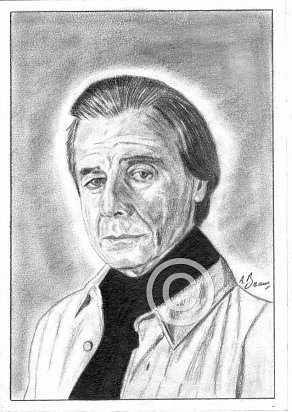

Lalo Schifrin

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

My Life In Music (4 CD Box set) 2012

A more than welcome retrospective of the great man’s work, this collection from Aleph Records catalogues the legendary composer’s career in film, jazz, and classical music. The set features music from three-dozen films, jazz and symphonic pieces composed by Schifrin, and unreleased music from films including ‘Charley Varrick’, ‘The Beguiled’, ‘Joe Kidd’, and ‘Coogan’s Bluff.’ Along with over five hours worth of music, the box set includes a forty-eight page book with archival photos and notes.

Pleasingly present amongst the more familiar works, are selections from his jazz and classical forays including work commissioned by Dizzy Gillespie, as well as the Grammy-nominated ‘Jazz Meets The Symphony’ series. His music is a synthesis of traditional and twentieth-century techniques, and his early love for jazz and rhythm are strong attributes of his style. “Invocations,” “Concerto for Double Bass,” “Piano Concertos No. 1 and No. 2,” “Pulsations,” “Tropicos,” “La Nouvelle Orleans,” and “Resonances” are examples of this tendency to juxtapose universal thoughts with a kind of elaborated primitivism.

A superb career overview but be warned – you may become as hooked as I did, and compiling Schifrin’s work is no mean financial task. A number of his film scores may be emblematic of a huge compositional talent, but quality runs consistently throughout his catalogue, whatever the level of public awareness.

Bossa Nova (New Brazilian Jazz) 1962

The Liquidator (1965)

The Cincinnati kid (1965)

Schifrin’s acclaimed soundtrack for the Steve McQueen movie, mixing in snatches of traditional jazz with light mood music.

The resultant album stands amongst the composer’s most successful film scores, both sales-wise and artistically.

The Venetian Affair (1966)

Cool Hand Luke (1967)

Bullitt (1968)

Soundtrack reviewed on the Steve McQueen page

Mission Impossible (1966 – 73)

Magnum Force (1973)

Enter the Dragon (1973)

The Eagle has landed (1977)

Recommended reading

Music Composition for Film and Television (Lalo Schiffrin) 2011

http://www.berkleepress.com/catalog/product?product_id=26861987

Mission Impossible: My Life in Music (Lalo Schiffrin) 2008

Mission Impossible: My Life in Music is the engaging autobiography of Lalo Schifrin, the musician, conductor, and composer of more than 60 jazz and classical works and over 100 film and television scores, including Bullitt, the Rush Hour series, Cool Hand Luke, The Dead Pool, Tango, The Fox, Voyage of the Damned, The Amityville Horror, The Sting II, and Mission Impossible.

Edited by Richard Palmer, this autobiography is a journey from Schifrin’s formative years in Argentina, to the classical and jazz atmospheres in Paris in the 1950s; and from his jazz career in the United States with Dizzy Gillespie from 1958-1963, to his development as a film and television composer from 1963 to the present.

Organized in eight parts, the book reflects on Schifrin’s cosmopolitan experience and provides impressions and vignettes of the extraordinary people with whom he worked. As a composer whose works bridge three main musical styles—jazz, classical, and film and television—his autobiography offers invaluable insights on all three genres, as well as politics, literature, and travel. This significant volume includes over 30 photos, appendixes listing Schifrin’s works, and a discography, as well as an audio CD featuring some of Schifrin’s greatest compositions.

Surfing

The definitive Lalo Schiffrin discography:

Comments

Last update: 11/8/15

Albeit the term “living legend” is as clichéd as a romance in Paris, Lalo Schifrin is exactly that and much more: pianist, composer, conductor, multi-Grammy winner, multi-Oscar nominee, film score genius and jazz musician. I can safely presume most visitors to my site will know the music but few will know the name. If we’re sure he drank Carling Black label to write the theme from “Mission Impossible,” then his vast catalogue of music suggests he’s been on the lager for decades!

Schifrin started his musical career – while studying law and music alike – in 1955 in Paris. After having played the piano with Astor Piazolla, he returned to his native city of Buenos Aires to form a 16-piece jazz orchestra that performed regularly on Argentinian television.

A meeting with Dizzy Gillespie resulted in a move to New York with Lalo Schifrin becoming the pianist and musical director for Gillespie’s quintet. He continued his work in TV, winning an Emmy for his radical re-arrangement of ‘The Man From U.N.C.L.E.’ theme tune, headed to Hollywood to compose the unforgettable theme tune to the ‘Mission: Impossible’ TV series, and scored classic Clint Eastwood films such as ‘Coogan’s Bluff’ and ‘Dirty Harry,’ not to mention Steve McQueen’s ultimate car chase movie, ‘Bullitt.’

Lalo Schifrin has since had an incredible career and over the last 50 years has provided music for over 100 movies, including classics like ‘The Cincinnati Kid’, ‘Cool Hand Luke’, ‘Che!’, ‘Kelly’s Heroes’, ‘The Eagle Has Landed’, ‘Enter The Dragon’, ‘The Amityville Horror’ – the list feels endless. Still composing and widely sampled by many of today’s producers (check Portishead’s Sour Times), Schifrin is widely respected throughout the musical world.

A late 2012 interview with the composer can be located at: http://www.jazzwax.com/2012/11/interview-lalo-schifrin.html\

Schiffrin’s early years were spent living under the fascist Peron regime in Argentina, his subsequent studies with Olivier Messiaen at the Paris Conservatory paving the wqay for his eventual flowering as one of Hollywood’s elite composers.

Schifrin left Argentina in 1952, returning four years later. By the early ’60s, however, he was solidly planted in Hollywood. The many military dictatorships that followed Peron’s made it impossible for him to attend his father’s funeral in Buenos Aires in 1979. By that time, Schifrin was under a death threat. This attitude from the Argentinian authorities is bewildering to say the least.

In the aftermath of World War II, Argentina’s door was open to a much more sinister group of people: Nazis and Nazi collaborators fleeing Europe in order to escape trial, or, one supposes, a bullet in the head for their war crimes, courtesy of Mossad, the Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations.” Shameful enough, but it gets worse. Despite an official position of neutrality, it appears that the Argentine government also actively supported Nazi Germany during the war, and that the offer of a safe haven to Nazis after the war was simply an extension of this support.

The main villain of this piece, perhaps unsurprisingly, was Juan Perón. Perón was sympathetic to the Nazi cause and in 1943 traveled to Germany to discuss the possibility of an arms deal between Argentina and Germany.

Investigators believe that following the war, a cabal of ex-Nazis and Nazi collaborators formed in Argentina and worked with the Perón government (he became president in 1946) to organize the emigration of hundreds, perhaps even thousands, of their kind to Argentina. Members of the group frequently travelled to Europe to look for and bring back more of the fugitives.

Whatever, the extent of this shameful period in Argentinian history, Schiffrin remained committed to his new life.

His father had been concertmaster of the Buenos Aires Philharmonic, and his uncle was principal cellist. His father thought young Boris – Schifrin legally changed it to “Lalo,” which is a nickname for Claudio, his middle name – might be better off as a classical musician. He studied with pianist Daniel Barenboim’s father, Enrique, who used to whack his fingers with a sharp pencil whenever he made a mistake. “That was the way musical education was at that time,” he said.

Although he later rebelled, Schifrin now seems grateful for the European musical education instilled in him by his father. When he was 9, he played Gershwin’s “Rhapsody in Blue” at the Teatro Colon with Erich Kleiber conducting. By then, he had already seen and absorbed operas, ballets and symphonies.

Looking back in 2008, at the time his autobiography was published, the Oscar winning composer recalled his father finally accepting his unusual hybrid career, which fused jazz with the European tradition of classical music. No doubt he would have been proud of his son’s four Grammy awards and six Oscar nominations, and that past honorees for the Temecula Festival lifetime achievement award had included Ray Charles, Karl Malden, Robert Wise and Etta James.

The composer said his father thought the tango was “vulgar,” but his natural feel for that sultry urban dance may have saved him from a night in jail. He was coming home late one night in Buenos Aires when two policemen spotted him.

“I had a case of LPs,” he recalled. “A whole case made for LPs was new in Argentina, and the police thought I looked suspicious, especially when they saw English labels and the word ‘jazz’ on many of them. They wanted to take me to the station. There was a cafe across the street with a piano, and I asked them to go there. I opened the piano lid and played a tango. They smiled and let me go.”

It was a close call, but other incidents, such as seeing Argentine soldiers goose-stepping in German uniforms, made it clear that the time had come to leave his beloved city. At the Special Section for Anti-Argentine Activities, his interrogator asked him why he wanted to leave Argentina to attend the Paris music conservatory. Schifrin answered: “Do you realize the honor it represents to have an Argentinean admitted to one of the most prestigious music schools in the world? I respectfully submit to you that this should be a cause for pride to our country!” His passport was signed and stamped.

Schifrin’s early exposure to organised religion was unorthodox. He grew up in a religiously mixed family, where Jews and Catholics intermarried. His father would take him to temple, and on Sunday mornings he would go to mass.

As he notes in his book, “All this was confusing to me since I was observing different rituals for the same God.”

His mother’s side was half-Jewish and half-Catholic but, he said, she “became Jewish.” There was a note of slight offense in his voice when he recalled how an aunt and uncle on his mother’s side once tried to convert him to Catholicism. Yet Schifrin has “great respect for people who believe sincerely in a religion and a God.”

Art, and particularly the art of music, forms a large part of Schifrin’s identity, but when asked whether he feels Jewish, he told a story.“Well, I have to tell you when I went to Israel for the first time I felt something when I saw that the police had the Star of David on their uniforms. I mean, this did something to me.”