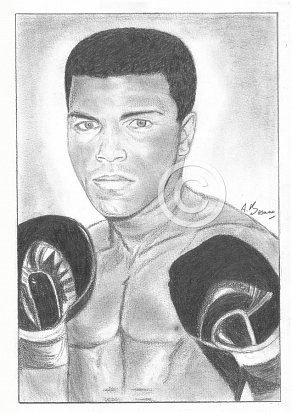

Muhammad Ali

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Ali v Zora Folley (1967)

http://boxrec.com/media/index.php/Muhammad_Ali_vs._Zora_Folley

The very zenith of Ali\‘s ring prowess and his 60’s swansong. What would follow – a three year exile and the loss of probably his peak fighting years – was a travesty. Whilst his draft refusal alienated middle America, he championed the rights of all his ‘brothers’ to reconsider their position in society, and the true identity of the ‘enemy within.’ None could be found in South East Asia.

The Vietnam War actually saw the highest proportion of blacks ever to serve in an American war. During the height of the U.S. involvement, 1965-69, blacks, who formed 11% of the American population, made up 12.6% of the soldiers in Vietnam. The majority of these were in the infantry, and although authorities differ on the figures, the percentage of black combat fatalities in that period was a staggering 14.9%, a proportion that subsequently declined. Volunteers and draftees included many frustrated blacks whose impatience with the war and the delays in racial progress in America led to race riots on a number of ships and military bases, beginning in 1968, and the services’ response in creating interracial councils and racial sensitivity training.

Facing almost as bitter a hostility from their fellow Americans as from the enemy, the subject of draft dodging can render me both ill with rage, and stupefied in equal measure that thousands more negroes didn’t follow in Ali’s footsteps. If America still treated them like fifth rate citizens, then by what right did it presume their unquestioning loyalty over a military conflict that still perplexed millions? As Ali so aptly put it: “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Viet Cong. No Viet Cong ever called me nigger.”

A superb resource detailing Ali\‘s humanitarian struggles can be located at:

http://www.aavw.org/protest/homepage_ali.html\

When we were kings (1996)

If Ali wasn’t afraid of George Foreman, then everyone else was, including myself. In those far flung days before he morphed into genial George with his big grill adverts, the World Champion was one mean SOB. Opponents who had troubled Ali greatly over 12/15 rounds had been despatched within minutes like a child swatting a fly. In Norman Mailer’s account, even Ali’s best jokes bore the hallmark of weakness, a buzzing, dispiriting counterpart to Foreman’s strong silence.

Yet Ali won, because he was fit and fast, and clearheaded enough to fight the way he wanted to. He was singularly focused throughout his training schedule, whilst rumours abounded of Foreman chasing scantily clad girls around his swimming pool.

What followed next is now part of boxing folklore.

In the eighth round Ali knocked Foreman down and Mailer, whose reporting in his book “The Fight,” is quick, intelligent and sympathetic throughout, describes Foreman\‘s descent from the championship in this way:

“Foreman’s arms flew out to the side like a man with a parachute jumping out of a plane, and in this doubled-over position he tried to wander out to the center of the ring. All the while his eyes were on Ali and he looked up with no anger as if Ali, indeed, was the man he knew best in the world and would see him on his dying day. Vertigo took George Foreman and revolved him. Still bowing from the waist in this uncomprehending position, eyes on Muhammad Ali all the way, he started to tumble and topple and fall even as he did not wish to go down. . . . He went over like a six-foot sixty-year-old butler who has just heard tragic news. . . .”

Whilst the fading champ received a full eight count, I’m unsure whether Ali would have survived the Foreman onslaught without recourse to his ‘rope a dope’ tactics, yet all this speculation misses the point. The result was a triumph against overwhelming odds, and vindication for the Louisville Lip’s canny intelligence, for Foreman was something else. A force of nature unlike anyone he had fought. Despite the crowd and the totally unexpected first round right hand lead combinations, the champ remained standing, forcing Ali to think of something else. Mailer was sitting ringside, and as the bell for the end of the first round sounded, he would describe the moment in “When we were kings”:

‘Ali went back to the corner………. Finally the nightmare he’d been awaiting in the ring had finally come to visit him. He was in the ring with a man he could not dominate, who was stronger than him, who was not afraid of him, who’d try to knock him out, and who punched harder than Ali, and this man was determined and unstoppable.

Ali had a look on his face that I’ll never forget. It was the only time I ever saw fear in Ali’s eyes. Ali looked as if he looked into himself and said, “All right, this is the moment. This is what you’ve been waiting for. This is…that hour. Do you have the guts?” And he kind of nodded, like, “Really got to get it together, boy. “You are gonna get it together… you WILL get it together.”

It’s great cinema and a fitting tribute to sport’s ultimate showman.

Ali (2001)

It’s all about perception. The acclaimed critic Roger Ebert wrote:

“Ali” is a long, flat, curiously muted film about the heavyweight champion. It lacks much of the flash, fire and humor of Muhammad Ali and is shot more in the tone of a eulogy than a celebration. There is little joy here. The film is long and plays longer, because it permits itself sequences that are drawn out to inexplicable lengths while hurrying past others that should have been dramatic high points. It feels like an unfinished rough cut that might play better after editing.

Ebert particularly singles out the training sequence set in Zaire, after Ali travels there for “The Rumble in the Jungle.” he writes ‘He begins his morning run, which takes him past a panorama of daily life. All very well. But he runs and runs and runs, long after any possible point has been made—and runs some more. This is the kind of extended scene you see in an early assembly of a film, before the heavy lifting has started in the editing room.’ The thing is, you see, I love the whole sequence. It’s one of the scenes I particularly wait for, a re-affirmation of how Ali energised Zaire’s townsfolk.

Under construction

I am Ali (2014)

I was attracted by two aspects to this DVD – the unbelievably low second hand price I was able to secure, and the unusual directorial slant taken by the production team. Where most retellings of Ali’s story concentrate on the man’s athletic and political exploits and relegate Ali the father and husband to the background, this one inverts the usual emphases. It is still, like most Ali documentaries, a hagiography, stepping gently around facts that aren’t flattering to the champ, such as his apparently chronic fidelity problems. Nevertheless, his third wife Veronica Porsche – and one of the film’s witnesses – confirms that she started dating Ali in 1974 when he was still married, and that he in turn, was not faithful to her. If not already, a consistent character trait – Ali would have been aware himself by his mid 30’s – that all was not well. Certainly, by 1976, I was noticing a slowing in his reflexes, and a somewhat slurred speech in his television interviews. Psychologically, his time to “make hay” was all too short. Clearly, the opportunity was grabbed with both hands. Clearly, whilst not condonable behaviour, his actions were understandable. Porsche herself, remained philosophical about his philandering.

“It was too much temptation for him, with women who threw themselves at him,” his third wife, Veronica Porsche, 60, tells PEOPLE. “It didn’t mean anything. He didn’t have affairs – he had one-night stands. I knew beyond a doubt there were no feelings involved. It was so obvious, It was easy to forgive him.”

Nevertheless, Ali’s philandering eventually “became too much,” and the two divorced in 1986, after nine years of marriage. Millions will have their opinion on his marriages and the reasons for their breakdown. Whatever the motivation, Veronica Porsche was spared the role of carer – or if Ali’s wealth negated such a ‘hands-on’ commitment – then as wife to an ailing man.

Much of the film is built snippets from 80 hours’ worth of audio tapes gifted from Ali to his daughter Hana, the seventh of his nine kids. Heard publicly for the first time, these tapes find Ali talking to family members and close friends about his life. We’re privy to some life-altering choices such as his 1979 decision to return to the ring. This was a fateful one—he performed poorly, for the most part, and suffered a lot of damage—and to be able to hear him discussing it on the phone with one of his daughters is at once elating and unnerving. Rather than cut to news footage or still photos, Lewins shows a sound meter, the levels flatlining and then jumping to life. It’s as if we’re seeing two people’s life forces up there, pulsing.

Recommended reading

The mammoth book of Muhammad Ali (edited by David West) 2012

The best collection of writings on ‘The Greatest’ – period.

Muhammad Ali - Through the eyes of the world (2001)

A literary tie-in with the 90 minute eponymous documentary, produced by Transworld International, this compendium of heartfelt reminiscences by celebrities, writers, fellow boxers, and commentators, paints a vivid, if somewhat sanitised picture of the man himself.

Muhammad Ali - The Glory Years (Felix Dennis & Don Atyeo) 2002

The ultimate Ali coffee table book, richly illustrated with an incisive text.

Voted Sports Personality of the Century in 1999, the Louisville Lip towered over his generation, both in the ring and out of it. First published in 1975, “The Glory Years” is based on exhaustive interviews with Ali’s friends, family and associates, and was extensively updated to bring his story into the 21st century. It revisits his fantastic reign and celebrates his life, both in the ring and out, with a stunning collection of photographs taken over the last fifty years. Some were published here for the first time ever, with a silver printing process that makes this book a truly unique volume and a fitting celebration of a glorious reign.

An expensive volume, I obtained my copy for the princely sum of £2.99, which made every one of those 288 pages sweeter than ever.

Comments

Last Update : 08/08/16

Elder abuse is “a single, or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust, which causes harm or distress to an older person.”

The abuse of elders by caretakers is a worldwide issue. In 2002, the work of the World Health Organization brought international attention to the issue of elder abuse. It’s an extremely sensitive issue and from time to time, brought more readily into focus when aspersions are cast in the direction of individuals looking after famous celebrities.

The last few years of Muhammad Ali’s life were shrouded in controversy. In 2012, his brother claimed that the 71-year-old boxing legend was being gravely mistreated by his wife because according to him, she was more interested in Ali’s money than his well-being. ‘I think [Lonnie] married my brother just for the money,’ Rahman Ali told the National Enquirer of his sister-in-law. ‘She talks to him bad. He doesn’t even get fed properly. The last time we were together [for a July gala in London honoring Ali], he was so dehydrated. You could tell from his lips.’ Rahman, who is younger than Muhammad by two years, said his brother was a ‘prisoner in his own home’.

Whatever the truth behind these allegations, it remained an uncomfortable thought reconciling such images with a man whose popular appeal extended way beyond the boundaries of his chosen sport.

I loved Ali as a sporting icon, and the more I observed people in certain quarters baying for his blood in the ring, the more I realised how spectacularly he had hoodwinked them. At the vanguard of the civil rights movement, he was once approached by the owner of an segregationist diner who informed him that ‘we don’t serve niggers here.’ Quick as a flash, Ali retorted ‘Well that’s good, ‘cos I don’t eat ‘em!’

It seemed for more than twenty years, that he was able to encapsulate the mood of the times, and to redicule those who would still subjugate his race with panache, style and humour. Asked by the Irish sports correspondent Cathol O’Shannon in 1971, what it was like to be a negro boy in the south, Ali retorted that black was nowadays, a more appropriate descriptive term, for the Chinese were named after China, Cubans after Cuba, Irish people after Irelamd, Indonesinas after Indonessia, Japanese after Japan etc but there was no country named Negro. With the Vietnam war still raging and mindful of the effect his draft refusal had made on his professional life only four years earlier, he elaborated further on the subject of black oppression;

‘The day after the war in Vietnam, the Vietcong will be more of a citizen than the American negro. So we might be the fiftieth or sixtieth class if you break it down. If we were just second class, we’d be alright’.

Ali continues to divide opinion even after his death at 74 from parkinson’s disease. Despite his battles in the cause of freedom for his fellow negroes, he had – by his late 20’s – re-invented himself as an unapologetic rascist. Appearing on the “Parkinson Show” in November 1971, he expressed views on racial integration that still resonates today. Whilst I believe he was misguided – as one of the thousand rattlesnakes in his example, I would wouldn’t I? – he nevertheless succinctly summarised the problem confronting his ‘brothers.’

“There are many white people who mean right, and in their hearts wanna do right. If 10,000 snakes were coming down that aisle now, and I had a door that I could shut, and in that 10,000, 1,000 meant right, 1,000 rattlesnakes didn’t want to bite me, I knew they were good… Should I let all these rattlesnakes come down, hoping that that thousand get together and form a shield? Or should I just close the door and stay safe?”

Ali remained opposed to racial integration in marriage, and in one way, it is unfortunate that the programme was given over solely to his guest appearance. If the BBC had been able to bring on Cleo Laine and Johnny Dankworth, “The Greatest” would have been compelled to face his entrenched views head on.

Allies are obviously appreciated and vital to stopping racial injustice, but Ali’s words are still a pretty powerful reminder of the reality of being black in America. It’s pretty amazing, if unfortunate, that over 40 years later his words still resonate.

In 1966, he defied the US government by refusing to fight in the Vietnam War. Ali had recently converted to Islam, joining Elijah Muhammad’s Nation of Islam, and subsequently changed his name from Cassius Clay which he called his “slave” name. It was in the name of his religion that Ali claimed conscientious objection. While he objected on religious grounds, Ali also brought up the continuing racial inequality in the US as reasons why he objected to the war. Of the many memorable quotes given by “the greatest” boxer, one particularly poignant one centres around this.“Why should they ask me to put on a uniform and go 10,000 miles from home and drop bombs and bullets on brown people in Vietnam while so-called Negro people in Louisville are treated like dogs and denied simple human rights?,” he said. In a letter to US army personnel, which was auctioned in 2015 by Heritage auctions, Ali claimed he should be “entitled to exemption on the grounds he was a minister of religion.”

Firstly, let us consider the facts of the case. As a world renowned sports personality, Ali would have been asked to participate in exhibition rounds some considerable distance from the main theatre of war. Any announcement of his death would have had a demoralising effect on US troop morale.