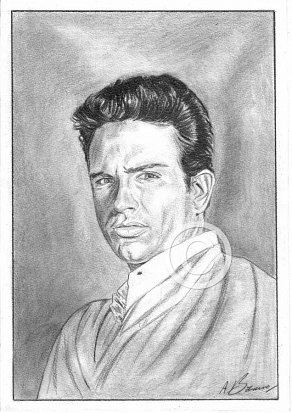

Warren Beatty

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Splendour in the grass (1961)

Bonnie & Clyde (1967)

Another of Beatty’s films that I haven’t seen in more than four decades, yet one that still resonates with me to this day. ‘Bonnie and Clyde’ (1967) is one of the sixties’ most talked-about, volatile, controversial crime/gangster films combining comedy, terror, love, and ferocious violence. It was produced by Warner Bros. – the studio responsible for the gangster films of the 1930s – and it seems appropriate that this innovative, revisionist film should have redefined and romanticised the crime/gangster genre and the depiction of screen violence forever.

in her book “Warren Beatty – A private man,” biographer Suzanne Finstad devotes a near twenty pages to the film’s gestation. Apparently, despite his unerring eye for period detail, the actor would veto an authentic 30’s look – hair slicked down, parted in the middle and shaved at the sides – in the interests of vanity. It’s an amusing aside – Beatty would have looked simply laughable, as indeed many men from the depression era did – and in any event, he had a co-conspirator in Faye Dunaway, who similarly rejected authenticity, and an original ‘marcel wave.’

On set, Beatty, in his dual role of star and producer, was professionalism itself. Co-star Gene Hackman, who would use the film as a launching pad for his own career, remembers Warren as “the soul of tact and kindness.”

Initial reviews were dispiriting – as the following link attests –

http://sensesofcinema.com/2006/feature-articles/bonnie_and_clyde/

Nevertheless, the set pieces are excellent, and the on-screen chemistry between Beatty and Dunaway fairly sizzles with concupiscence, despite his thinly veiled impotence.

Warners showed their distinct lack of faith in the project by offering their star a 40% profit share. A year later, and with the film posting box office receipts sufficiently large enough to place it second in the company’s list of all time biggest grossing movies, Beatty was pissing himself all the way to the bank.

The Parallax view (1974)

I vaguely dozed my way through “Parkland,” Hollywood’s 50th anniversary big screen recreation of the Kennedy assassination. One’s sympathy for a young medical team suddenly thrust into a surreal ‘day from hell,’ was more than exceeded by the sheer incredulity that a film about such a momentous moment in American history would ask no questions and deliver no answers.

Fortunately, Hollywood has previously seen fit to release several thought provoking movies about the subject. ‘JFK,’ Oliver Stone’s epic mega-budget version of events was essentially a retread hagiography of Kennedy theorist Jim Garrison, a bombastic New Orleans prosecutor and homophobe who tried to convict a gay CIA associate, Clay Shaw, of the president’s murder. Garrison’s case was ultimately flawed and unconvincing: the jury finding for the accused innocent, which undercuts Stone’s telling of history. Nevertheless, the film provoked a public outcry and led to the release of thousands of previously secret files by the Assassination Records Review board.

Eighteen years earlier, there was the low key ‘Executive Action,’ that mixed documentary footage with live action, and portrayed the assassination as a conspiracy by the CIA and big business interests. Burt Lancaster played the CIA coup leader, while Robert Ryan and Will Geer played Texas oil men who want Kennedy dead.

For my money, the best JFK conspiracy movie isn’t, strictly speaking, about the Kennedy assassination. Made in 1974, Alan J Pakula’s ‘The Parallax View’ borrows from the murders of both Kennedy brothers, to tell the tale of a mysterious organisation, the Parallax Corporation, which deals in political assassination and the creation of “lone assassin” patsies.

Under construction

Comments

Oscar winner Warren Beatty, wrapped principal photography on his Howard Hughes movie in May 2014, his first starring role since he directed himself in “Town and Country” in 1991.

Vaguely bored with tinseltown, he had devoted the preceding two decades to raising his children and ‘talking politics.’

The $27m romantic drama, which began filming in February 2014, had been a lifelong ambition for Beatty and focused on the latter years of the eccentric billionaire. It followed Martin Scorsese’s 2004 portrayal of Hughes’s early life in ‘The Aviator’ and represented, what many perceived, would be the enigmatic star’s last screen portrayal.

Beatty’s body of work is slim, and the majority of his films are rarely screened on either terrestrial television or on ‘pay per view’ services. Due to the increasing editorial and proprietorial control he has exercised over his work, his movies are unlikely to ever fall into the public domain. Public Domain is an intellectual property designation refering to the body of creative works and knowledge in which no person, government or organisation has any proprietary interest such as a copyright. These works are considered part of the public cultural and intellectual heritage of content that is not owned or controlled by anyone and which may be freely used by all. According to Wikipedia: “These materials are public property, and available for anyone to use freely (the “right to copy”) for any purpose. The public domain can be defined in contrast to several forms of intellectual property; the public domain in contrast to copyrighted works is different from the public domain in contrast to trademarks or patented works.” The laws of various countries define the scope of the public domain differently, making it necessary to specify which jurisdiction’s public domain is being discussed.

He is obviously a perfectionist when it comes to making movies, which is one explanation for his relatively small filmography. As Beatty once said about filmmaking:

“It is all detail, detail, detail. When…the person you are working with has to go home and return a call to his press agent, and lunch is being served, and the head of the union says, ‘Well, you have to stay out there for another 10 minutes because they have to have coffee,’ and then the camera breaks down, and there is noise, a plane flying over, and this wasn’t the location you wanted…are you going to have the energy to devote to the detail of saying, ‘That license plate is the wrong year’? That’s where the stamina, the real fight comes in.”

Beatty is well-known for shooting numerous takes of scenes. Buck Henry, his co-director on 1978’s “Heaven Can Wait,” once said, “Ideally, Warren would never, ever, ever finish anything, because there’s always got to be a better way to do something-the shot, the edit, or the scene, or the line, something.” One of the hardest parts in the act of creating is knowing when the act is finished, when to step back from it and say, “It’s done.” Can something always get better the more time you spend on it, the more takes you shoot? Beatty seems to think so.

Power reading my way through a pair of Beatty biographies, it became apparent to me that he has applied this same obsessive attention to detail to every stage of a film project, from the acquisition rights and early drafts to a completed screenplay. Years would fly by, much of the time spent globetrotting, raising financial backing for scripts that piqued his interest, and dallying, naturally, with women. His reputation as a lothario is legendary but in all honesty, I found reading about his life sheer tedium. The actor Tom Sizemore published a ‘warts and all’ autobiography in 2013, and recalls asking Beatty, when he was first introduced to the notorious ladies man, why he didn’t smoke or drink. Beatty’s reply was succinct and clearly serious. “Because of the way I look.”

It’s not that he hasn’t made films that have matched his cinematic aspirations and political leanings – ‘Bonnie and Clyde,’ ‘Reds’ and ‘Bulworth’ spring readily to mind – yet the feeling persists that here is a man who, but for himself, could have professionally achieved so much more. In the fast changing lane that is Hollywood, word got out that he was impossible to work with. He couldn’t act without directing, and he couldn’t direct without directing life itself: with charm, certainly, but also with his unremitting control freakery and often volcanic temper. Part of the problem with the deservedly forgotten ‘Town & Country’ (2001), for instance, was that according to biographer Peter Biskind’s sources, Beatty “worried every speech to death,” re-analysing and re-editing every breath, pause, verb and comma to the point that no sense lingered. One can imagine someone like Laurence Olivier simplying wringing his hands in despair, and exhorting Beatty to “simply act, dear boy!” I enjoy getting “under the bonnet,” but some people can carry the exercise to unacceptable limits.

More than anything, I simply hope – for the man’s sake – that the legion of stories about his self absorption remain untrue. An assistant director on the 1961 movie ‘Splendor In The Grass’ recalls Beatty sitting in front of a mirror separating his eyelashes with a pin. Years later Hal Lieberman, former president of Universal Pictures, said: “I liked Warren but he was the sun, and everything around him was a satellite. Everything, everything, was all about Warren Beatty. He did have kindness in him, but he had a side of him where you didn’t really exist in his world. He meant everything to himself.” Beatty deflected these comments by adopting the mantra: “You’ll never meet an actor who’s as narcissistic as I am.”