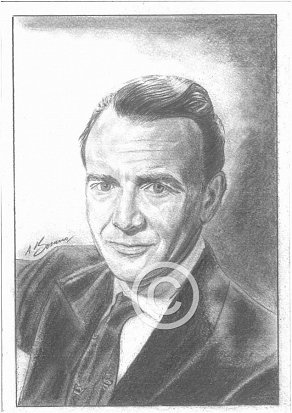

Sir John Mills

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

The October Man (1947)

Director Roy Ward Baker’s Brit noir feature wins no ‘whodunnit’ awards, yet remains a top drawer pschological thriller. Exploring a central issue he would return to in ‘The long memory’ six years later, Mills decamps to lodgings in a London boarding house after a period of covelescance following a tragic accident. Traumatised by the death of his friend’s child in a bus crash whilst treating her to a day out, Jim Ackland (Mills) subsequently suffers from periodic amnesia and suicidal tendancies yet is eventually released back into society.

Returning to gainful employment as an industrial chemist, Jim is doing well yet his surroundings bode ominously for the future. Amongst the hotel’s patrons is a motley collection of narrow minded, spiteful, suspicious, vengeful, and lonely people, all ill equipped to assist in his rehabilitation into society. When he financially assists one of the young female residents who is subsequently murdered in the nearby park, Jim arouses widespread suspicion, despite having no recollection of committing the dastardly act. Placed firmly in the park at the time of the crime, our chief suspect can only rely on the loyalty of Joan Greenwood, who stays loyal to her man despite her own brother’s misgivings.

There’s a malevolent turn from Edward Chapman, who would find subsequent fame as Mr Grimsdale in the long running Norman Wisdom Rank series, but its Mills’ film, his characterisation full of understatement and grace. At his wit’s end, and all but ready to throw himself in front of a passing train, Ward baker intercuts masterfully to maintain tension to the very end.

A rarely shown mini masterpiece, I first saw the film in the mid 80’s, but subsequent screenings have been thin on the ground.

Scott of the Antarctic (1948)

Seamless matching of breathtaking location shots in Grahamland, Switzerland and Norway, with studio filming at Ealing, elevate this film to hitherto unseen visual heights. Much of the credit must go Jack Cardiff, who had the job of stitching those different colour palettes together with his own studio-bound footage. Much of his Antarctic work, cutting from long and medium location to close studio images is utterly convincing, with a level of finesse one would associate with today’s CGI.

The film is not without flaws however, and the screenplay’s thinly drawn characterisations contribute little to our understanding of Scott, the man. Mill’s narrative nonetheless conveys a sense of isolationism and stoicism in equal measure, but our central focus is repeatedly drawn back to the staggering landscapes, images and Technicolor that sit at the heart of the film.

Whilst it remains an overlong and deferential British movie – Roald Amundsen and his team of norwegian explorers were, after all, first to reach the Pole – there’s a level of scope and ambition hitherto unseen in many of the rather quaint Ealing movies released before and after this hagiography of Robert Falcon Scott.

Mr Denning drives north (1952)

Co-starring Phyllis Calvert and Eileen Moore, Mills is the aircraft manufacturer who accidentally kills his daughter’s opportunistic boyfriend, and tries to dispose of the body. The man called Mados, a known blackmailer, has already been married twice before – his second wife ended her own life – leaving Denning convinced that he can be persuaded to cool his ardour for the princely sum of £500. Taunted about his daughter’s lack of moral virtue, Denning responds with a right hand uppercut sending his adversary backwards into the fireplace. Unfortunately, the fall results in a fatal head wound, and instead of calling in the police, the beleagured father dumps the body in a lonely spot on the road to the North, making it look like a hit-and-run accident. Weeks later there is still no report of the body being found, and Denning starts to go to pieces. When he lets his wife into his secret, the two start making enquiries, possibly making things worse.

What follows is an extremely witty adaptation of Alec Coppel’s novel, in which Denning is guilty of nothing more than manslaughter. Given his previously unblemished character and various extenuating circumstances, the worst he could have expected was a short prison term. Compelled to protect his daughter, and in trying to make the killing look like an accident he only succeeds in making it look like cold-blooded premeditated murder. Now facing a hanging, Denning is caught in a trap of his own devising. Worse still, and in the shortest possible time, his daughter’s interest in the ‘missing beau’ has dissipated in favour of her new US attorney boyfriend, thus rendering her father’s intervention sickeningly premature.

Herbert Lom does double duty playing both the victim and his brother, whilst Mills handles the subtleties of Denning’s gradual mental disintegration with aplomb. There’s also Wilfred Hyde White who excels as the local mortuary attendant, reappearing at regular intervals to unwittingly ramp up the suspense factor.

A much underrated British thriller still unavailable on DVD.

The Long memory (1953)

With a pleasing sense of continuity, Mills reprises the role of a neurotic noir hero first seen five years earlier in ‘The October Man’ (1947). If certain elements of the British cinema going public might have recoiled at the sight of the actor at his most down-and-dirty, it was still a welcome relief from his then decade-long potpourri of bright-eyed Cockney lads, and upright military heroes.

It’s one of those downbeat thrillers for rainy, wintry afternoons, and well suited for those more interested in a comfy sofa and warm brew, than a trip to the local museum.

Convicted for a murder he did not commit, Phillip Davidson (Mills) spends 12 long years in prison, vowing to get even with the three witnesses who perjured themselves, thereby securing his conviction. Returning to the scene of the crime, he begins gathering clues as to the whereabouts of the witnesses.

Amidst the bleak austerity of post war Britain, Davidson lives rough in a beached barge on the Kent Marshes, encountering three individuals who work tirelessly to break down his natural brick wall defences. Jackson is the kindly old hermit from whom he rents the barge; Ilse, a traumatised wartime refugee who falls in love with him after he rescues her from being raped by a sailor and allows her to stay overnight on his barge; and Craig, a journalist who is interested in his case, and also suspects him to be innocent.

Ilse suffers emotionally as the man she has fallen in love with commences the long journey back from glowering, vengeful outcast, to an individual of moral fortitude with a love of life, yet along the way there’s the occasional sign that Davidson’s misanthropy merely obscures a still beating heart.

There are plot twists along the way, before the inevitable denouement and Jackson’s timely intervention.

:http://www.reelstreets.com/index.php/component/films/?task=view&id=572&film_ref=long_memory

Yet more location shots can be located via:

:http://www.zen171398.zen.co.uk/The_Long_Memory.html

I was Monty's Double (1958)

An abiding public affection for war stories – and I must include myself here – bears testimony to Britain’s unceasing nostalgia for its ‘finest hour’ and as a tribute to the middle-weight talent of directors like John Guillermin, who helmed this movie.

Rich in narrative, if perhaps somewhat old-fashioned today, the movie recounts the amazing true adventure of the actor, Clifton-James, who was seconded to impersonate General Montgomery. The plan was to confuse the Germans by placing him in various key sites; an ingenious idea, treated here with a blend of wry humour and total conviction.

Guillermin would also direct the excellent “Blue Max” with considerable verve seven years later, but here he is content to follow the general narrative of James’ book, whilst taking a few liberties with history, most obviously a third act kidnap attempt by a German strike force (a scene that give Mills an opportunity to play the steely hero).

“I Was Monty’s Double” afforded James the opportunity to reprise his real life role. Declassified war documents reveal that although he wasn’t first choice for the role, he was nevertheless, the final choice. James actually General’s pay for the five weeks of his engagement, perhaps to make up for the fact that, in accordance with the state secrets act, this would be one role he could not put on his resumé.The real James, a forty-five year-old World War I veteran serving the war effort at a desk, was a heavy drinker (the film portrays him indifferent to alcohol) and a smoker, vices he had to give up to play Montgomery (who was a teetotaler and a non-smoker). He was fifty-eight when he took up the role again for the film and the years betray him, yet it’s a minor issue. In a pivotal early scene where he is sent to observe the real Montgomery, the film producers intercut real footage of the general with shots of James playing both roles. It’s little wonder the Germans were fooled; after all, this is the race of people who simply took head counts each day at Colditz, rather than working with specific prisoner identification.

The film is carried largely by the personable Mills and the chummy little group that forms around the conspiracy. Cecil Parker is blithely sardonic as his acerbic but affectionate commanding officer and their friendship and mutual respect shows through their lively working relationship.

Ryan's Daughter (1970)

Along comes the role of a village mute in David lean’s love story, and Mills defies all odds to win a Best Supporting Actor Oscar. Set in coastal western Ireland, his performance was validation for years of sterling work. As Michael, the village idiot who cannot speak but knows everything, he remains a total outsider amongst the village community but ultimately, the only person who can really understand Rosy.

There’s an unwarranted epic quality to the film – stunning imagery from cinematographer Freddie Young and the most inherently romantic sex scenes ever filmed – yet director David Lean loses sight of simplicity itself amidst his grandiose visions.

My Grandmother was uncomfortable with Mill’s portrayal, but that sense of unease resides in all of us. Overcoming it in the company of less fortunate individuals defines who we are.

Recommended reading

Up In The Clouds, Gentlemen Please (1981) Revised 2001

If you’re looking for a muckraking read, then pass this volume over. Whilst Mills’s autobiography offers intimate views of a then 50 year career, including many anecdotes about such friends and acquaintances as Noel Coward, Laurence Olivier, David Lean, and Lord Mountbatten, his recollections are candid yet hardly confessional.

This autobiography was updated twenty years later and offered interesting insights into the actor’s battles with the ravages of time – failing eyesight and the daily toil with learning scripts – yet underscoring everything is a real love for his family and friends, a sentiment self evident throughout each and every chapter. Surrounded by wife Mary and their two daughters, Juliet and Hayley, life was often idyllic in their dream home in Denham, As the actor so aptly put it – “one of the most beautiful houses I have ever seen… We fell madly in love with the house the moment we walked in through the front door… It was quite perfect, exactly what we wanted, where we wanted.”

It’s nothing if not an uplifting read, carefully annotated by a charming, fascinating, and considerate man; a hoofer to the end.

Comments

A wiry, former song-and-dance man, John Mills would become one of the most significant of all British film stars, and in his nearly 60-year career appeared in well over a hundred films, as well as substantial theatre and TV performances.

One of life’s true gentlemen, the many testimonies of individuals fortunate enough to have met him bare testimony to his humility, and self effacing demeanour.

Blessed with a professionally rewarding and much fulfilled private life, Mills was one of life’s fortunate individuals and had the good sense to recognise it.

In 1958, he filmed “I was Monty’s Double” on location in Gibraltar and there began a lifelong affinity with the rock, a location in which he would holiday each year. The Rock Hotel, where Mills and his wife would always stay, was built by John Crichton-Stuart, 4th Marquess of Bute, and began operation in 1932. In the years after it opened, the hotel was managed by Rudolph Richard and earned a reputation as one of the finest hotels in Europe; other notable guests including Winston Churchill, and Errol Flynn.

Location shots from the making of the film can be located via:

http://www.reelstreets.com/index.php/component/films_online/?task=view&id=2416&start=10

http://www.warhistoryonline.com/featured-article/i-was-montys-double.html

In 2001, Mills renewed his wedding vows at the age of 92 in order to overcome one of his biggest regrets. The veteran actor had been denied the opportunity of a full church service 60 years earlier when he tied the knot with his wife Mary. The couple had married at Marylebone register office while he was on leave from the Army during the Second World War, and it remained a lifelong regret not being able to have a church wedding. A special service at St Mary’s Church, adjacent to his Tudor mansion, Hills House, in Denham, Buckinghamshire, offered considerable consolation to the couple, and later that spring, they would whereupon in Gibraltar. After the ceremony, Sir John told the BBC, with a broad smile: “The first 60 years are the worst, so we’re hoping to push on from here.”