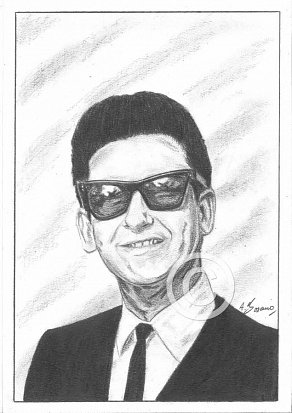

Roy Orbison

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended listening

The Essential Roy Orbison [Original Recording Remastered] (2 CD set) 2006

Any artist of Roy Orbison’s stature deserves a comprehensive, career-spanning compilation like Legacy’s 2006 double-disc ‘The Essential Roy Orbison.’ It may fall short of the mark in certain respects, yet it would be the first multi-disc Orbison compilation since 1988’s four-disc box ‘The Legendary Roy Orbison,’ which was released in the midst of his remarkable comeback, that would peak the following year with the posthumous comeback ‘Mystery Girl.’

Orbison’s catalog was therefore missing a set that spanned from “Ooby Dooby,” his first hit for Sun in 1956, all the way to his last charting single, 1992’s “I Drove All Night’” postumously produced by Jeff Lynne.

This set covers every phase of his career – the early rockabilly for Sun in the ’50s, his cinematic hits for Monument in the early ’60s, the cult classics for MGM in the late ’60s, his ’80s comeback – over the course of 40 tracks. There’s much to luxuriate in, particularly on the first disc, which has most of the big hits from “Ooby Dooby” to 1964’s “Oh, Pretty Woman,” all presented in chronological order.

Unfortunately, the chronological order goes awry on disc two, opening up with four choice cuts from ‘Mystery Girl’ (including the hits “You Got It” and “She’s a Mystery to Me”), before doubling back to the ’60s for five MGM singles – “Ride Away,” “Crawling Back,” “Best Friend,” “Communication Breakdown,” and “Walk On” – then proceeding to the ’80s, first with the Emmylou Harris duet_ “That Lovin’ You Feeling Again”_ from the Roadie soundtrack, and then with re-recordings of “Running Scared” and “In Dreams,” two ’60s masterworks that are only available here in these solid but inferior remakes. The jumbled chronology results in a bit of a disconcerting listen, since the production styles don’t comfortably sit together, but that would be easier to forgive if “Running Scared” and “In Dreams” were present in their original versions; without them, ‘Essential’ isn’t quite the concise, comprehensive collection it aspires to be. It’s a major flaw, but not necessarily a fatal one, since the remainder of the set does offer his biggest hits – “Only the Lonely (Know How I Feel),” “Candy Man,” “Crying,” “Dream Baby (How Long Must I Dream),” “Leah,” “Blue Bayou,” “It’s Over,” and “Pretty Paper” among them – plus a good sampling of his lesser-known work, all in good fidelity.

It’s easy to avoid quibbling but in all honesty, if record companies simply spent a little time liasing with the aficionados, then sheer aural perfection, chronologically presented, would always remain in touching distance.

Buy it, and then resequence the collection on your preferred hardware.

Mystery Girl (1989)

Orbison’s posthumous release, his first all-new collection of material in ten years, and a fitting valediction to the epic sweep and grandeur of his classic sound. Suitably swathed in meticulous, modern production values, the album encapsulates everything that made Orbison great, with a unified sound that belies the varied production credits. Despite the starry eyed supporting cast, George Harrison, Tom Petty, Jeff Lynne, Mitchell Froom, T Bone Burnett, Jim Keltner and members of Fleetwood Mac, it’s still Roy’s record, his spine-tingling bel-canto swells and swoops heightening the drama of even the most straightforward tune, from rockers like “You Got It” and “(All I Can Do Is) Dream You” to the schmaltzy balladry of “A Love So Beautiful.” The U2’ish Bono/Edge penned “She’s a Mystery to Me,” is a highlight of the collection, the Big O’s soaring register on the chorus underlying the thematic angst of the lyrical content.

If word association is the name of the Orbison game, lonely, dream and blue remain ever present yet Roy takes an unexpected turn with “In the Real World,” renouncing dreams and the self-pitying loneliness that pervades so much of his remarkable oeuvre. Best of all, there’s Elvis Costello’s tale of lost love, ‘The Comedians,’ a predictable theme with an odd spin, a reworking of a composition originally issued on his “Goodbye Cruel World” album in 1984. Conscious of his failure to nail his original vision, Costello revisited his earlier song for Orbison’s comeback, retaining only the chorus and melody, Roy’s pitch-perfect performance making the number entirely his.

A commercial success, the album’s lead off single ‘You Got It’, was Orbison’s last Top 40 hit, reaching #9 in April 1989; a fitting sign off and further testimony to Jeff Lynne’s production skills.

Recommended viewing

Black and white night (1987)

Orbison’s film noir, a monochrome extravaganza filmed at California’s Coconut Grove in Los Angeles 1986, featuring an all too short 56 minute set and a glittering array of star guests on varying duet and backup vocal duties. The Big O’s sartorial gaffe, a fringe buckskin leather jacket, is oddly out of synch with the black tie entertainers but his singing is peerless and the band rocks.

The set includes_ “Pretty Woman,” “Only the Lonely,” “Crying”_ and “Dream Baby,” and the star-studded group of friends – Jackson Browne, Elvis Costello, Bonnie Raitt, Bruce Springsteen, among others, join Orbison onstage in a 1940s nightclub setting.

The instrumental lynchpin is James Burton, former ‘house guitarist’ with the Elvis Presley band (1969-1977), who weaves his repertoire of chickin’ pickin’ fretwork throughout the proceedings.

A ‘must have’ addition to any serious music lover’s collection, and now available on Blue Ray for extra clarity of sound and vision.

Recommended reading

Orbison has not been well served by biographers in either the quality or quantity stakes. Ellis Amburn’s ‘Dark Star:The Tragic Story of Roy Orbison,’ is a rather pedestrian and mean spirited affair, the reminiscences of several original band members that Roy outgrew and left behind in Texas, all contributing to the image of a singularly focused man hell bent on a career. There is inevitably some validity in this characterisation, yet the recollections of his latter day band members attest to a clean living entertainer eschewing the booze, broads and drugs. Many of these musicians were on the road with him for more than twenty years and their memories remain warm.

Comments

Roy Orbison! What a beacon in the southernmost gloom. The amazing Roy Orbison. He was one of those Texan guys who could sail through anything, including his whole tragic life. His kids die in a fire, his wife dies in a car crash, nothing in his private life went right for the big O, but I can’t think of a gentler gentleman, or a more stoic personality. That incredible talent for blowing himself up from 5ft 6in to 6ft 9in, which he seemed to be able to do on stage. It was amazing to witness. He’s been in the sun, looking like a lobster, pair of shorts on. And we’re just sitting around playing guitars, having a chat, smoke and a drink. “Well, I’m on in five minutes.” We watch the opening number. And out walks this totally transformed thing that seems to have grown at least a foot with presence and command over the crowd. He was in his shorts just now; how did he do that? It’s one of those astounding things about working in the theatre. Backstage you can be a bunch of bums. And “Ladies and gentlemen” or “I present to you,” and you’re somebody else.

© Keith Richards 2010. Extracted from ‘Life’ by Keith Richards with James Fox, published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Falsetto, often translated as a “false voice,” is a vocal technique that allows male singers to perform notes ordinarily out of their natural range. Essentially, it pulls the male singer’s voice out of the chest and into the head, which is traditionally what helps female sopranos hit their highest notes. Some male singers only use falsetto to reach a few high notes before returning to their natural chest and throat voices, but a few can actually sing entire songs using this controlled technique.

The use of falsetto has been traced back to at least the Middle Ages, although early music theorists used the term almost interchangeably with “head voice.” Both men and women working in the field of opera were trained to use falsetto, although it was more common to hear trained male countertenors use it whenever female sopranos were either not available or else not permitted to perform. Male bass singers also used the technique sparingly when asked to perform notes in the high tenor range.

Nik Dirga wrote in a Roy Orbison CD review, “Roy Orbison was the voice of sorrow. But sorrow never sounded quite so sweet. For nearly 30 years, Orbison was the quintessential spokesman for the brokenhearted, with his trademark sunglasses, hiding his eyes, so all you would focus on was the voice.”

In many ways, his distinctive vocal technique compromised the commercial possibilities of his songwriting, his German widow Barbara, admitting on more than one occasion, that her late husband hated the fact that people wouldn’t cover his songs because his voice was so sacred. It seems there was an unwritten law that nobody could do justice to the Big O’s songs yet Roy wrote them and therefore as a writer, he hated the fact that other people wouldn’t touch them.

Orbison barely opened his mouth when he was singing, a vocal style characteristic of a strong ‘head voice’. The technique involves using the cavities inside the mouth to shape vocals. A head voice is very different to a chest voice, the big, loud voice that everybody sings with. Finding your head voice allows vocalists to slip between falsetto and that sweeter, soft sound that is just above it yet it’s not driven by the chest.

Yet there is a dramatic element to Orbison’s songs that is also tough to replicate. The emotion in Roy’s compositions is an element that people really want to feel, so delivering that sentiment remains a really big challenge when singers perform his songs for there’s an undertone of darkness and a mood to the material. He wrote pop songs, but they always went to another place. Sometimes there were minor changes – an unusual orchestral vignette, a change of pace, an harmonic shift, all serving to provide a little edge to the emotional resonance.

Interviewed extensively by Rolling Stone magazine in the months leading up to his death, Orbison reflected on the consistency of his vocalising throughout the years: ‘Yeah, I sound basically the same. When I was making my older records, I had more control over my vibrato — now, if I don’t want to have the vibrato in the studio, I have to do a session earlier in the day, because by the evening it’ll be there whether I want it or not. It’s a gift, and a blessing, just to have a voice. And I’m proud that people do appreciate it, you know? It’s a long way from being overwhelmed because you don’t know whether you’re worthy, to realizing that if you have a gift, it should be precious to you and you should look after it and respect it.’

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Roy_Orbison

Many people have assumed over the years that Roy Orbison was either blind or going blind and that is why he wore his trademark sunglasses. Although his glasses were prescription, he was not blind. It was at a show in England in the 1960’s that the singer realised he’d forgotten his regular glasses and the only pair he had with him was his sunglasses. He had no choice but to wear them. He liked the publicity shots that came from that show and decided thereafter to continue wearing the shades in his public life.

[Programme for Orbison’s March ’67 UK tour.]

https://www.flickr.com/photos/bradford_timeline/sets/72157651395419416

When I heard he’d died, it was another one of those incredulous moments, having given the Traveling Wilbury’s debut platter a spin on my turntable only an hour before the news broke. At last, after so many years in the commercial wilderness, his star was once again in the ascendancy – an all star collaborative project freshly issued and a new studio album slated for imminent release. Yet he did not die prematurely with groundbreaking music going with him to the grave. Nor did he die from his own excesses or cruel fate. He just passed away, his body old and tired and his impact on the culture long faded away, though some of his music remains timeless.

When I think of him today, I imagine a child, extremely shy, geeky, big-eared, bespectacled, and so light-skinned that he would be mistaken for an albino. From sources I have read, Orbison was ignored by his classmates to the point of feeling, as he remarked, ‘totally anonymous, even at home.’ By the age of 10, he was creating his own world where, armed with a guitar and an ethereal, tremulous voice, he slipped into dreams for solace. But what a voice and a near constant reminder that nobody “has it all”. He was blessed with an incomparable instrument and he touched millions of listeners with it.

http://www.icce.rug.nl/~soundscapes/VOLUME05/Roy_Orbison2.shtml

Roy Kelton Orbison was born in Vernon, Texas, on April 23rd, 1936. When he was six, his parents gave him a guitar; at eight, he showed up so often at auditions for a local radio show that they made him a regular. Orbison loved Lefty Frizzell, Frankie Laine’s pop hit “Jezebel,” the odd instrumental and, after the family moved to Wink, in West Texas, Mexican music and the rhythm & blues songs that would soon coalesce into rock & roll. In high school, Orbison led a band called the Wink Westerners, later renamed the Teen Kings. A few years later the group recorded “Ooby Dooby,” a nonsense rockabilly track written by some of Orbison’s college classmates, in a Dallas studio. That version wasn’t released, and neither was a version cut in Clovis, New Mexico, with future Buddy Holly producer Norman Petty. But Sun Records head Sam Phillips heard the song and invited the Teen Kings to his history-making studio in Memphis. They cut it one more time, and it became a minor hit.

A handful of rockabilly-style tunes followed; none were hits. All along, Orbison had wanted to sing ballads. He also wanted a better deal on his songwriting royalties, and when Nashville publisher Wesley Rose said he could get the Everly Brothers to record a tune Orbison had written for his college sweetheart and wife-to-be, Claudette, Orbison left Sun and, like Elvis Presley, signed with RCA. Unlike Elvis, he didn’t sell many records, and in 1959, after a pair of singles, he moved to producer Fred Foster’s label, Monument Records.

This time, everything clicked. Orbison’s third Monument single, “Only the Lonely,” began a string of lushly arranged, inventively structured pop ballads: “Running Scared,” for instance, was a rock & roll bolero that slowly built to a pitch of lover’s paranoia before its dramatic, happy ending.

In the early Sixties, the anguished grandeur of those songs was rivaled only by the work of producer Phil Spector and his stable of girl groups. From the Beatles to Bruce Springsteen, young rockers and young dreamers were listening to the sound of Roy Orbison, the heartbreaking balladeer — and, on tunes like “Oh, Pretty Woman” and “Working for the Man,” Roy Orbison, the rocker.

But Orbison’s momentum faded when he left Monument for a big-money deal with MGM Records in 1965. Subsequent producers, it seems, didn’t have the Fred Foster touch. The records were good but not great; a movie for MGM, a Civil War musical titled The Fastest Guitar Alive, didn’t do well.

In 1966 tragedy struck when Claudette Orbison was killed in a motorcycle accident, with Roy riding just ahead of her when it happened. He found it difficult to write any more songs, but he kept touring. Two years later, a fire destroyed his house in Hendersonville, Tennessee, killing two of his three children. From that point on, he refused to attend funerals.

The same year his first wife died, the signs of commercial decline were apparent, particularly in the United States. Whilst managing a top ten hit in Britain with ‘Too Soon To Know’, Orbison’s MGM recordings failed to reach the popularity of the Monument hits with which he is primarily identified. The quality of the MGM recordings are generally very good, and it was perhaps the changing nature of the music scene, rather than anything intrinsic to Orbison’s performances, that ensured his declining sales. Nevertheless, the extent of his career nosedive was unexpected, his popularity being essentially based on quality recorded output rather than superficial teen idol imagery. In Britain alone, the unexpected success of crooners like Englebert Humperdinck ensured a continuing demand for operatic ballads, a further perplexing aspect of Orbison’s commercial atrophy.

Recalling his work ethic after the deaths of his wife and sons, Orbison told Rolling Stone in late 1988: ‘Yeah, that had a definite impact. I remember going on a worldwide tour after… after both things happened. Sort of as therapy, but also to keep doing what I had been doing. If you’re trying to be true to yourself, and you would normally tour and write and function that way, if something traumatic happens to you, I’ve never seen the sense in dropping all that. Because it’s not necessarily a personal thing, you know? It happens directly to you, but it’s not directed at you, necessarily. In my case I went ahead and did what I normally did, insofar as I could, and then let love and time and things like that take care of everything. I guess I’m talking about faith, probably. And if you feel really singled out, I think you can make a lot of mistakes. I don’t know of anyone who hasn’t lost someone. This was something I knew by faith — but until the faith is strong enough, it does affect your work. That’s a process that took a while.’

Confessing to the understandably maudlin thoughts of ‘Why me?’ or ‘Why again?’ Orbison added: ‘You have that feeling, but what I was trying to convey is the faith that you have that this has a meaning and is to a purpose. It may be a mystery to you at the time, and is. But if the faith is there, you ask yourself, “What is it all about?” But not every day, every minute.

I feel that that’s what went on with me, you know? It was a long, long time ago, but I’m trying to reach back and really give you what went on as opposed to what I would like to have had happen. It was a devastating blow, but not debilitating. I wasn’t totally incapacitated by events. And I think that’s stood me in good stead. You don’t come out unscathed, but you don’t come out murdered, you know? And of course, I remarried in ’69, Barbara and I, and we started our life together. And in fact, we were carrying on a romance long-distance at the time of the fire. I don’t know whether she knows this, but she was a source of inspiration and faith too. So I have to give her credit’.

Orbison was clearly adhering to one of the primary rules of dealing with child bereavement; namely being gentle with himself. Without due care and attention, he would have been of no use to his surviving child. Reviewing his last interview, he was apparently conscious of the grieving process but dismissive of any temporary insanity. Equally, he found his own support network in his second wife Barbara.

In 1980, Orbison and Emmylou Harris won a Grammy for their duet “That Lovin’ You Feelin’ Again,” which was featured in the comedy film ‘Roadie’, in which he also cameoed, yet a full on commercial revival remained elusive. Within a year, he could be seen lip synching ‘Oh Pretty Woman’ in an episode of ‘The Dukes of Hazzard’, an artist seemingly consigned to the nostalgia circuit.

In the end, it was the daily grind of a rock’n‘roll lifestyle rather than the hedonistic excesses that killed Orbison; the constant travelling and stage performances, fitful rest periods and the proliferation of motorway service junk food – small wonder that he’d had triple-bypass surgery by his early fifties. At the end, he was enjoying a healthy diet, and periodic workouts with a qualified trainer but the damage was done.

After Roy’s death, the management of his musical legacy was overseen by his widow Barbara. Sadly, she would die at the premature age of sixty on December 6, 2011 in Los Angeles on what was the 23rd anniversary of her husband’s death. She had been diagnosed in April of that year with pancreatic cancer.

In addition to overseeing Orbison’s catalog and several reissues of his music since his death, Barbara Orbison was the head of Still Working Music, a Nashville music publisher that was awarded BMI’s Song of the Year in 2010 for Taylor Swift’s “You Belong With Me.”

Earlier, in 2011, she had given an interview to mark the release of ‘The Monument Singles Collection’, a multi-disc package of the original mono mixes of Orbison’s most successful releases. Speaking of her late husband, she revealed that he was a compulsive moviegoer and that his best quality was his power of observation. ‘He saw,’ she said. ‘In fact, his close friends would have told you that he probably should have been a director.’