared indestructible to me. Now I saw him in a different light. It was a stressful time in his life workwise, and he exercised rigorously in order to endure the 45,000 miles he would drive every year. We had been to see “Jaws” a couple of years earlier and he had been shocked by Shaw’s appearance in the film. He was right, for in little over a decade since “From Russia with love,” the drink had definitely taken its toll.

Ultimately, the feeling persists that Shaw was a man who over-complicated his life, placing untold financial pressure upon himself. Utilising ‘remittance basis’ taxation rules, he would be compelled to meander around the world, working no more than ninety days in whichever country he was filming, flying aimlessly to somewhere – anywhere – at weekends, to avoid breaching the appropriate rules. When the UK Inland Revenue came after him, he was faced with either a mountainous tax back payment, or the realisation that he could never set foot in England again. Ultimately, both parties would agree on a full and final settlement payment of £120,000. From a planning perspective, his use of ‘shell’ companies had worked well – his marginal tax rate on earnings since 1965 little more than 15%. But was it all worth it? The stress involved with any tax investigation, his untold financial commitment to such a large family, the never ending cost of restoring his Irish residence, and the relentless guilt he felt over Mary’s death, all exacerbated his drinking problem. Yet Shaw was a compelling actor – given the right material – and an intuitive writer whose work deserves wider recognition.