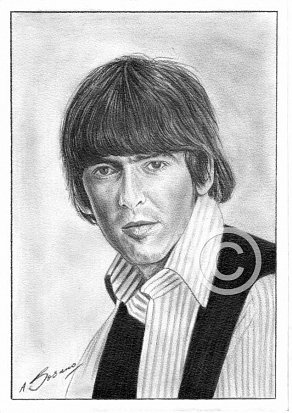

George Harrison

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £20.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £15.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

All Things Must Pass (1970)

Harrison might have been inclined to jetison the Spectorised ‘wall of sound’ for its 30th anniversary re-release, but with the basic tracks recorded “wet,” *** there was little he could do. And perhaps that’s just as well for “All things” is a period piece, but no less grandiose for it.

Connoisseurs still widely regard the quiet one’s sprawling work as amongst the top five or six solo Beatles albums – no mean feat 45 years after its release. It’s a magisterial work, lush and epic in its sonic wash, soaring and ultimately engaging. When I listen to the album, I play it all no matter what I’m doing.

The album would get a second sound upgrade in 2014 as part of the “George Harrison – The Apple Years 1968-1975” box set, but not significantly rewarding enough to tempt original punters to shell out again.

Melody Maker’s Richard Williams summed up the surprise many felt at the so-called “quiet Beatle’s” transformation: All Things Must Pass, he said, provided “the rock equivalent of the shock felt by pre-war moviegoers when Garbo first opened her mouth in a talkie: Garbo talks! − Harrison sings!

The “Apple jam” disc was always superfluous – if there was ‘artistic motivation’ behind its release, then the former Beatle never revealed his thinking at the time in subsequent interviews. Fortunately, as part of a double disc CD package, visitors can simply call time on the listening experience after track nine disc 2 “Hear me Lord.”

***Dry simply means without any effects. Wet means with effects. Reverb is usually the effect/plugin that is used to control the front to back placement in a mix. The dryer the track – less reverb – the more forward it will be in the mix. Conversely, increasing the amount of reverb – making it ‘wetter’ – will send it towards the back. Tracks recorded wet cannot be separated from their ambient reverb for a revised mix at a later date.

George Harrison (1979)

Hot on the heels of disco, punk would be a cultural shift too far for Harrison. Adopting a pragmatic view – only a retired Lennon would escape the wrath of the new rebellious young – the ‘quiet one’ simply slipped abroad in 1977 to follow the formula 1 circuit whilst stockpiling new compositional ideas. There appeared little point in competing and in any event, Harrison was never one to pursue trends in order to remain ‘hot.’

With punk dissipating even more quickly than he could have possibly anticipated, Harrison would reconvene at F.P.S.H.O.T in the summer of ’78 with his usual crew, but also Russ Titelman, a producer clearly sympathetic with his client’s muse.

Fleshing out the studio attendees would be Eric Clapton and Stevie Winwood (guitar and clavinet on “Love comes to everyone” in addition to Gary Wright who would co-author the album closer, “If You Believe.”

Apart from the obvious ’45 “Blow Away”, which featured a breathtakingly beautiful double tracked slide intro from Harrison, the album is awash with serenely crafted ballads and medium paced numbers.

‘George Harrison’ is refreshingly lighthearted. The austere, proselytising tone on ‘Material World’ is thankfully long gone – God, how that album pissed off NME journalists Roy Carr and Tony Tyler – and the singer sounds more like a happily eccentric gentleman/mystic than a devout Krishna advocate.

Replete with breezy love songs to the deity and to women — to Harrison, the two seem almost interchangeable – the lyrics, whilst occasionally lapsing into fulsome syntax (“Breath it’s always taken when it’s new/Enhance upon the clouds around it”), most of the numbers are relaxed and playful. “All I got to do is to love you/All I got to be is, be happy,” he sings in “Blow Away,” the LP’s strongest track and the one that best typifies its spirit.

The arrangements are the most concise and sprightly to be found on any Harrison record. “Not Guilty,” “Here Comes the Moon” and “Soft-Hearted Hana” -a paean to Harrison’s reacquaintance with magic mushrooms – transport us back into psychedelic lotus land, but their tone is so airy and whimsical that the nostalgia is as seductive as it is anachronistic.

Only “Faster” lets the collection down. Dedicated to, and equally inspired by the ex-Beatle’s penchant for motor racing, the song suggests much more than the writer can deliver. Suitably adorned with stereo panned high speed formula one racers, the chorus revs up the proceedings but the verses labor in second gear, Harrison’s musical camshaft seemingly bedevilled with mechanical problems.

Melodic hooks abound, whilst George’s slide guitar playing adds sublime touches throughout. The album would achieve gold status in the States, ‘Blow Away’ also scoring well on the Billboard and Canadian charts, yet Harrison’s increasing efforts would be directed towards the film industry, having formed Handmade Films in order to help his friends in Monty Python complete ‘Life of Brian.’

If Spector’s wall of sound (“All Things Must Pass”) is not your thing, and Jeff Lynne’s signature production (“Cloud Nine”) leaves you cold, then this eponymously titled album remains the best example of Harrison at his purest. Perfect for relaxing poolside with a cool drink, its deft combination of the quaint and the slick made the ’60’s seem a trifle less remote for a Britain emerging from the winter of discontent.

Cloud Nine (1987)

Harrison’s last million seller, and a welcome return to form.

Teamed with former Electric Light Orchestra front man Jeff Lynne, the pair would craft a radio friendly concoction, fusing Harrison’s signature sound with Lynne’s richly produced sonic landscapes. Suitably buoyed by the experience of being in a ‘band’ again, the former Beatle would embark on a large scale promotional campaign that would last nearly four months. Amply rewarded with a top ten album on both sides of the atlantic, his first number one single in the US and Australia in nearly seventeen years and widespread critical acceptance, Harrison’s career would gather pace, initiating a productive phase in recording and live performance that would culminate in his April ’92 Royal Albert Hall concert – a performance I was fortunate enough to attend.

http://beatlesnumber9.com/creem.html

http://www.gretschguitars.com/features/georgeharrison

Brainwashed (2002)

A low key ‘au revoir’ from that most reluctant of superstars, “Brainwashed” finds the ‘quiet one’ still searching for life’s answers on this posthumous release.

“I’m a living proof of all life’s contradictions,” Harrison admits with a dash of mirth in his low, sandy voice in “Pisces Fish,” one of the eleven original songs on his final studio album. “Lord, we got to fight/With the thoughts in the head, with the dark and the light,” he sings on the first track, “Any Road,” with zero irony. But as a songwriter and guitarist, Harrison never lost his gently intoxicating way of posing big questions about guilt and transcendence. If the lavishly orchestrated hymns on All Things Must Pass (“My Sweet Lord,” “What Is Life”) were his idealisation of life beyond material form, ‘Brainwashed’ is a warm, frank goodbye, a remarkably poised record about the reality of dying, by a man on the very edge. Fear and acceptance run together in these songs, anger as well as serenity. Most pleasingly, there’s much of his distinctive guitar work to delight in – that distinctive and melodious slide on “Stuck inside a cloud” and the gorgeous “Marwa Blues,” arpeggiated chordal work on “Run so far,” and an affectionate nod to Hoagy Carmichael on “Rockin’ chair in Hawaii,” complete with hula-blues dobro. The ukelele driven “Devil and the deep blue sea” reminds us one last time of his unique interpretative skills, and the all covers album he would sadly never make.

Harrison died before he could finish “Brainwashed,” but his co-producers — son Dhani and ELO’s Jeff Lynne — would complete the album with impressive sensitivity, to the point that he still feels immensely present: strong and centered in his singing over the lazy rivers of strum, uncrowded by excess reverb or overcooked choruses. Vocally, he actually sounds younger and more engaged than he did in middle age on half-hearted LPs such as Dark Horse (1974) and Gone Troppo (1982). He puts real spring into the Zen lesson of “Any Road” — “If you don’t know where you’re going/Any road’ll take you there” — along with long, gleaming curls of slide guitar. And there is a plaintive wrench to his hindsight in “Looking for My Life” — “Oh, boys, you’ve no idea what I’ve been through” — especially when the background harmonies pull out and Harrison is alone and close to the mike.

Lynne’s co-production work is tastefully understated, and Harrison’s droll humour is well to the fore.

In fact, he makes a pointed allusion to cancer and his impending fate with a dry reference to “my “concrete tuxedo” in “P2 Vatican Blues (Last Saturday Night),” whilst in “Looking for My Life,” there’s candid shock at the unfolding events: “Had no idea that I was heading/To a state of emergency.”

The Ex-Beatle could over-proselytize at times, and the album does end on a hectoring note with the title track, a literary rail against the social ills of the 21st century. Still, the musical coda – an old tape of Harrison performing an Indian chant, suggests that there was little bitterness or regret in his music — mostly acceptance, anticipation and big twang. It is a fine, enchanting epitaph for a man who, to the end of life, believed rock & roll was heaven on earth.

George Harrison interview with Alan Freeman (BBC Radio One) 1974

Harrison sat with Alan “Fluff” Freeman on October 18th, 1974, to offer up some personal insights into the working dynamics of his old band, his religious convictions, and songwriting, the interview suitably top and tailed with some ‘off the cuff’ acoustic workouts.

Recommended viewing

George Harrison - Living in the Material World (2 DVD Set)

Previously unseen private letters, home movie footage and intimate personal recollections of George Harrison counterpoint politically correct public perceptions of “the quiet Beatle” in Martin Scorsese’s much vaunted documentary..

For the uninitiated, revelations include the fact that Harrison’s widow, Olivia, struggled to keep the relationship with her wayward husband on track. In the film, Eric Clapton also talks about how he felt consumed with envy as he fell in love with Pattie Boyd, Harrison’s first wife.

Scorsese, who had previously focused his camera on musical subjects, from his history of the blues to a concert film of the Rolling Stones and an acclaimed study of Bob Dylan, ‘No Direction Home’, here sheds light on the self-confessed “dark horse” Harrison. ‘Living in the Material World’ shows a man who – as well as being the stylish hippy of popular perception – had a caustic wit and a talent for deep friendship as well as an abiding obsession with his music.

Olivia Harrison, who produced the film with Scorsese and allowed unprecedented access to the family archive, talks candidly about her late husband’s “challenging” attitude to other women, and about the stranger who broke into the couple’s home and nearly ended Harrison’s life shortly after he had recovered from the first bout of the cancer that would eventually kill him.

She reveals that, although she and Harrison “seemed like partners from the very beginning” and shared a strong interest in meditation, their marriage survived a series of “hiccups”. “He did like women and women did like him,” she says. “If he just said a couple of words to you it would have a profound effect. So it was hard to deal with someone who was so well loved.”

Paul McCartney, who would practice monogamy with first wife Linda almost as a religious calling, speaks about his old friend’s appreciation of women: “I don’t want to say much, because he was a pal, but he liked the things that men like. He was red-blooded.” His embarrassment is palpable, the interview an almost touching admonishment of a close friend.

Interviews with Phil Spector, who produced Harrison’s first solo work, and with Sir George Martin reveal Harrison’s central concern with music. Spector remembers an emotional intensity and an attention to detail. “Perfectionism is not the word. It went beyond that.”

Harrison’s widow says that his most important relationships were conducted through music and recounts that some of the lyrics to the song ‘I’d Have You Anytime’, written with Bob Dylan, were addressed to Dylan himself, whom Harrison felt had retreated from their friendship.

Elsewhere, Eric Clapton talks about the Camelot-like world of The Beatles, and of feeling like he was an envious Lancelot. “I had become more and more obsessed with [George’s] wife, Pattie,” Clapton admits, describing how he confessed to his friend, “who was very cavalier” about it, almost giving him “carte blanche.” Clapton adds: “To be honest there was a lot of swapping and fooling around.”

Interviews with Eric Idle and Terry Gilliam confirm Harrison’s crucial role in funding the Monty Python film ‘Life of Brian’ by mortgaging his home. Harrison, through HandMade Films, went on to produce other leading British films such as ‘The Long Good Friday’, ‘Mona Lisa’ and’ Withnail and I’.

In a heartwrenching finale, Ringo Starr is brought to tears on screen by the memory of his final conversation with Harrison who, dying in a Swiss hospital bed, still managed a bleak joke. Starr had to leave because his daughter was undergoing emergency brain surgery in Los Angeles.

“George said: ‘Do you want me to come with you?’ They were the last words I heard him say.”

Scorsese nearly gets it completely right, his film tight-walking the duality of Harrison’s musical and spiritual worlds with astute sensitivity. Unfortunately, he chooses to overlook virtually Harrison’s entire Warners catalogue including the intensely personal songs found on the posthumous release “Brainwashed”, many recorded when his time was short. Volume three please Mr Scorsese.

Recommended reading

I Me Mine

The closest thing to a Harrison autobiography without ever really getting close, ‘I, Me, Mine’ was originally published in early 1980 as a hand-bound, limited edition book by Genesis Publications. Boasting a mere 2000 signed copies, with a foreword by Beatles publicist and longstanding friend Derek Taylor, the Genesis limited edition sold out soon after publication, and was subsequently published two years later in both hardback and paperback in black ink by W H Allen in London and by Simon and Schuster in New York.

Lennon took offence at the book, telling interviewer David Sheff that “I was hurt by it … By glaring omission in the book, my influence on his life is absolutely zilch and nil … I’m not in the book.”

The essence of Lennon’s displeasure was a musical one, yet eight years after his senseless murder, Harrison remained unrepentant, telling the BBC’s Selina Scott that John had never acknowledged the reciprocal nature of their relationship. Worst of all, the pair had not reconciled before the assassination, whilst McCartney at least, had discovered a safe middle ground upon which to conduct lengthy transatlantic phone calls with his old friend; the conversations focused on raising children, cats and domestic chores.

Comments

Last update : 1/8/15

It is now more than a decade since George Harrison lost his battle with cancer at the age of 58. Like millions, I knew the news of his demise was coming, and yet somehow for a man who was amongst the four most famous men on the planet earth between 1963-1970, the illness ravaging his body seemed somehow almost statistically mundane.

Surely, he was deserving of a more dramatic finale? – not of course any repetition of the violent manner of Lennon’s passing, but something somehow intensely spiritual, perhaps a sudden passing on the hills of the Ganges. And yet, it was precisely this spirituality with which he chose to deal with that insidious disease that can indiscriminately ravage any of us at anytime…….

Despite the millions of printed words and interviews with key personnel involved in their tumultuous lives, no definitive insight has ever been offered as to why Harrison would have remained such an essentially morose man. After all, becoming the third most popular musician on the planet earth hardly seems a reason for such prolonged resentment. In contrast, and with the exception of his decade long battle with ‘serious sauce addiction’, his close friend Ringo Starr has remained eternally appreciative of the cosmic joke life played on him in 1962. He retains a cheerful acceptance of life’s whimsy, essentially happy enough to count his blessings for a pampered life that most goofballs could only dream about. That is not to denigrate his central role as the musical heartbeat of the band, nor his soothing emollient personality that on many an occasion, interceded effectively to calm the barbs flying between his ‘three truculent brothers’. In Harrison’s mini-autobiography at the front of ‘I Me Mine’, he seems mostly unhappy about the travel indignities he suffered during The Beatles years. In Martin Scorses’s HBO documentary, “George Harrison – Living in the Material World” (2011), the director plays the price-of-fame card heavily. “It’s fun,” Starr says, “early on. But then you want it to stop, and it never does.”

One pivotal month in Harrison’s life – January 1969 – perhaps more than any other, pinpoints various character flaws that contributed so much to his general dissatisfaction with life. Like any researcher, I can only stand by the authenticity of an incident which occurred at Twickenham film studios; as for what was concurrently happening in his private life, we have only the testimony of two women, as Harrison himself is no longer around to defend his case. Nevertheless, based upon numerous recollections of musical collaborators, we can safely assume both events occurred.

According to biographer Graeme Thomson (“Behind the locked door”- Omnibus Press 2013) Charlotte Martin was involved in the late 60’s with Eric Clapton, and after the relationship broke up, the french model stayed briefly with friends Pattie Boyd and George Harrison at their Kinfauns bungalow in January 1969, before returning to Paris to continue her professional work. Pattie had successfully modelled in the mid 60’s, but after her marriage to the “quiet Beatle”, her boorish husband’s northern roots had eventually ‘seen off’ her career potential in favour of domesticity.

Charlotte allegedly had an affair with George, which devastated Pattie because she considered her guest a friend. In her memoir, ‘Wonderful Tonight’, Boyd says Harrison was highly controlling as a husband, pursued other women, lost interest in her, and then spent all his time puttering around his estate and filling it with Hare Krishna families. Did she conveniently clear the pitch for her husband by vacating the matrimonial home for hours, even days on end? This seems unlikely, as she would effectively have been playing hostess. Whatever the background, Harrison’s mind would have been in some turmoil as he reported back for duty at Twickenham film studios to face his old musical nemesis – the overpowering and continually hectoring Paul McCartney.

By 1969, ‘George was terribly unhappy,’ says Boyd; ‘The Beatles made him unhappy, with the constant arguments. They were vicious to each other. That was really upsetting, and even more so for him because he had this new spiritual avenue. Like a little brother, he was pushed into the background. He would come home from recording and be full of anger. It was a very bad state that he was in.’ Among the extensive interviews that punctuate the HBO documentary ‘Living In The Material World’, the bluntest assessment of George comes from Ringo Starr: “He was a bag of beads and a bag of anger.” This begs the question as to why he singularly failed to channel his resentment into something positive? After all, The Beatles as an entity, were like no other musical act. The group, uniquely, were four corners of a square and unlike so many other acts, could not have continued with any element missing. Storming out of Twickenham after one row too many with Paul, his sardonic conciliatory “see you round the clubs” fell on deaf ears with Lennon, who would later suggest bringing in Eric (Clapton). The public would never have stood for it, and had Harrison simply thought long and hard enough about it, then he could have safely dictated some improved terms for himself within the group. Instead, he would simply choose to be the voice of both dissent & disinterest, vetoing a return to live work in much the same manner as he had championed the group’s withdrawal from the stage two and a half years earlier. More immersed in Eastern religion and musical ragas than McCartney’s vision for ‘Pepper’, he had contributed very little to the group’s summer of love opus.

In the years following the group’s demise, Harrison would promulgate the notion of an overrated band forever associated with a handful of pleasant tunes, and an experience that had forever stunted his musical growth. Detractors and non-Beatle believers might well concur on both counts, and yet the truculent one’s motivation for such press utterances was clearly inextricably bound to his droll Liverpudlian humour. Railroaded into a reunion project with Paul & Ringo in 1994/95 – “The Beatles will never reunite as long as John remains dead” – Harrison was by now strapped for cash, if such a situation can exist for any man down to his last £10m. After all, taking his erzatz colleagues for a spin in his new £500K priced Mclaren F1 supercar before filming a two hour acoustic session for the cameras, hardly suggested a man facing austerity squarely in the eye.

Locked into a £16m legal battle with his business manager Denis O’Brien’s Euro-Atlantic company, the former Beatle’s business naivety had once again got the better of him. Acknowledging the continuing commerciality of his old group, Harrison’s financial woes sent him silently kicking and screaming into a new Beatles project. Suitably fortified by the presence of old mate Jeff Lynne in the production chair, lest McCartney’s single-mindedness prove as overbearing as ever, artistic differences would be set aside. As it would happen, Lynne was focused on impartiality – much to McCartney’s relief – and the February ’94 session progressed well. The repartee between the three was reportedly hilarious, and Harrison’s input was considerable – vocals on an abbreviated four line bridge, slide guitar solos during the intro and twelve bar central break plus a Formby inspired ukelele outro. Whatever the critical backlash – McCartney aptly referring to the resultant press reviews as ‘anticipointment’ – “Free as a bird’ was nonetheless a bona fide entry in The Beatles cannon. Lacking that all important star quality to make it a legitimate ’45 single release, yet an infinitely more rewarding listening experience than several historic album tracks – ‘Wild Honey Pie,’‘Mr Moonlight,’ ‘Revolution #9,’ ‘Blue Jay Way,’ ‘All together now’ to name but five – there was still sufficient magic to warm the hearts. McCartney’s freshly minted verse, his Wal bass five string bottom end, Harrison’s plangent guitar lines, Lennon’s distinctive piano work and some glorious ‘Abbey Road-esque’ vocal harmonies, all contributed to a warmly evocative reminder of their collective genius. Failure to comprehend the technical shortcomings of Lennon’s cassette based crude home recording – vocal and piano irrevocably locked together, wayward time and therefore no audible ‘click track’, non existent noise reduction – are reasons enough to miss the technical marvel that is ‘Free as a bird’. Internal affairs were not aided by Harrison’s assertion that ‘John’s writing was going a little off at the end’, yet his adroit and melodic solo on ‘Real Love’ – the second reunion single again fashioned from an old Lennon composing tape – was evidence of his sole opportunity within the group, to inject creative input into the February ’95 sessions. A fully realised composition, unlike ‘Free as a Bird’, Paul & Ringo would contribute little more than basic tracks. What then, did Harrison have to complain about? Nevertheless, he would veto any suggestion of a another reunion single for Anthology 3, the sessions for “Now & Then” reportedely nixed within a solitary afternoon. Continuity was accordingly lost.

Interviewed by Guitar Player magazine in the early 90’s, he was less than complimentary about McCartney’s bass playing on “Something,” describing the part as ‘busy.’ I have personally recorded a sixteen track cover of the song, and can only assure my readers that the part is sublime, testimony indeed to Paul’s ability to temporarily bury his ego for the greater good of a classic compositional work. There’s just no pleasing some people…..

Harrison was a Pisces, and at times, Pisceans have difficulty distinguishing fact from fantasy, tending to get caught up in their dreams and views of how things should be. It is said that they wear rose-colored glasses, fearing that their pleas aren’t being heard. This often leads them to lapse into melancholy and, worse, the kind of pessimism that leads to procrastination and lethargy. At times like this, Pisceans would be wise to take time for themselves, the better to find their centre once again. Many Pisceans also immerse themselves in the arts and other creative pursuits as a centering mechanism, often displaying appreciable talent in these areas. Now, even if you’re not into astrology, (and I’m personally a disbeliever), the undeniable fact remains that many of the star sign summaries run uncomfortably close to our own true personalities. McCartney is a Gemini, a person who can easily see both sides of an issue – truly a wonderfully practical quality to possess. Less practical is the fact that any Piscean would be unsure which Twin was likely to show up half the time. More worringly, Geminis may not know who’s showing up either, which can prompt others to consider them fickle and restless. Whilst George and Paul were schoolmates from way back, artistic tensions between the pair were almost inevitable in later life. Whilst many biographers have discussed the band’s internal business squabbles and marital relationships as key factor’s in The Beatles’ disintegration, very few have analysed their musical differences and fewer still were afforded ‘fly on the wall’ status to offer first hand testimony. Anthony Fawcett was John & Yoko’s personal assistant and general factotum between 1968 and 1970, and in the autumn of 1969 was privy to an Apple board meeting between all four Beatles. On pages 95-97 of ‘John Lennon – One day at a time, A personal biography of the seventies’ (New English Library 1976), he recalls Lennon’s drive for superior album material suitably approved by all four members.

“It seemed mad for us to put a song on an album that nobody really dug, including the guy who wrote it, just because it was going to be popular, cause the LP doesn’t have to be that. Wouldn’t it be better, because we didn’t really dig them, yer know, for you to do the songs you dug, and ‘Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da’ and ‘Maxwell (‘s Silver Hammer’) to be given to people who like music like that, yer know, like Mary [Hopkin], or whoever it is needs a song. Why don’t you give them to them? The only time we need anything vaguely near that quality is for a single. For an album, we could just do only stuff that we really dug.”

Lennon unfortunately, was not preaching from the pulpit; his unwarranted, superfluous and wholly inappropriate “Revolution 9” on the White album, a clear indication of the internal strife within the group by the fall of ’68. More in tune with the Zapple audio collage albums he would release with Yoko, the other three were unhappy about its inclusion but Lennon’s wishes carried the day. Harrison’s ‘Not Guilty’ would be an early casualty, for reasons he would ackowledge at the meeting.

“I don’t particularly seek acclaim – that’s not the thing. It’s just to get out whatever is there to make way for whatever else is there. You know, ‘cause it’s only to get ‘em out, and also I might as well make a bit of money, seeing as I’m spending as much as the rest of you and I don’t earn as much as the rest of you!”

http://www.collectorsmusicreviews.com/harrison-george/george-harrison-nassau-coliseum-1974-off-master-idol-mind-imp-n-027028/

He would remain coy about his songwriting, vetoing a special segment about his craft in ‘The Beatles Anthology’ Tv series (1995). Such humility might have remained an object lesson for us all, provided the so called ‘quiet one’ hadn’t devoted so much time to bemoaning his ‘economy class status’ to anyone who would listen. If Lennon and McCartney were truly carving up the songwriting empire, then Harrison could have worked more closely with Dick James and his DJM empire in order to find willing artists for his freshly minted compositions. Instead, songs would be routinely treated as ‘cast-offs’, to be offered to friends without determining a realistic release date. Joe Cocker, for example, would sit on “Something” for two years, his eventual release following in the footsteps of the “Abbey Road” album. Whilst another early recipient Tom Jones, was similarly dilatory with “The Long & Winding Road” – the group had already secured a US Number One in June 1970 before his cover was issued – McCartney was ‘minting it hand over fist’ with none of Harrison’s cashflow concerns, so should he have been concerned? Not likely.

Ultimately, one cannot help feeling that Harrison was in fact, responsible for much of his own woes. If he truly was carried kicking and screaming into the “Anthology” project, then the precarious financial position in which he found himself at the time, was very much his own fault. Introduced by Peter Sellers in 1973 to the accountant Denis O’Brien, George would eventually hire him as his manager. “Due diligence,” on strict commercial grounds, was eschewed in favour of “gut instinct,” a rather less than reliable basis on which to make such an important decision, particularly in light of his previous association with the nafarious Allen Klein. Initially, all would go well, and O’Brien would enable Harrison to extricate himself from the tangled web that was Apple.

By 1978, with George wanting to help out the Pythons with ‘Life of Brian,’ O’Brien was an obvious adviser on how to proceed given his former life. HandMade Films was created, with George and Denis as partners (with George as majority partner) – George bankrolling it, and Denis in charge of the day-to-day. Unfortunately, their management agreement was not dissolved at this time. This meant that that there was no-one overseeing O’Brien’s actions at HandMade Films, although staff would observe the “Phil Silvers” lookalike banker bamboozling the guitarist on his his infrequent visits to the company’s office. This appeared to work well while HandMade Films remained the UK’s leading independent film production company, but by the early ’90s – and a series of unqualified commercial flops – the company was losing money. After one failure too many, Harrison sent the accountants in and started finding questionable use of expenses to bankroll O’Brien’s lifestyle, and profit/loss irregularities on various films – including some of their most successful.

Harrison, as majority shareholder, dissolved the partnership in 1993, and sold the company the following year. Nevertheless, he would continue examining the books and in 1995 launched a $16 million lawsuit against O’Brien in California, being ultimately awarded the sum of $11 million. Unsurprisingly – for this is how the plot invariably unravels – O’Brien, would simultaneously declare himself bankrupt in his home state, preventing George from collecting the money awarded in California. Harrison, by this time, was in the early stages of his cancer. Compelled to initiate a lawsuit to have the bankruptcy declared as nothing more than a legal manoeuvre, but fresh from lung surgery, he was unable to serve a deposition; an action interpreted as unreasonable by the judge. The case was thrown out, leaving the former Beatle with little more than a pyrrhic victory.

Under construction.

In response to the question, “The most underrated guitarist in history?” – Guitar World, 12 September 2016, joe Satriani was moved to say:

“George Harrison, without a doubt. Just think about this, here’s a young kid at the start of a movement. Not someone who ever thought he’d be a virtuoso on the instrument, he was an all-round musician, and he was destined to write two of the most popular Beatles songs of all time, ‘Something’ and ‘Here Comes the Sun.’ His guitar playing just got better and better, right up to his untimely death…”

“I want to shout this, I want to put this in capital letters – HE WAS ALWAYS, ALWAYS MUSICAL! Most people can get good physically on the guitar, it’s not really that hard, but to be musical? That’s the real trick. There are a thousand other guitar players that could play rings around George, but what have they played that you really keep in your heart?”