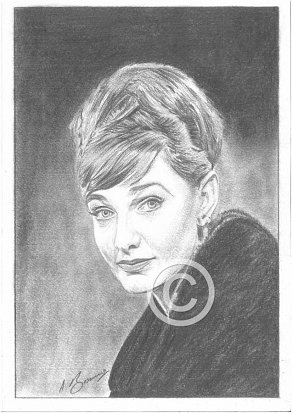

Barbara Murray

Pencil Portrait by Antonio Bosano.

Shopping Basket

The quality of the prints are at a much higher level compared to the image shown on the left.

Order

A3 Pencil Print-Price £45.00-Purchase

A4 Pencil Print-Price £30.00-Purchase

*Limited edition run of 250 prints only*

All Pencil Prints are printed on the finest Bockingford Somerset Velvet 255 gsm paper.

P&P is not included in the above prices.

Recommended viewing

Campbell's Kingdom (1957)

A Cry from the streets (1958)

Yes it’s dated, but this bittersweet and touching look at the life of a young welfare worker who cares for homeless and deprived young children in London and finds love with the cheery electrician who works at the children’s home, nevertheless remains a valued entry in director Lewis Gilbert’s oeuvre.

Based on the 1958 novel ‘A friend in need,’ by the author, critic and mountaineer Elizabeth Coxhead, the film largely concerns itself with three storylines; a trio of young siblings headed up by the self sufficient Barbie who become orphans when their father murders their mother during a drunken fight, Georgie, a young harmonica playing boy who believes his mother is a successful cabaret artiste touring the world rather than a drunk living just a few miles away, and an older boy, teenager Don, who is reunited and reconciled with his mother as he becomes a man in his own right.

Director Lewis Gilbert draws some marvellous performances from the juvenile cast, especially from the Australian child stars Colin Petersen (later to play drums for The Bee Gees) as Georgie, and Dana Wilson as Barbie. Wilson had found international stardom a year earlier for her role as the adorable Buster in the 1957 film, “The Shiralee,” which was filmed in Binnaway NSW. She would forsake acting in her teens, eventually marrying and raising a family of four. Sadly, she would die in 2015, at the rather premature age of 66. Here, as one of the cockney waifs, she may be unwashed but remains self-sufficiency itself. As the protectress of her two younger brothers, she bravely faces strange and terrifying grown-ups. Although she is child enough to cry on learning that her father had been hanged for murdering her mother, she also is ready to take charge and order her whimpering brothers to “shut up and go to sleep” in a perfectly mature style.

Some of the genuine location shots can be reviewed at:

Max Bygraves, combines the serious and light touches to make the role of the repairman a casually sensitive and pleasantly cheerful portrayal. As the pretty and dedicated social worker, who wins his heart as well as those of the children, Barbara Murray contributes a genuinely tender characterisation. She’s way too trusting of all and sundry, yet in many ways, it’s this unflinching belief in people that remains at the heart of her professional mojo.

There are, it might be added, brief but solid performances by Kathleen Harrison and Eleanor Summerfield, as the mothers of some of the youngsters, and by Mona Washbourne, as the officious head of the shelter. But they are only adults. “A Cry From the Streets” really belongs to its young fry.

Comments

An enticing presence, all misty eyes and pale beauty, Barbara Murray was the young Rank starlet who made a smooth and successful transition from decorative roles in films, to become a television and theatrical draw for two decades.

I used to love her characterisations onscreen – that sense of ‘regality,’ a palpable air of boredom in her domestic interraction with any male partner incapable of providing her with the affluent lifestyle she believed to be her divine right – yes, you’d find her attractive, interesting, amusing, but by God, you wouldn’t marry her.

Her looks seemed to strengthen in middle age, and there was a delicious mischievousness in her grand voice which ensured there was always more to the characters she played than just elegance and sophistication.

She made her biggest impact on television, in the British forerunner to Dallas, The Power Game (1965-69), in which she played Pamela, the bejewelled and fur-clad wife of the ruthless business executive John Wilder (played by Patrick Wymark). Murray took second billing to Wymark, ahead of the drama’s other stars, Michael Jayston, Jack Watling, Rosemary Leach and Peter Barkworth, and the Wilders’ private life – both had affairs – was as much a part of the drama as the high-powered business dealings.

The pair had first played the Wilders in The Plane Makers (1963-65), in which Wymark’s character was an aerospace tycoon battling with the unions on the shop floor. In The Power Game, he was transplanted to the boardroom of a merchant bank that takes control of a civil engineering company. He was also knighted, and his wife was seen revelling in the title of Lady Wilder. Only the death of Wymark brought The Power Game to an end.

Her earnings from this hugely popular programme enabled Murray to achieve her ambition of buying her own home, in Richmond upon Thames, Surrey. “I’ve been insecure, broke and unhappy, and having a house of my own always seemed the big unattainable,” she told TV Times in 1969. Earlier in the decade, she had appeared in two of my favourite episodes in the long running ITC series “The Saint,” alongside Roger Moore. In “The Good medicine,” (6/2/64) she plays Denise Dumont, the head one of the most successful beauty product firms in France and a very rich woman. However, she has achieved this by stealing the ideas of her ex-husband, Philippe whom she exploited, taking the credit for herself. He is now broken and ill. The Saint decides that, with the help of Denise’s former sister-in-law, he will teach this calculating woman a lesson and force her, unknowingly,to contribute to Philippe’s welfare. In one of the more light hearted entries in the series, the scheming Denise is fooled into believing our charming Mr Templar has patented a new odor free insect repellent. Unusually for the series, her appearance is considerably more than merely decorative, the actress enjoying considerable screen time without Mr Moore. In the earlier “Iris” (7/11/63) she plays the part of a racketeer’s beautiful actress wife, and is among those concerned in a scheme to involve Simon Templar in an ingenious blackmailing plot. Typical of many of her screen characters, she can overlook much of her husband’s repulsive ways in favour of the lifestyle he provides for her.

She was born in London, the daughter of a stage actor, Freddie Murray, and his wife, Petronella (nee Anderson). When Barbara was six, her mother and father teamed up in a variety dancing act, and she was sent to boarding school in Huntingdonshire. A quiet child, who enjoyed reading poetry and taking part in school plays, she would be evacuated to Wales with her mother after the Second World War. During this period, she briefly joined her parents on stage, but jobs were scarce and her father developed rheumatism, so she worked as a photographic model. Then, aged 17, Murray auditioned for the Rank Organisation’s talent-nurturing charm school and was offered a £10-a-week five-year contract. While training there, she had tiny parts in a string of films – starting with Anna Karenina (1948), which starred Vivien Leigh and Ralph Richardson, and including the Ealing Studios productions Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948) and Passport to Pimlico (1949), in which she played Stanley Holloway’s daughter – and acted in repertory theatre.

After marrying the actor John Justin in 1952, Murray was offered a new Rank contract but turned it down to spend more time at home with him and, later, to bring up their three daughters. “My best part is Mum,” she once said. However, Murray took stage roles that fitted in with family life, including her West End debut as Joanna Winter in No Other Verdict (Duchess theatre, 1954), shortly before the birth of her first child.

There were further London appearances as Isolde Poole in The Tunnel of Love (Her Majesty’s theatre, 1957-58, and Apollo, 1959) and with the Royal Shakespeare Company in the leading role of Stella in the original production of Harold Pinter’s The Collection (Aldwych, 1962), directed by Peter Hall. Murray’s only Broadway role, Madeline Hanes in the lingerie-business comedy In the Counting House (Biltmore theatre, 1962), ended with its cancellation after only six performances.

During this period, Murray returned to films, including “Campbell’s Kingdom” (1957, romancing Dirk Bogarde) and “The Punch and Judy Man” (1963), and had regular starring roles on television. In drama, she aged gracefully as the rich widow Madame Goesler (later Marie Finn) in The Pallisers (1974) and played Lydia, bickering matriarch of an acting dynasty, in The Bretts (1977-79). Doctor Who aficionados will recall her as Lady Cranleigh in the 1982 story Black Orchid. A rare film role during this time cast Murray as Ammonia, wife of Ludicrus Sextus (Michael Hordern), seen up to her neck in a milky bath, in Up Pompeii (1971).

In 1976, she spent six weeks in hospital after breaking her jaw when a car she was travelling in was involved in a collision during a British Council-sponsored acting tour of Brazil. “Fortunately, I was lucky and there were no marks on my face,” she reflected.

Murray retired from acting in 2001 and moved to Spain, following a national tour that year of “An Ideal Husband” with Hall’s company.