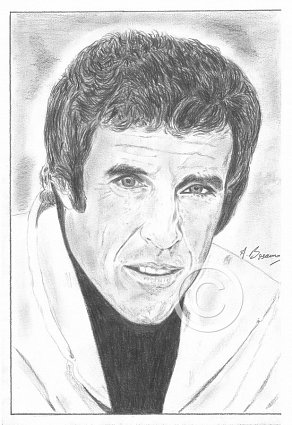

Burt Bacharach

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

Burt Bacharach: Anyone Who Had A Heart – The Art Of The Songwriter (6CD Box Set) Deluxe Edition

The first definitive and official career spanning release, fully endorsed by Burt, featuring six thematically arranged compilation discs:

- Disc 1 Magic Moments (1952 – 1962)

- Disc 2 There’s Always Something There To Remind Me (1962 – 1965)

- Disc 3 Let The Music Play (1966 -1965)

- Disc 4 That’s What Friends Are For 1973…

- Disc 5 Burt plays Bacharach

- Disc 6 Bacharach meets Jazz

Complete with a forty page book with liner notes from Robert Greenfield and additional images, this is a ‘must have’ deluxe box set and competively priced.

For non obsessives, there’s a 2CD collection featuring the most obvious entries from the career spanning 6CD box set and includes over thirty of his biggest hits.

Recommended viewing

Elvis Costello & Burt Bacharach – Because It’s a Lonely World (1998)

Documentary charting the development of the ‘Painted from Memory’ album, Bacharach’s first in over twenty years. Working with Elvis Costello, the pair originally collaborated on “God Give Me Strength”, a commission for the 1996 film Grace of My Heart, directed by Allison Anders and starring Illeana Douglas. Extending their partnership further, the pair co-wrote a complete collection of fresh compositions, notably “I Still Have That Other Girl”, which won a Grammy Award in 1998 for “Best Pop Collaboration with Vocals”.

Recommended reading

Anyone who had a heart : My life in music (Burt Bacharach with Robert Greenfield) 2013

Reviewing his autobiography in the British Daily Mail, Marcus Berkmann was moved to reflect on the composer’s treatment of his daughter, describing it as careless and controlling in equal measure and that his ex wife Angie Dickinson, had clearly never forgiven him. Then, venturing onto the very deepest of analysis, the reviewer wonders whether Bacharach himself might not feature somewhere on the autistic spectrum since empathy is clearly not one of his strong points and there appears to be an obsessive quality both to his perfectionism as a songwriter and the rituals with which he fills his life.

Burt Bacharach: Song By Song – the Ultimate Burt Bacharach Reference for Fans, Serious Record Collectors, and Music Critics(Serene Dominic) 2010

Burt Bacharach has written the music for over 700 published songs, which have been recorded by some 2,000 artists, from Frank Sinatra and Elvis Presley to The Beatles and The Supremes. ‘Song By Song’ is a scholarly work, a more engaging read than any casual browser might expect, thanks in part to the writer’s indefatigable zest for sifting arcane facts and integrating them into a more mainstream text. ‘Song-by-song’ journeys through Bacharach’s vast recorded oeuvre, from Nat “King” Cole’s little-known 1952 version of ‘Once in a Blue Moon” to Burt’s more contemporary collaborations with Elvis Costello, Lyle Lovett and Chicago.

Comments

Last Update : 9/3/24

Burt Bacharach was a classically trained pianist whose songs and compositions have been recorded by the most influential artists of the twentieth century. Over the past seven decades, his legendary songwriting has touched millions of devoted listeners all over the world.

He wrote more than seventy Top 40 hits and won three Academy Awards, eight Grammys (including one for lifetime achievement), an Emmy, a Tony nomination, and received the prestigious Library of Congress Gershwin Prize for Popular Song. “What the World Needs Now is Love,” “Raindrops Keep Fallin’ on My Head”, “That’s What Friends are For” and “Walk on By” number amongst his vast catalogue of evergreen standards. In 2007 however, he was compelled to face up to one of life’s maxims, when his 40 year old daughter committed suicide. Truly – no-one has it all.

Nikki Bacharach had Asperger’s syndrome, a neurobiological disorder first described in 1944 by a Viennese doctor, Hans Asperger, yet widely unrecognised until the mid-1990s. It’s characterized by normal and sometimes extremely high I.Q., deficiencies in social skills (stemming from an inability to read nonverbal cues), extreme literal-mindedness, difficulty handling changes in routine, and a tendency to become obsessed with things. Another feature is extreme sensitivity to noise, which especially plagued Nikki, who was tormented by the sounds of the omnipresent helicopters flying over Los Angeles. Her mother, the actress Angie Dickinson, to whom Bacharach was married for ten years, recalls her daughter repeatedly requesting that the air-conditioning be turned off because she found it too noisy. “It’s horrible and I dread every single day, except Sunday.” “She just went crazy with it,” Dickinson says. “Believe me, we played music, but when the helicopter came over, we jacked up the Pavarotti.” Dickinson even thought about selling her beautiful home in Coldwater Canyon and finding a quieter spot.

Some experts consider Asperger’s a high-functioning form of autism, and in fact many people with it do manage careers and families of their own, but Nikki was also impeded by diminishing eyesight, a result of her premature birth. The greatest trial of her life, she firmly believed, was her hospitalization when she was fourteen, a period of incarceration that would last ten years, and significantly before Asperger’s syndrome had yet been identified. Hospitalization is not a prescribed treatment for the disorder, yet Bacharach sanctioned her stay, seemingly uncomprehending of her ailment. Nikki held her father responsible and Dickinson adds “I don’t want to be unkind to Burt because I’m very respectful of him, as a person and an artist, as a former husband and as a father to Nikki, but he had no real connection with her. She was too difficult for him, but it was his loss. He put her in a hospital, and it was the worst thing you can do. He had the wrong goal in mind: he thought that she was just a difficult child, and I was just a terrible mother, indulging her. He didn’t know there was actually a syndrome. He thought, Just get her away from Angie’s indulgence and she’ll shape up. But, of course, the doctors didn’t have a clue. He does regret it,” she adds wistfully, “and he has said, ‘I’m terribly sorry. Had I known, I never would have done that.’ Nevertheless, it destroyed her. Nikki had a difficult time forgiving her father, because holding on to ideas and emotions is part of the syndrome”.

Speaking to Vanity Fair in 2007, shortly after her daughter’s suicide, Dickinson confirmed that Bacharach had been supportive, making repeated attempts to move back into his daughter’s life, but that Nikki “resented him so much, she wouldn’t let him back in. He kept telling her, ‘I’m sorry.’ But once she got on a thing, it was very hard. We were once coming up with titles for a book, and she floored me with the title she came up with: I’ve Never Healed from Anything. Whatever she’d been wounded by, she never healed. It’s a terrible syndrome because they can’t let go. Medication can slow it down a little.”

Nikki had her own apartment in Los Angeles but spent a great deal of time living with her mother, skinny-dipping in their pool, watching DVDs at home or going to screenings at the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Like her mother, she loved the movies. “I love her career,” Nikki would say, going on to recite dialogue from her favorite Angie Dickinson film, Big Bad Mama.

Dickinson was clearly proud of her daughter, and, as she says, “You wouldn’t have wanted to see her gifts ignored.” Like a lot of people with Asperger’s, Nikki was extremely articulate, even lyrical. She once described listening to one of her father’s songs as “going to heaven on a velvet slide.” I miss Nikki so much, but it was her decision. The world was too harsh a place for her.”

The then 84-year-old award-winning music composer published his autobiography in 2013. In his book “Anyone Who Had a Heart: My Life and Music” (Harper), he discussed the death of his daughter.

“It was very tough because I had to revisit what that period was and go deeper into it,” he said of his daughter Nikki’s premature birth, years of emotional issues, and eventual suicide at the age of 40.

“(Nikki) was one-pound, 10 ounces at birth, you should know the deck is stacked against you then,” Bacharach said.

According to her father, she grew up with emotional issues, which he later found out was an undiagnosed case of Asperger’s syndrome (the autism spectrum disorder is a relatively new diagnosis.)

“Nobody said she’s got Asperger’s or she’s got autism. (They said) she’s just got behavior things,” he said.

But after suffering for so long, he never imagined she would actually kill herself.

“It’s like the boy who cried wolf. Somebody who says, `I can’t stand it. The helicopters are making too much noise and the gardeners and the blowers are making too much noise and if they don’t stop I’m going to kill myself,’” he said, his voice cracking. “And you hear that enough and you know it’s never gonna happen and then one day she just goes and kills herself.”

She committed suicide in her southern California apartment.

“When she did kill herself she did it alone, Textbook 101. Bag over her head. Alone. Kind of brave I guess for somebody who (was) scared of so many things and (she) left a note to me.”

He later realized that the signs were always there, but thought that the strong relationship she had with her mother would prevent it from ever happening.

“They had a very connected, symbiotic relationship,” he said, adding, “We all did everything we could. I did what I thought would be the right thing and it wasn’t the right thing and I was just trying to get her better.”

Bacharach was referring to the painful decision to send her away to a special school. He feels he made the decision because Nikki was not properly diagnosed. Because Nikki spent some time away from her mother, he feels she always held that against him.

“There was always that resentment that I kind of imprisoned her and the last thing in the world you know,” he said. “I wish somebody would have just said, you’re not going to heal her, let her be.”

Asperger’s syndrome is a pervasive developmental disorder on the autism spectrum. People with Asperger’s often have high intelligence and vast knowledge on narrow subjects but lack social skills.

With his family struggles hidden from the world, Bacharach continued to make great music.

“I was always able to alleviate the noise, some of the noise with what was going on with Nikki becoming a Sikh, or whatever, because I would go to my music. … It was during that time I scored `What’s New Pussycat,’ I scored the first `Casino Royale.’ I would get engrossed in my music because there’s no other way for me.”

Bacharach is still haunted by her death. When they discovered the body, Nikki had left him a note.

“I know exactly what’s in the note. I never read the note. I never will,” Bacharach said as his voice cracked. “There is no need to read it. I already know what she said.”

If it’s true that for decades, breaking up relationships was a specialty of Bacharach’s; many of the women in his life, including his first three wives, describing him as exuding a combination of ambition, ambivalence and arrogance, then life has truly returned to more than bite him on the hand.

He is undoubtedly a ‘driven individual,’ his second wife, the songwriter Carol Bayer Sager, recalling Bacharach’s approach to his craft in a 1996 BBC documentary_ “This is Now.”_

The opening line to his 1986 global hit ‘That’s what friends are for,’ performed by Dionne Warwicke and friends, is a case in point. His pursuit of a lyrical content that will perfectly match the metering of the song, borders on fastidiousness in its most extreme form.

The original recording, featuring Stevie Wonder on harmonica, can be located at:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=66Qkf2Jm6pc

The opening line reads as follows:

‘And I, never thought I’d feel this way’.

Observe the notation carefully, the 16th note rest illustrated by the coma after the word ‘I’.

Bacharach agonised for an hour in his music room, his wife seemingly content to settle for the originally proposed

‘I never thought I’d feel this way’.

Sayer admitted the tortuous process was maddening, being acutely aware as she was, that millions would singularly fail to observe the added inflection yet she would ultimately concede thatr ‘he was right, and I finally wrote ‘and I’.

The finished version implies an eavesdropping session on a private conversation in progress between close friends, whilst the discarded original suggests a worldwide proclamation, the intimacy of the moment clearly discarded. If the first scenario suggests a strained relationship, a friendship taken for granted; the alternative indicates communal spirit in its purest and most joyful sense. Whatever the protracted process, the song restored his compositional mojo, after the wilderness years of the late 70’s.

His second wife is rather reflective when discussing her time with Bacharach. As Bayer Sager puts it: ‘What I now realise is that nothing changes with Burt when he changes wives. The only thing that changes is the wife, but his routine remains the same’.

I find this comment very illuminating as it goes to the very heart of relationship issues as I see it. Perhaps it is a fundamental inability to modify one’s characteristics that ensure a seemingly never ending cycle of brief liasons and failed medium term relationships. It becomes apparent to me that those very qualities in our partner that once appeared so unusual, left field, idiosyncratic and therefore greatly appealing, become, given sufficient time, a fundamental source of irritation. Of course, it is also important to reflect at times like these on just how irritating we have become ourselves. Could we describe ourselves as pleasant and agreeable to live with? How considerate are we? Would we rush to regale the woes of the day to a new romantic liason in the same downbeat manner as we would our longstanding marital partner? How might we vary the timbre of our voice and general demeanour? Would we elect to say anything at all? In the final analysis, we present one image of ourselves for public consumption, but the reality of how we are viewed by the few individuals who are ‘intimate’ with us, may well be greatly at variance with this ‘agreeable facade’. Focusing purely on what attracts us to a person in the first place is an enjoyable yet ultimately flawed line of thinking. I’ve lost count of the amount of times I’ve overheard people eulogising about their new partner only to castigate them a year later after they’ve broken up. What is one to make of all of this? Is the perception of ourselves by others merely dependent upon living up to their expectations? Is the expectation a realistic one based on forthright honesty? I have no definitive answers but I am moved to recall one of my late father’s observations on life when he would counteract my mother’s surface level assessment of someone she had only just met, by adding the one liner ‘Everyone’s lovely until you really get to know them’. I could never avoid laughing much to my mother’s chagrin.

If Bacharach was therefore routinised in his lifestyle, then his near obsessive pursuit of professional excellence, a work ethic that any partner might well have found intrusive to a harmonious relationship, was temporarily ‘overlooked’ as the obvious material trappings of this dedication, in addition to his fame and good looks, all combined to make an irresistible catch. Unfortunately, each subsequent woman to share his life still found, as indeed did her predecessors, that her man would vacate the matrimonial bed in favour of the music study at three in the morning when his muse was active and a compositional idea began fermenting.

he would die of natural causes in early 2023 at the grand old age of 94.