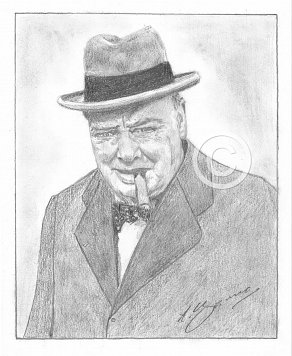

Winston Churchill

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended reading

Churchill (Roy Jenkins) 2001

One of my favourite books on Churchill. Jenkins didn’t believe that intimate knowledge of a person necessarily enhances any biography and to prove his point this magisterial biography is peppered with useful insights that contrast his central political and historical concerns with the limitations of his solipsistic world-view. Whilst there is no general rule that politicians write about other politicians better than anyone else, Jenkins makes a case for this assertion and does much in an engaging literary style to capture the pure essence of Churchill.

Surfing

http://www.winstonchurchill.org/

Registered subscribers receive a quarterly edition of “Finest Hour” the journal of Winston Churchill. Each 64-page issue is packed with fresh insights, reviews and information on Churchill’s life and times by the best Churchill writers and historians—a massive reading experience for students, scholars, teachers and Churchillians.

Comments

As the July 1945 election results started to come in, it was obvious that the magnitude of the defeat reflected a seismic change in public attitude to the demands of post war Britain. The Conservatives were reduced to 210 seats, and the man who had stood, only weeks before, alongside the Royal family on the balcony of Buckingham Palace basking in the heady atmosphere of VE day, was now being unceremoniously ejected from 10 Downing street.

Five years earlier his appointment as Prime Minister had symbolised the phrase “Cometh the hour, cometh the man.” Now, whilst noting the all pervading stygian gloom at No 10 the following day, Churchill’s youngest daughter Mary observed her father’s despondency. The scale of the defeat would deny him the opportunity of meeting Parliament as Prime Minister and so there would only be time enough that day to encounter the king’s incredulity at the election result during his resignation audience with the monarch and to compose his dignified farewell statement. There was a tremendous debt of gratitude owed to him by the British public but practicalities of the day necessitated his departure; unfortunately for Churchill, this wiliest of political campaigners never really believed the destiny of post war Britain would be entrusted to anyone but himself.

The essayist Christopher Hitchens once wrote that Churchill “was not a figure in history so much as a figure of history” yet it cannot be denied that he stands alongside Shakespeare, Newton and Queen Victoria as a towering presence in the British story. I am acutely aware that amongst more than one generation of persons, I, and indeed others, could be labelled a political heretic for even suggesting that Churchill’s reputation is undeserving so I’m not going to do that. In this world there are individuals born to lead, possessed of great oratory and a required sense of detachment to make sacrifices for the greater good of mankind. What interests me are the elemental aspects of a personality capable of overcoming the most introspective of soul searching questions. For most of us, we look back on certain actions in our lifetime and harbour the deepest of regrets; in my case had I not resolutely minimised such behaviour I would have completely lost touch with the person I was in my youth. Nevertheless, I remain troubled to this day by one action on my part yet it did not involve the loss of life. In contrast, at the age of forty, as First Lord of the Admiralty, Churchill was a prime mover behind the Gallipoli campaign, a disastrous attempt to land troops on the shores of the Dardanelles strait prior to capturing Istanbul and forcing route through the Black Sea to Russia. In nine months of fighting the Allies sustained 140,000 casualties and the ensuing defeat damaged his political career. One can only speculate on the additional damage to his inner well being yet his resolve to continue seemingly remained unwavering.

Churchill’s credentials as an orator and statesman were shaped by Bourke Cockran, a charismatic irish-born Democratic Congressman from New York City. After the death of her husband Lord Randolph, in 1895, Jennie Churchill became romantically involved with Cockran and urged him to take her son under his wing.

Congressman Cockran was noted for his ability to move colleagues and constituents to support causes or even change positions as a result of his magnificent oratory. His speeches were noted for their rhythmic quality and presence. Using his body, gestures and his voice to both captivate and move his audience, Cockran displayed an ability to deliver his conversational speeches powerfully, ably assisted by rigorous research and his subsequent mastery of the subject upon which he spoke.

Congressman Charles O’Brien (D-NJ), at Cockran’s Memorial Service was moved to say:

“Much has been said and written about his ability as an orator. For ages to come his will be the standard upon which men of similar genius will be judged. In all history of the world, no man has surpassed and few have equaled him.”

Churchill visited the United States for the first time in November 1895. He was almost twenty-one and was en route to his first military adventure in Cuba. He stayed in New York, where he was lavishly entertained by the politician Bourke Cockran in his Fifth avenue apartment.

Later in life, Churchill would describe the New York Congressman as “a remarkable man. . .with an enormous head, gleaming eyes and flexible countenance.” But most of all, he admired Cockran for the way he talked. The Congressman had a thundering voice and often spoke in heroic and rolling phrases. When Churchill asked his advice on how he could learn to spellbind an audience of thousands, Cockran told him to speak as if he were an organ, use strong words and enunciate clearly in wave-like rhythm. They corresponded for many years. Adlai Stevenson, the democratic nominee for the US Presidency in 1956 and later a leading member of JFK’s cabinet, often reminisced about his last meeting with Churchill. “I asked him on whom or what he had based his oratorical style. Churchill replied, ‘It was an American statesman who inspired me and taught me how to use every note of the human voice like an organ.’ Winston then to my amazement started to quote long excerpts from Bourke Cockran’s speeches of 60 years before. ‘He was my model,’ Churchill said. ‘I learned from him how to hold thousands in thrall.’”

Churchill was in Cuba in 1895 as a military observer of the Spanish-Cuban-American war. There are those who infer that the information on tactics and methods used by the Spanish was put to work in subsequent Boer War, and led to the eventual victory of the British forces in that South African War. On a more personal level, the young Winston’s visit to the front was typical of ambitious military officers of the day, as they sought promotion through the ranks as a direct result of their field reports. What he could not forsee at the time were the ramifications of his time in Cuba more than forty years later when he sought to bring America into the war against Germany.

He was not present of course, when the the Second Cuban Insurrection began on February 24, 1895 but he did observe the severe bloodshed and violence of the war as the spanish wrestled with the forces led by the Cuban resistance leaders Antonio Maceo and Maximo Gomez. Reluctantly, America was drawn into the conflict with at least an interest in monitoring the state of affairs. President William McKinley had been leaning towards war for some time now, and eleven days after Spain rejected the demands of the United States for Cuban independence, he asked Congress for war. Although war had not been declared yet, between April 11th and April 22nd, conflict began, with the U.S. Army mobilizing, Congress declaring Cuba as an independent country, and a naval blockade of Cuba put into place (the first Spanish ship was taken shortly after). Spain declared war on the 23rd, and Congress declared that a state of war had existed since the 22nd. The Spanish-American War had begun. Immediately, the American naval presence began to bombard key locations in Matanzas, Cuba. On May 1st, under the leadership of the rather famous Commodore Dewey, the U.S. Navy’s Asiatic Squadron defeated the Spanish Pacific Squadron at the famous Battle of Manila Bay. Indirectly, through this great victory, America quickly became a real world power (in the eyes of other countries), showing it’s vast naval superiority.

America soon began to make land combat movements. They took Guam (with no resistance) and landed General Lawton’s 5th Corps. Theodore Roosevelt also landed his “Rough Riders” – the 1st United States Volunteer Infantry. The ground battles of San Juan Hill and El Caney quickly determined ground superiority, and the naval Battle of Santiago destroyed the remainder of the local Spanish fleet. The ground troops in Santiago were forced to surrender, and Puerto Rico was taken. Spain, beginning to worry about the possibility of an attack on their homeland, asked for peace terms through France on July 26th.

On August 9th, the Spanish accepted McKinley’s terms of peace, and peace protocols were signed three days later. Peace and order were gradually restored to Cuba. The United States acquired Puerto Rico and the Philippines from Spain, and the war was officially over when the two countries signed a treaty on December 10th in Paris, bringing an end to real conflict in Cuba for some time.

Churchill formed clear and decided views about what he had seen in Cuba. But these did not help him to come down on one side or the other. He had a natural sympathy for people trying to shake off an oppressor, a natural distaste for the high-handed and often stupid actions of the colonial administrators. He saw, moreover, that “the demand for independence is national and unanimous.” In his very first despatch he had written: ‘The insurgents gain adherence continually. There is no doubt that they possess the sympathy of the entire population.’

On the other hand he was frankly contemptuous of the ill-organized, ineffective, destructive and often cruel manner in which the Cuban rebels conducted their campaign. ‘They neither fight bravely nor do they use their weapons effectively.’

Winston later wrote in the Saturday Review on 7 March 1896. ‘They cannot win a single battle or hold a single town. Their army, consisting to a large extent of coloured men, is an undisciplined rabble.’ What he saw of the rebel forces and of the havoc wreaked by them on the economy and administration of the country did not inspire in him any confidence that the insurgents would provide a better alternative for Cuba than the Spanish colonial power. ‘The rebel victory offers little good either to the world in general or to Cuba in particular,’ he wrote on 15 February 1896 in the Saturday Review. ‘Though the Spanish administration is bad a Cuban Government would be worse, equally corrupt, more capricious, and far less stable. Under such a Government revolutions would be periodic, property insecure, equity unknown.’

Sending his friend Bourke Cockran a copy of this article Churchill wrote:

‘I hope the United States will not force Spain to give up Cuba— unless you are prepared to accept responsibility for the results of such action. If the States care to take Cuba—though this would be very hard on Spain—it would be the best and most expedient course for both the island and the world in general. But I hold it a monstrous thing if you are going to merely procure the establishment of another South American Republic—which however degraded and irresponsible is to be backed in its action by the American people—without their maintaining any sort of control over its behaviour.

I do hope that you will not be in agreement with those wild, and I must say, most irresponsible people who talk of Spain as “beyond the pale” etc etc. Do write and tell me what you do think. . . ‘

One can accept that Churchill found it difficult to be overly critical of the very people who were responsible for his food, shelter and safety. Moreover he had been under fire with the Spaniards on his twenty-first birthday, roughing it and encountering some danger with his hosts, a shared experience that made completely objective reporting impossible. Nevertheless, there would be repercussions for Churchill of his time in Cuba before hostilities broke out between America and Spain in 1898. ‘America can give the Cubans peace’ he told the Morning Post in an interview on 15 July 1898, ‘and perhaps prosperity will then return. American annexation is what we must all urge, but possibly we shall not have to urge very long.’

By the end of the 1930’s, the myth had grown that Churchill had been in Cuba during the Spanish-American war, and that he had taken the side of the Spaniards against the Americans. Churchill took every possible step to dispel the myth but it kept recurring, notably at the outbreak of war in 1939 when an American Congressman implied that Churchill had actually been an enemy of the United States in the Spanish-American war.” His time as a young military observer was now threatening to undermine his efforts to bring the single largest industrialised nation into the war. He would court his mother’s homeland throughout 1940 and 1941 with only limited success.