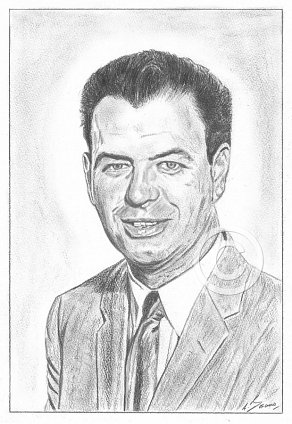

Nelson Riddle

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended reading

Arranged by Nelson Riddle (1985)

The definitive study of arranging by America’s premiere composer, arranger and conductor. A “must” for every musician interested in a greater understanding of arranging. Includes chapters on instrumentation, orchestration, his work with Sinatra, Cole and Garland and pictorial illustrations.

In his tutorial book, Riddle outlines the process of coming up with ideas for movie music. Anyone who has ever written music for movies, TV or commercials will recognise themselves in this situation:

“The arranger/composer for films needs to become acquainted with a few new tools in order to move comfortably in this medium, which differs considerably from the more or less straightforward approach toward writing for recordings.

“Having been assigned the scoring of a film, the first person the arranger/composer will meet up with will be the producer, the director, or both. These gentlemen will call the arranger/composer in for some discussions of what they expect to hear in the score, and due to exigencies of time, which usually are alarmingly present, they will want to show you their “baby”, the film. It is best to remember that, in all probability, both the director and the producer have slept, awakened, shaved, eaten all their meals, and have driven to the office thinking of very little else but this creation of theirs for several overcharged months. So it would be wise, as when a proud father flips a baby picture from his wallet, to try to register enthusiasm when seeing the film, lest they think of you as “cold”, unfeeling, and quite atypical of the audience they are striving to reach. This enthusiasm can be manifested by well-timed “ahh’s”, “ooh’s”, forced laughter and an occasional meaningful “grunt” of appreciation for all that is being dangled before your eyes.

“At the second running of the film, or the third, or occasionally (in a situation of near desperation) the first, there will be an attempt to “spot” the movie, the process of deciding which scenes of the film are to be scored and which are to be left alone to survive (it is hoped) on their own merit.

“The arranger/composer will be expected to contribute some intelligent input in this matter, and if he can assimilate the movie quickly enough and is able to speak in an authoritative manner, can usually make some of his ideas stick. It must be remembered, however, that spotting ideas arrived at with lightning-like genius may lose their cleverness upon further consideration, to the point where they prove totally impractical. By now these gems of insight may have found their way into the spotting notes (a secretary is usually present at each running) and from that vantage point loom as a fearsome hurdle to justify musically. Nevertheless, the musician, as the architect of this damnable blueprint, is committed to making it come to life. He can do that, or he can back out of the situation as gracefully as possible under the circumstances. A grim choice!

“It is occasionally better to let the producer or director do the leading for a while. This method affords the arranger/composer valuable time to think of what he is going to say and perhaps whip his ideas into a workable plan he can live with.

“He will also find at the session that no shortage of ideas exist in the minds of his two superiors. They, as stated before, have “lived” with this project for a considerable time and, based on some malevolent quirk of human nature, know their jobs inside and out, plus all there is to know about music!”

From “Arranged by Nelson Riddle”, ©Nelson Riddle, 1985

September in the Rain: The Life of Nelson Riddle (Peter Levinson) 2005

One of the more unexpected book purchases I have ever made. Published by Taylor Trade of Maryland USA, I would never have expected to locate this tome in a generalist UK retailing store but there it was, a single paperback copy at the knockdown price of £5.99.

The first-ever biography of the highly respected arranger in the history of American popular music. Based on more than 200 interviews with his closest friends, family, and colleagues, Levinson’s biography also analyses Riddle’s private life and the pressures that blew his marriage apart. There was criticism of this biography, most notably from Riddle’s daughter Rosemary, who was aggrieved at thye time with the ‘one dimensional’ characterisation she believed the author had painted of her late father. This was an unfortunate response as Levinson himself concedes that his book could not have been written without her invaluable assistance, a point he duly notes in the ‘acknowledgement’ section.

The biography opens with a musician’s recollection that Riddle never smiled. Rosemary is critical of Levinson’s book, saying that it sensationalized her father’s flaws without providing a full picture of his personality or his life. When asked what kind of father he was to her, Acerra immediately mentioned his sense of humour. “It’s what I miss,” she said.

Nelson Riddle: The Man Behind the Music (David Morrell) 2013

This groundbreaking study discusses Riddle’s remarkable career, analyzing the musical principles that made his arrangements so unmistakable and influential. At its core is the irony that a man whose music is described as “light” and “bright” should have been so bitter and disappointed in his life.

Comments

He was the master colorist of American popular music, an artful arranger who seamlessly blended Basie and Debussy, strings and saxophones, French horn, guitar, tiptoeing harps and tart muted trumpets.

Nelson Riddle framed the voices of Frank Sinatra, Ella Fitzgerald, Nat King Cole and others in suave, airy and swinging arrangements that cushioned and propelled them in fresh new ways. The classic records they made with Riddle in the 1950s, Sinatra’s “Songs for Swingin’ Lovers,” “In the Wee Small Hours”, “Only the Lonely,” and Ella Fitzgerald’s Gershwin songbook, all retain their sparkle and seductive beauty, yet the man himself is largely unknown by today’s youngsters, an undeserving fate for an arranger who understood the orchestra so well that he never overwrote anything. The master of understatement, Riddle was an extraordinarily sensitive and clever musician, the sheer verve of his writing and the varied palette of sonic textures masking an often troubled private life.

As the writer James Kaplan, notes in his book on Frank Sinatra:

“It is extraordinarily difficult, in the post–rock ’n’ roll, post-singer-songwriter, digitized world of modern popular music, to convey just how important a figure the arranger used to be. Of course orchestration was always essential to classical music, but in the early twentieth century, jazz and jazz-based popular music began in improvisation. Yet as the Jazz Age turned into the Swing Era, as the bands got bigger and the dance numbers got more elaborate, arrangements became ever more essential. And writing the tempi and harmonies and counterpoints in such a way as to match—or even deepen—the heart-quickening rush of improvised jazz was an art few men could master. Many of the early white big bands—like Paul Whiteman’s—were tootling, anodyne versions of more dynamic and artistically complex black organizations such as Duke Ellington’s and Jimmie Lunceford’s. This had less to do with the players—there was no shortage of great white instrumentalists—than with the men who were writing the charts. Tommy Dorsey’s band got a rocket boost in 1939 when Dorsey stole Lunceford’s great arranger Sy Oliver, and Oliver was still writing for Dorsey when Nelson Riddle joined Dorsey’s band five years later…”

As is often the case, with sublime creativity, Nelson Riddle was only a middling professional trombone player, skillful enough to play for the Charlie Spivak and Tommy Dorsey big bands at a young age (he joined Dorsey at twenty-three, in 1944, and held the third chair in the trombone section), yet immensely valued for his skills as an arranger. When Nelson Riddle set pencil to paper, magic happened. Unfortunately, he only ever received a flat fee for his arrangements and yet, compositionally, there is little doubting that they were mini masterpieces in their own right. His work with Sinatra, an aural marriage made in heaven, was instrumental in ‘nailing’ the definitive versions of many of the classic works from the American Songbook of the first half of the twentieth century. I have heard and own much of his recorded works and like all great artists, he has a signature sound.

\http://www.nelsonriddlemusic.com/\

By all accounts, he was not an assertive man. Self promotion requires a certain type of personality and to a degree, I can understand his reticence. For example, I am always reluctant to have a commendations section on my website for whilst I know I have satisfied customers who have requested family commissions and/or limited edition prints, I have also received the usual range of caustic feedback such as “My five year old can draw better than you mate!” It’s one of the reasons I was always uncomfortable with the US Tv show “This is your Life”, which transferred to the British ITV network in the mid 50’s and ran for decades. Over the course of 30 minutes, one sycophantic guest after another would be wheeled on to deliver a near religious epiphany; heaven only knows why a select band of subjects walked away from the proceedings when their secret was revealed – it must have been a form of revulsion at the unbalanced aspect to the entire programme rather than an intrinsic fear of any potential embarrassing revalations.

Nelson didn’t hire a publicist and his vast contribution to popular song was greatly ignored until Linda Ronstadt commissioned him to arrange a series of best selling torch albums in the mid 80’s. Tellingly, when the idea for engaging Riddle’s services was originally floated, the singer had no idea whether her preferred choice was still alive, so disengaged from the music industry had he been throughout the 70’s. A four day spell under contract to Muzack, Inc in 1980, re-recording forty of his all time favourite arrangements for use in elavators (lifts in Britain), was undoubtedly the nadir of his career. His contemporaries (Sinatra, Bennett, Williams etc), were still filling concert halls but they were singularly failing to attract a new younger audience. Suddenly, Riddle floored his musical accelerator, found an empathetic collaborator in the beguiling Ronstadt and had a three million bestseller on his hands. Hot to trot, two more collaborations would follow in addition to sold out appearances with the singer. Suddenly, the baby boomers had their eyes opened to the the works of George and Ira Gershwin, Cole Porter and Irving Berlin, the bewitching sound of Linda’s voice floating mesmerisingly over Nelson’s romantic arrangements. Produced by Ronstadt’s longtime collaborator Peter Asher, “What’s New” shimmered as a listening experience, being the first album to benefit from the latest Pure Analog 32-bit resolution technology for pure analog sound.