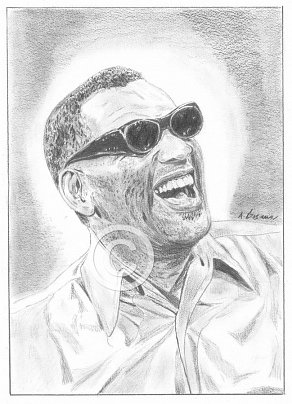

Ray Charles

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

The genius of Ray Charles (1959)

Ray’s Atlantic swansong and a powerhouse release. Having spent the Fifties working hard to pioneer his own sound, fusing jazz, gospel and the blues into the new soul style that reshaped American music, here Brother Ray relaxes for some mainly easy-swinging pop, with big-band arrangements.

Ray’s small combo is joined by members of the Duke Ellington and Count Basie’s bands, with the horn-heavy arrangements handled by close friend and collaborator, Quincy Jones.

The Genius hits the road (1960)

Eschewing self penned numbers, an overriding characteristic of his ABC-Paramount catalogue, Charles works a formula for alternating tearjerking ballads (the unforgettable version of “Georgia On My Mind” was a US #1 single), with lively big band work (“Alabamy Bound”), all tied together with a loose, lighthearted concept. The conceptual thread here is a homage to different locations in the United States; the rousing ‘Mississippi Mud,’ the tender ‘Moonlight In Vermont’ and the swinging ‘New York’s My Home,’ the last number composed by erzatz Sinatra conductor Gordon Jenkins. The urgency of Ray’s delivery makes the oldest chestnuts sound fresh (‘Chattanooga Choo-Choo’, ‘Basin Street Blues’), the arrangements bristle (“Moon Over Miami”), and there’s humour on ‘Deep in the heart of Texas,’ replete with an amusing spoken straight-man routine. The Genius was up and running leaving the marginalised Raelettes to look on despairingly, their future progressively consigned to life on the road rather than the studio.

Dedicated to you (1961)

A wonderful album, dedicated to twelve name-checked ladies.

The standout track “Ruby,” featuring a heart wrenching orchestral chart from guitarist Bill Fontaine, sits comfortably alongside a perfectly paced programme of big band and lush ballad arrangements.

The album was released in January 1961, and its sweeping instrumentation continued to bewilder fans of his early, sweaty R&B performances. Nevertheless, the intensity of Ray’s emotional performance will enrapture even the most casual of listeners, offering as it does, a window into the very soul of the man. The yearning “Stella by Starlight,” a comical “Hard Hearted Hanna,” and the effervescent “Margie” – a subsequent staple of Ray’s live act for the next few years – are further standouts.

An energetic “Sweet Georgia Brown” rounds off the proceedings, confirming “Dedicated To You” as one of his best ABC releases. If R & B and big production ballads weren’t enough, Brother Ray would place his label execs in a quandary only months later with a proposed move into the field of country music.

Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music (1962)

Wisely ignoring the advice of the ABC-Paramount A & R team, Brother Ray would persue his own musical vision, crafting one the top selling albums of the year. A sequel would soon be commissioned.

Extending the idea fashioned by Sinatra that an album could be peerceived as a cohesive art form – and not just a collection of singles and some filler – Charles would issue a sonic classic just around the time the 12-inch LP became the predominant listening format. Crushing racial barriers in the middle of the civil rights movement, this eclectic mix of revved up country-soul and string drenched ballads would join every corner of the music business together in a neat package, and made the well-known Ray Charles into a bonafide star. Just one listen to his souped up version of the Everley Brothers’ “Bye Bye love,” is enough to realise we’re into new musical territory. His biggest-selling record , it liberally applies gospel grit and luscious soul-pop strings to standards by Hank Williams and Eddy Arnold.

Remastered in 2005, I picked up my US import copy at the tail end of the year.

Modern Sounds in Country and Western Music Volume Two (1962)

Ingredients in a Recipe for Soul (1963)

Sweet & Sour Tears (1964)

A Portrait of Ray (1968)

A much maligned release, impeded in no small part by poor engineering and mastering. When I attempted to load my copy into the Brennan DB7 with 6x compression, the results on playback were poor to say the least, necessitating a repeat process with the facility switched off.

Sonic quibbles aside, I must take issue with the general reviews of this release, universally depicting an artist bereft of ideas after eight years with ABC Paramount. Some of the orchestral arrangements are pedestrian, but Brother Ray’s vocals are suitably arresting as the genius moves effortlessly from head voice to falsetto and back again. ‘Yesterdays’ stands proudly alongside the version on the ‘Sinatra and strings’ album whilst ‘The Sun Died’ is deftly handled, a beautiful treatise on an original french composition (Il Est Mort Le Soleil), remodelled with english lyrics. Best of all is ‘Eleanor Rigby,’ a version Lennon would cite as a personal favourite in his landmark ‘Rolling Stone’ interview in 1970.

The album is woefully light on original compositions – his one co-write is on the sexual stereotyping blues ‘Understanding,’ but ‘The Bright Lights and You Girl’ remains a particular favourite of mine, and worked well in a live setting, as footage from the Paris ’68 concert attests.

Live in Japan (1975)

The Spirit of Christmas (1985)

Recorded in 1985, ‘The Spirit of Christmas’ finds Ray Charles performing a variety of holiday favourites with vocal assistance from the Raelettes and an appearance by jazz trumpeter Freddie Hubbard. The ten tracks mix standards and originals, including “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town,” “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer,” and the ballad “That Spirit of Christmas,” which was featured in the movie ‘National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation.’ Hollywood took note and further song extracts from the album were lifted for use in blockbusters like “Die Hard 2” and “Elf.” It’s that unique combination of Ray’s R & B fingerprint, the blend of joy and ghetto jive in his vocalising and his trademark electro piano fills that transform standards into an all new listening experience.

There are a number of well known secular seasonal songs which receive his unique treatment; “Little Drummer Boy” uses a steel guitar and a horn section to support his bluesy lead vocal whilst “Rudolph The Red Nosed Reindeer” has a swinging jazzy feel which is far from Gene Autry’s original vision. He even manages to make the over recorded “Santa Claus Is Coming To Town” not only listenable, but actually very good.

He goes in a different direction with some lesser known songs; “Christmas Time” and “Christmas In My Heart” both returning him to his rhythm and blues vocal roots.

‘The Spirit Of Christmas,’ musically speaking, ranks alongside Presley’s ’57 yuletide release as one of the handful of classic seasonal offerings. My youngest daughter has it on her laptop and it plays every year whilst she assists her mother in the kitchen. I can’t remember the last time I consciously pulled it from the shelf and played it – she always beats me to the punch!

Recommended viewing

Ô-Genio: Live in Brazil ( 1963)

Despite the occasionally spotty video and audio quality, ‘Ô-Genio’ remains a long, lost treasure. When I purchased the original US DVD, I was fortunate to own a ‘chipped’ multi-region player, for so accustomed was I to seeing Ray, the elder statesman of R & B, that an opportunity to witness him in his prime was an unexpected delight. Normally, I would have been compelled to pass over this Region 1 purchasing opportunity but this time, it was in my possession within minutes of finding it.

Featuring an hour-long rehearsal as well as the complete concert that was broadcast live on Brazilian television, the program captures images of Ray Charles at an extraordinary peak in his career. With songs that ranged from his own ‘What’d I Say’ to Jimmie Davis’ country classic ‘You Are My Sunshine’ and from Bobby Timmons’ jazz gem ‘Moanin’to Percy Mayfield’s ‘Hit the Road Jack’, the footage beautifully highlights Charles’ eclectic ear, his exquisite vocal abilities, his unerring piano skills, and his talent for continually viewing familiar material from a fresh perspective. However, what is perhaps most astounding about the collection is the manner in which he took such disparate selections and unquestionably made them his own. After all, can anyone but Charles perform ‘You Are My Sunshine’ and the traditional ‘My Bonnie’ in the same show and make it sound anything but absurd? That he was just shy of 33 years of age is utterly miraculous, especially considering the emotional resonance that pours through his every utterance.

Backed by a 14-piece big band as well as the Raelettes, there was certainly no shortage of inspired moments, though his sparring with vocalist Margie Hendrix as well as his contributions on saxophone to an impromptu jam are among the finest on this remarkable set. It’s easy to cringe when something like ‘Ô-Genio: Live in Brazil, 1963’ surfaces so soon after an artist’s passing, but in this case, it was indeed a welcome addition to the Charles’ canon, one that uniquely spotlighted his otherworldly talent.

Ballad in Blue (1965)

Ray Charles plays himself in this film, in which he helps a blind boy David (Piers Bishop) in his struggle to regain his sight. David’s over-protective mother Peggy (Mary Peach) is afraid of the risks connected with restoring his sight whilst Ray tries to help the whole family, offering Peggy’s heavy-drinking partner Steve (Tom Bell) an opportunity to work with his band.

Some interesting background information on the movie can be located via the following link to the Ray Charles blog;

http://raycharlesvideomuseum.blogspot.co.uk/2010/03/ballad-in-blue-aka-blues-for-lovers.html

Comments

Last update: 20/11/2016

Shortly before Christmas 2002, Ray Charles called a meeting of his 12 children at a hotel near Los Angeles International Airport. They listened as their father told them he was mortally ill and outlined what they could expect from his fortune.

Most of Charles’ assets would be left to his charitable foundation. But $500,000 had been placed in trusts for each of the children to be paid out over the next five years, according to people at the meeting and a trust document. Yet Charles’ description left so much to the imagination that some of the children came away with the impression that he meant to leave them $1 million each. Charles also hinted that there would be more for them “down the line,” which some interpreted as future licensing rights to his name and likeness for profit.

The confusion and contention that resulted from the family gathering, essentially the only time so many of the children had met with their father as a group, set the tone for what was to come. Perhaps they should have expected little else from the man deservedly hailed as the ‘Genius of soul;’ ten of his children being conceived with an equivalent number of women. As he mentioned to Dick Cavett on his top rated chat show in 1972, he might have been blind but he still had the sense of touch and that was ‘far out’. The television audience laughed, seemingly oblivious to the reality of his private life, yet it is doubtful any of his twelve children would have been similarly amused.

At issue were not only money and the family’s standing but also the fate of thousands of musical recordings, videotapes and other artefacts produced during Charles’ long career. Professional estimates placed the value of Charles’ original masters at about $25 million, on top of the $50 million he held in securities, real estate and other assets.

Charles’ children were hoping to win control of the marketing of their father’s name and image, and a greater voice in foundation affairs.

“No one is as committed to Ray Charles as his family,” said Mary Anne Den Bok, an attorney who is the mother of Charles’ youngest child, Corey Robinson Den Bok.

The foundation, which Charles originally established as the Robinson Foundation for Hearing Disorders, had come under the scrutiny of the California attorney general’s office, which at one point objected to its control by a single executive, without an independent board.

The executive involved, Joe Adams, was the target of the family’s complaints. Adams, signed on as Charles’ manager in 1961. Toward the end of the artist’s life, he was perceived by Charles’ children and others close to him as controlling access to the star.

After Charles’ death, Adams ended up with virtually unchallenged power over the estate. He was head of Ray Charles Enterprises, director of the foundation and trustee of the children’s trusts. In some cases, co-officers appointed by Charles departed their roles while Adams remained.

Family members contend that Adams’ leadership has tarnished the image of the artist, who was known for decades as the “Genius,” a title bestowed on him by Frank Sinatra. In a federal lawsuit filed by Den Bok in the name of her son and nine of his other siblings, it was contested that Adams’ actions, along with those of other executives of the estate, had “distorted and trivialized” the value of the Charles name.

His manager, then 86, declined requests for an interview whilst his spokesman, called the assertions “old, baseless allegations.”

The family blamed Adams for the release of two posthumous Ray Charles CDs that, in a departure from Charles’ usual practice, were remixed from work he left behind and overdubbed with tracks by other singers. Both were commercial disappointments, even though they were released after the 2004 Oscar-winning biopic “Ray” had increased interest in Charles’ music.

The children had been unable to obtain an accounting of the estate, in part because their legal right to the information was unclear. Adams had kept the children and other family members from participating in ceremonies honouring their father, they said including his own funeral.

Adams interrupted a private family service at the Angelus Funeral Home in Los Angeles, attempted to eject some of the participants, and ordered the casket removed from the chapel, according to several people who were there.

Speaking at the time, the Rev. Robert Robinson, one of Charles’ sons, said in an interview : “The biggest issue with me is disrespect for the family and kids. If you respect a man and his work, then you respect his kids. His blood is flowing through our veins.”

Charles’ 12 children were widely dispersed with six registered in California, and one at least living abroad. Four were especially involved in controversies over the estate: Robert, 46; Ray Charles Jr., 52, whose mother, Della Robinson, was married to Charles from 1955 to 1977; and Raenee Robinson, 46, who was fighting a lawsuit filed by Adams over her right to market items bearing her father’s image. Whichever way anyone chose to look at it, the legacy of Ray Charles was in a mess.

Meanwhile Joe Adams, who’d been Ray Charles’ manager since 1961, didn’t receive anything in the will, yet he stayed in charge of all the business rights.

\http://www.sirshambling.com/artists_2012/H/margie_hendrix/index.php\

Although the young Ray began to lose his sight at the age of five, not long after witnessing his brother’s drowning, his eventual blindness by the age of seven was medical, not traumatic. Most medical experts agree glaucoma was the culprit, although growing up in Ray’s time and place, not to mention economic background, no one will ever be able to say for sure.

If glaucoma was at the root of Charles’s blindness, then it was probably of the chronic open-angle type that develops very slowly. By the age of seven, his condition was in an advanced state and in his search for light, he stared continuously at the sun thereby eliminating any chance for a future corneal transplant,

Born in Albany, Georgia, at the very beginning of the Great Depression, Ray shared his native town with the songwriter Hoagy Carmichael, who was already making his mark on the world. In 1930, the year of Ray’s birth, Hoagy recorded ‘Stardust,’ a song that became an all-time classic and the two men would eventually become inextricably entwined. In 1960, Ray Charles would be asked by the State of Georgia to perform, in the Georgia Legislative Chambers, its officially elected state song. The number was Ray’s version of Hoagy’s “Georgia on my mind,” and although Carmichael was too ill to attend the event, he listened in via a telephone/satellite tie-up.

The decade long ‘Great Depression’ had its roots in the Wall Street Crash of 1929. The initial crash occurred over several days, with Black Tuesday being the most devastating. That particular day, October 29, 1929, the market lost $14 billion, making the loss for that week an astounding $30 billion. This was ten times more than the annual federal budget and far more than the U.S. had spent in World war One. Thirty billion dollars would be equivalent to $377,587,032,770.41 today.

After the initial crash, there was a wave of suicides in the New York’s financial district. It is said that the clerks of one hotel even started asking new guests if they needed a room for sleeping or jumping.

The crash was precipitated by an “economic bubble,” a cycle characterized by rapid expansion with a subsequent contraction. In 1929, there was a surge in equity prices, unwarranted by their fundamentals. Effectively, these security prices were rising above their true value and would continue to do so until prices went into freefall thus bursting the bubble. By 1933, more than 11,000 of the nation’s 25,000 American banks had closed.

Turmoil would be the best word to describe 1930’s Georgia, and most of this upheaval occured right outside the farmhouse door. Beset by serious problems from 1920 onwards, the Great Depression only made the plight of the farmer worse. Falling cotton and tobacco prices, reductions in workforce thanks to the competition from cities, and poor land-use stratagies wrecked havoc on the sector that had supported the Georgia economy since the time of Oglethorpe. These three things combined to chase Georgians from the fields in record numbers. At the end of the ten-year period ending in 1940, less than one-third of all Georgia workers were employed in agriculture.

Economically, urban Georgians suffered less during the Great Depression than their counterparts to the North and West. One reason they had been insulated was the strong industrial base that had only recently begun to form. Coupled with low-cost labor and a dedicated workforce (remember, many had only recently come from farms and did not have the problems of workers in other parts of the country), large Georgia cities did as well as can be expected during this decade.

David Ritz, who co-authored Charles 1978 autobiography, has unequivocally stated, based on conversations with the musician, that Ray was brought up by ‘two mothers’, his biological mother, Aretha, and a woman named Mary Jane, one of his father’s former wives. “I called Aretha ‘Mama’ and Mary Jane ‘Mother,’ “ wrote Ray. After her 6-year-old son went blind, Aretha fostered his independence, while Mary Jane indulged him. For the rest of his life Ray was as fiercely self-reliant as he was self-indulgent. Two dynamic women, displaying two radically different approaches to his sightlessness, could not help but colour his character and temperament.

[Tour programme for Ray’s 1963 visit to Britain.]

https://www.flickr.com/photos/bradford_timeline/sets/72157628016538367/with/6350077919/